THE new guest's manner of presenting himself with his stick over his shoulder, and his carpet-bag on his back, subjected him to a battery of stares from Kenealy, Talboys, Fountain, and abashed him sore.

This lasted but a moment. He had one friend in the group who was too true to her flirtations while they endured, and too strong-willed, to let her flirtee be discouraged by mortal.

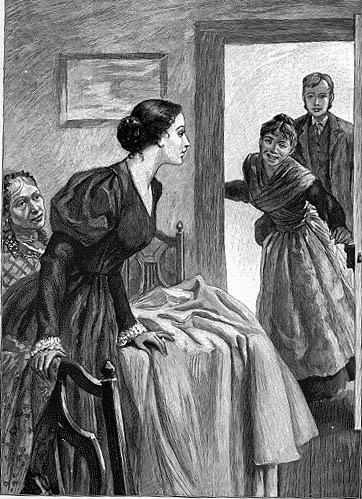

"Why, it is Mr. Dodd," cried she, with enthusiasm, and she put forth both hands to him, the palms downward, with a smiling grace. "Surely you know Mr. Dodd," said she, turning round quickly to the gentlemen, with a smile on her lip, but a dangerous devil in her eye.

The mistress of the house is all-powerful on these occasions. Messrs. Talboys and Fountain were forced to do the amiable, raging within; Lucy anticipated them; but her welcome was a cold one. Says Mrs. Bazalgette, tenderly, "And why do you carry that heavy bag, when you have that great stout lad with you? I think it is his business to carry it, not yours"; and her eyes scathed the boy, fiddle and all.

All the time she was saying this David was winking to her, and making faces to her not to go on that tack. His conduct now explained his pantomime. "Here, youngster," said he, "you take these things in-doors, and here is your half-crown."

Lucy averted her head, and smiled unobserved.

As soon as the lad was out of hearing, David continued: "It was not worth while to mortify him. The fact is, I hired him to carry it; but, bless you, the first mile he began to go down by the head, and would have foundered; so we shifted our cargoes." This amused Kenealy, who laughed good-humoredly. On this, David laughed for company.

"There," cried his inamorata, with rapture, "that is Mr. Dodd all over; thinks of everybody, high or low, before himself." There was a grunt somewhere behind her; her quick ear caught it; she turned round like a thing on a pivot, and slapped the nearest face. It happened to be Fountain's; so she continued with such a treacle smile, "Don't you remember, sir, how he used to teach your cub mathematics gratis?" The sweet smile and the keen contemporaneous scratch confounded Mr. Fountain for a second. As soon as he revived he said stiffly, "We can all appreciate Mr. Dodd."

Having thus established her Adonis on a satisfactory footing, she broke out all over graciousness again, and, smiling and chatting, led her guests beneath the hospitable roof.

But one of these guests did not respond to her cheerful strain. The Norman knight was full of bitterness. Mr. Talboys drew his friend aside and proposed to him to go back again. The senior was aghast. "Don't be so precipitate," was all that he could urge this time. "Confound the fellow! Yes, if that is the man she prefers to you, I will go home with you to-morrow, and the vile hussy shall never enter my doors again."

In this mind the pair went devious to their dressing-rooms.

One day a witty woman said of a man that "he played the politician about turnips and cabbages." That might be retorted (by a snob and brute) on her own sex in general, and upon Mrs. Bazalgette in particular. This sweet lady maneuvered on a carpet like Marlborough on the south of France. She was brimful of resources, and they all tended toward one sacred object, getting her own way. She could be imperious at a pinch and knock down opposition; but she liked far better to undermine it, dissolve it, or evade it. She was too much of a woman to run straight to her je-le-veux, so long as she could wind thitherward serpentinely and by detour. She could have said to Mr. Hardie, "You will take down Lucy to dinner," and to Mr. Dodd, "You will sit next me"; but no, she must mold her males--as per sample.

To Mr. Fountain she said, "Your friend, I hear, is of old family."

"Came in with the Conqueror, madam."

"Then he shall take me down: that will be the first step toward conquering me--ha! ha!" Fountain bowed, well pleased.

To Mr. Hardie she said, "Will you take down Lucy to-day? I see she enjoys your conversation. Observe how disinterested I am."

Hardie consented with twinkling composure.

Before dinner she caught Kenealy, drew him aside, and put on a long face. "I am afraid I must lose you to-day at dinner. Mr. Dodd is quite a stranger, and they all tell me I must put him at his ease.

"Yaas."

"Well, then, you had better get next Lucy, as you can't have me."

Yaas."

"And, Captain Kenealy, you are my aid-de-camp. It is a delightful post, you know, and rather a troublesome one."

"Yaas."

"You must help me be kind to this sailor."

"Yaas. He is a good fellaa. Carried the baeg for the little caed."

"Oh, did he?"

"And didn't maind been laughed at."

"Now, that shows how intelligent you must be," said the wily one; "the others could not comprehend the trait. Well, you and I must patronize him. Merit is always so dreadfully modest."

"Yaas."

This arrangement was admirable, but human; consequently, not without a flaw. Uncle Fountain was left to chance, like the flying atoms of Epicurus, and chance put him at Bazalgette's right hand save one. From this point his inquisitive eye commanded David Dodd and Mrs. Bazalgette, and raked Lucy and her neighbors, who were on the opposite side of the table. People who look, bent on seeing everything, generally see something; item, it is not always what they would like to see.

As they retired to rest for the night, Mr. Fountain invited his friend to his room.

"We shall not have to go home. I have got the key to our antagonist. Young Dodd is her lover." Talboys shook his head with cool contempt. "What I mean is that she has invited him for her own amusement, not her niece's. I never saw a woman throw herself at any man's head as she did at that sailor's all dinner. Her very husband saw it. He is a cool hand, that Bazalgette; he only grinned, and took wine with the sailor. He has seen a good many go the same road--soldiers, sailors, tinkers, tai--"

Talboys interrupted him. "I really must call you to order. You are prejudiced against poor Mrs. Bazalgette, and prejudice blinds everybody. Politeness required that she should show some attention to her neighbor, but her principal attention was certainly not bestowed on Mr. Dodd."

Fountain was surprised. "On whom, then?"

"Well, to tell the truth, on your humble servant."

Fountain stared. "I observed she did not neglect you; but when she turned to Dodd her face puckered itself into smiles like a bag."

"I did not see it, and I was nearer her than you," said Talboys coldly.

"But I was in front of her."

"Yes, a mile off." There being no jurisconsult present to explain to these two magistrates that if fifty people don't see a woman pucker her face like a bag, and one does see her p. h. f. l. a. b., the affirmative evidence preponderates, they were very near coming to a quarrel on this grave point. It was Fountain who made peace. He suddenly remembered that his friend had never been known to change an opinion. "Well," said he, "let us leave that; we shall have other opportunities of watching Dodd and her; meantime I am sorry I cannot convince you of my good news, for I have some bad to balance it. You have a rival, and he did not sit next Mrs. Bazalgette."

"Pray may I ask whom he did sit next?" sneered Talboys.

"He sat--like a man who meant to win--by the girl herself."

"Oh, then it is that sing-song captain you fear, sir?" drawled Talboys.

"No, sir, no more than I dread the épergne. Try the other side."

"What, Mr. Hardie? Why, he is a banker."

"And a rich one."

"She would never marry a banker."

"Perhaps not, if she were uninfluenced; but we are not at Talboys Court or Font Abbey now. We have fallen into a den of parvenues. That Hardie is a great catch, according to their views, and all Mrs. Bazalgette's influence with Lucy will be used in his favor.

"I think not. She spoke quite slightingly of him to me."

"Did she? Then that puts the matter quite beyond doubt. Why should she speak slightingly of him? Bazalgette spoke to me of him with grave veneration. He is handsome, well behaved, and the girl talked to him nineteen to the dozen. Mrs. Bazalgette could not be sincere in underrating him. She undervalued him to throw dust in your eyes."

"It is not so easy to throw dust in my eyes."

"I don't say it is; but this woman will do it; she is as artful as a fox. She hoodwinked even me for a moment. I really did not see through her feigned politeness in letting you take her down to dinner."

"You mistake her character entirely. She is coquettish, and not so well-bred as her niece, but artful she is not. In fact, there is almost a childish frankness about her."

At this stroke of observation Fountain burst out laughing bitterly.

Talboys turned pale with suppressed ire, and went on doggedly: "You are mistaken in every particular. Mrs. Bazalgette has no fixed views for her niece, and I by no means despair of winning her to my side. She is anything but discouraging."

Fountain groaned.

"Mr. Hardie is a new acquaintance, and Miss Fountain told me herself she preferred old friends to new. She looked quite conscious as she said it. In a word, Mr. Dodd is the only rival I have to fear--good-night;" and he went out with a stately wave of the hand, like royalty declining farther conference. Mr. Fountain sank into an armchair, and muttered feebly, "Good-night." There he sat collapsed till his friend's retiring steps were heard no more; then, springing wildly to his feet, he relieved his swelling mind with a long, loud, articulated roar of Anglo-Saxon, "Fool! dolt! coxcomb! noodle! puppy! ass!!!!"

Did ye ever read "Tully 'de Amicitia'?"

David Dodd was saved from misery by want of vanity. His reception at the gate by Miss Fountain was cool and constrained, but it did not wound him. For the last month life had been a blank to him. She was his sun. He saw her once more, and the bare sight filled him with life and joy. His was naturally a sanguine, contented mind. Some lovers equally ardent would have seen more to repine at than to enjoy in the whole situation; not so David. She sat between Kenealy and Hardie, but her presence filled the whole room, and he who loved her better than any other had the best right to be happy in the place that held her. He had only to turn his eyes, and he could see her. What a blessing, after a month of vacancy and darkness. This simple idolatry made him so happy that his heart overflowed on all within reach. He gave Mrs. Bazalgette answers full of kindness and arch gayety combined. He charmed an old married lady on his right. His was the gay, the merry end of the table, and others wished themselves up at it.

After the ladies had retired, his narrative powers, bonhomie and manly frankness soon told upon the men, and peals of genuine laughter echoed up to the very drawing-room, bringing a deputation from the kitchen to the keyhole, and irritating the ladies overhead, who sat trickling faint monosyllables about their three little topics.

Lucy took it philosophically. "Now those are the good creatures that are said to be so unhappy without us. It was a weight off their minds when the door closed on our retiring forms--ha! ha!"

"It was a restraint taken off them, my dear," said Mrs. Mordan, a starched dowager, stiffening to the naked eye as she spoke. "When they laugh like that, they are always saying something improper."

"Oh, the wicked things," replied Lucy, mighty calmly.

"I wish I knew what they are saying," said eagerly another young lady; then added, "Oh!" and blushed, observing her error mirrored in all eyes.

Lucy the Clement instructed her out of the depths of her own experience in impropriety. "They swear. That is what Mrs. Mordan means," and so to the piano with dignity.

Presently in came Messrs. Fountain and Talboys. Mrs. Bazalgette asked the former a little crossly how he could make up his mind to leave the gay party downstairs.

"Oh, it was only that fellow Dodd. The dog is certainly very amusing, but 'there's metal more attractive here.'"

Coffee and tea were fired down at the other gentlemen by way of hints; but Dodd prevailed over all, and it was nearly bedtime when they joined the ladies.

Mr. Talboys had an hour with Lucy, and no rival by to ruffle him.

Next day a riding-party was organized. Mr. Talboys decided in his mind that Kenealy was even less dangerous than Hardie, so lent him the quieter of his two nags, and rode a hot, rampageous brute, whose very name was Lucifer, so that will give you an idea. The grooms had driven him with a kicking-strap and two pair of reins, and even so were reluctant to drive him at all, but his steady companion had balanced him a bit. Lucy was to ride her old pony, and Mrs. Bazalgette the new. The horses came to the door; one of the grooms offered to put Lucy up. Talboys waved him loftily back, and then, strange as it may appear, David, for the first time in his life, saw a gentleman lift a lady into the saddle.

Lucy laid her right hand on the pommel and resigned her left foot; Mr. Talboys put his hand under that foot and heaved her smoothly into the saddle. "That is clever," thought simple David; "that chap has got more pith in his arm than one would think." They cantered away, and left him looking sadly after them. It seemed so hard that another man should have her sweet foot in his hand, should lift her whole glorious person, and smooth her sacred dress, and he stand by helpless; and then the indifference with which that man had done it all. To him it had been no sacred pleasure, no great privilege. A sense of loneliness struck chill on David as the clatter of her pony's hoofs died away. He was in the house; but in that house was a sort of inner circle, of which she was the center, and he was to be outside it altogether.

Liable to great wrath upon great occasions, he had little of that small irritability that goes with an egotistical mind and feminine fiber, so he merely hung his head, blamed nobody, and was sad in a manly way. While he leaned against the portico in this dejected mood, a little hand pulled his coat-tail. It was Master Reginald, who looked up in his face, and said timidly, "Will you play with me?" The fact is, Mr. Reginald's natural audacity had received a momentary check. He had just put this same question to Mr. Hardie in the library, and had been rejected with ignominy, and recommended to go out of doors for his own health and the comfort of such as desired peaceable study of British and foreign intelligence.

"That I will, my little gentleman," said David, "if I know the game."

"Oh, I don't care what it is, so that it is fun. What is your name?"

"David Dodd."

"Oh."

"And what is yours?"

"What, don't--you--know??? Why, Reginald George Bazalgette. I am seven. I am the eldest. I am to have more money than the others when papa dies, Jane says. I wonder when he will die."

"When he does you will lose his love, and that is worth more than his money; so you take my advice and love him dearly while you have got him."

"Oh, I like papa very well. He is good-natured all day long. Mamma is so ill-tempered till dinner, and then they won't let me dine with her; and then, as soon as mamma has begun to be good-tempered upstairs in the drawing-room, my bedtime comes directly; it's abominable!!" The last word rose into a squeak under his sense of wrong.

David smiled kindly: "So it seems we all have our troubles," said he.

"What! have you any troubles?" and Reginald opened his eyes in wonder. He thought size was an armor against care.

"Not so many as most folk, thank God, but I have some," and David sighed.

"Why, if I was as big as you, I'd have no troubles. I'd beat everybody that troubled me, and I would marry Lucy directly"; and at that beloved name my lord falls into a reverie ten seconds long.

David gave a start, and an ejaculation rose to his lips. He looked down with comical horror upon the little chubby imp who had divined his thought.

Mr. Reginald soon undeceived him. "She is to be my wife, you know. Don't you think she will make a capital one?" Before David could decide this point for him, the kaleidoscopic mind of the terrible infant had taken another turn. "Come into the stable-yard; I'll show you Tom," cried young master, enthusiastically. Finally, David had to make the boy a kite. When made it took two hours for the paste to dry; and as every ten minutes spent in waiting seemed an hour to one of Mr. Reginald's kidney, as the English classics phrase it, he was almost in a state of frenzy at last, and flew his new kite with yells. But after a bit he missed a familiar incident; "It doesn't tumble down; my other kites all tumble down."

"More shame for them," said David, with a dash of contempt, and explained to him that tumbling down is a flaw in a kite, just as foundering at sea is a vile habit in a ship, and that each of these descents, however picturesque to childhood's eye, implies a construction originally derective, or some little subsequent mismanagement. It appeared by Reginald's retort that when his kite tumbled he had the tumultuous joy of flying it again, but, by its keeping the air like this, monotony reigned; so he now proposed that his new friend should fasten the string to the pump-handle, and play at ball with him beneath the kite. The good-natured sailor consented, and thus the little voluptuary secured a terrestrial and ever-varying excitement, while occasional glances upward soothed him with the mild consciousness that there was his property still hovering in the empyrean; amid all which, poor love-sick David was seized with a desire to hear the name of her he loved, and her praise, even from these small lips. "So you are very fond of Miss Lucy?" said he.

"Yes," replied Reginald, dryly, and said no more; for it is a characteristic of the awfu' bairn to be mute where fluency is required, voluble where silence.

"I wonder why you love her so much," said David, cunningly. Reginald's face, instead of brightening with the spirit of explanation, became instantly lack-luster and dough-like; for, be it known, to the everlasting discredit of human nature, that his affection and matrimonial intentions, as they were no secret, so they were the butt of satire from grown-up persons of both sexes in the house, and of various social grades; down to the very gardener, all had had a fling at him. But soon his natural cordiality gained the better of that momentary reserve. "Well, I'll tell you," said he, "because you have behaved well all day."

David was all expectation.

"I like her because she has got red cheeks, and does whatever one asks her."

Oh, breadth of statement! Why was not David one of your repeaters? He would have gone and told Lucy. I should have liked her to know in what grand primitive colors peach-bloom and queenly courtesy strike what Mr. Tennyson is pleased to call "the deep mind of dauntless infancy." But David Dodd was not a reporter, and so I don't get my way; and how few of us do! not even Mr. Reginald, whose joyous companionship with David was now blighted by a footman. At sight of the coming plush, "There, now!" cried Reginald. He anticipated evil, for messages from the ruling powers were nearly always adverse to his joys. The footman came to say that his master would feel obliged if Mr. Dodd would step into his study a minute.

David went immediately.

"There, now!" squeaked Reginald, rising an octave. "I'm never happy for two hours together." This was true. He omitted to add, "Nor unhappy for one." The dear child sought comfort in retaliation. He took stones and pelted the footman's retiring calves. His admirers, if any, will be glad to learn that this act of intelligent retribution soothed his deep mind a little.

Mr. Bazalgette had been much interested by David's conversation the last night, and, hearing he was not with the riding-party, had a mind to chat with him. David found him in a magnificent study, lined with books, and hung with beautiful maps that lurked in mahogany cylinders attached to the wall; and you pulled them out by inserting a brass-hooked stick into their rings, and hauling. Mr. Bazalgette began by putting him a question about a distant port to which he had just sent out some goods. David gave him full information. Began, seaman-like, with the entrance to the harbor, and told him what danger his captain should look out for in running in, and how to avoid it; and from that went to the character of the natives, their tricks upon the sailors, their habits, tastes, and fancies, and, entering with intelligence into his companion's business, gave him some very shrewd hints as to the sort of cargo that would tempt them to sell the very rings out of their ears. Succeeding so well in this, Mr. Bazalgette plied him on other points, and found him full of valuable matter, and, by a rare union of qualities, very modest and very frank. "Now I like this," said Mr. Bazalgette, cheerfully. "This is a return to old customs. A century or two ago, you know, the merchant and the captain felt themselves parts of the same stick, and they used to sit and smoke together before a voyage, and sup together after one, and be always putting their heads together; but of late the stick has got so much longer, and so many knots between the handle and the point, that we have quite lost sight of one another. Here we merchants sit at home at ease, and send you fine fellows out among storms and waves, and think more of a bale of cotton spoiled than of a captain drowned."

David. "And we eat your bread, sir, as if it dropped from the clouds, and quite forget whose money and spirit of enterprise causes the ship to be laid on the stocks, and then built, and then rigged, and then launched, and then manned, and then sailed from port to port."

"Well, well, if you eat our bread, we eat your labor, your skill, your courage, and sometimes your lives, I am sorry to say. Merchants and captains ought really to be better acquainted."

"Well, sir," said David, "now you mention it, you are the first merchant of any consequence I ever had the advantage of talking with."

"The advantage is mutual, sir; you have given me one or two hints I could not have got from fifty merchants. I mean to coin you, Captain Dodd."

David laughed and blushed. "I doubt it will be but copper coin if you do. But I am not a captain; I am only first mate."

"You don't say so! Why, how comes that?"

"Well, sir, I went to sea very young, but I wasted a year or two in private ventures. When I say wasted, I picked up a heap of knowledge that I could not have gained on the China voyage, but it has lost me a little in length of standing; but, on the other hand, I have been very lucky; it is not every one that gets to be first mate at my age; and after next voyage, if I can only make a little bit of interest, I think I shall be a captain. No, sir, I wish I was a captain; I never wished it as now;" and David sighed deeply.

"Humph!" said Mr. Bazalgette, and took a note.

He then showed David his maps. David inspected them with almost boyish delight, and showed the merchant the courses of ships on Eastern and Western voyages, and explained the winds and currents that compelled them to go one road and return another, and in both cases to go so wonderfully out of what seems the track as they do. Bref, the two ends of the mercantile stick came nearer.

"My study is always open to you, Mr. Dodd, and I hope you will not let a day pass without obliging me by looking in upon me."

David thanked him, and went out innocently unconscious that he had performed an unparalleled feat. In the hall he met Captain Kenealy, who, having received orders to amuse him, invited him to play at billiards. David consented, out of good-nature, to please Kenealy. Thus the whole day passed, and les facheux would not let him get a word with Lucy.

At dinner he was separated from her, and so hotly and skillfully engaged by Mrs. Bazalgette that he had scarcely time to look at his idol. After dinner he had to contest her with Mr. Talboys and Mr. Hardie, the latter of whom he found a very able and sturdy antagonist. Mr. Hardie had also many advantages over him. First, the young lady was not the least shy of Mr. Hardie, but the parting scene beyond Royston had put her on her guard against David, and her instinct of defense made her reserved with him. Secondly, Mrs. Bazalgette was perpetually making diversions, whose double object was to get David to herself and leave Lucy to Mr. Hardie.

With all this David found, to his sorrow, that, though he now lived under the same roof with her, he was not so near her as at Font Abbey. There was a wall of etiquette and of rivals, and, as he now began to fear, of her own dislike between them. To read through that mighty transparent jewel, a female heart, Nauta had recourse--to what, do you think? To arithmetic. He set to work to count how many times she spoke to each of the party in the drawing-room, and he found that Mr. Hardie was at the head of the list, and he was at the bottom. That might be an accident; perhaps this was his black evening; so he counted her speeches the next evening. The result was the same. Droll statistics, but sad and convincing to the simple David. His spirits failed him; his aching heart turned cold. He withdrew from the gay circle, and sat sadly with a book of prints before him, and turned the leaves listlessly. In a pause of the conversation a sigh was heard in the corner. They all looked round, and saw David all by himself, turning over the leaves, but evidently not inspecting them.

A sort of flash of satirical curiosity went from eye to eye.

But tact abounded at one end of the room, if there was a dearth of it at the other.

La rusée sans le savoir made a sign to them all to take no notice; at the same time she whispered: "Going to sea in a few days for two years; the thought will return now and then." Having said this with a look at her aunt, that, Heaven knows how, gave the others the notion that it was to Mrs. Bazalgette she owed the solution of David's fit of sadness, she glided easily into indifferent topics. So then the others had a momentary feeling of pity for David. Miss Lucy noticed this out of the tail of her eye.

That night David went to bed thoroughly wretched. He could not sleep, so he got up and paced the deck of his room with a heavy heart. At last, in his despair, he said, "I'll fire signals of distress." So he sat down and took a sheet of paper, and fired: "Nothing has turned as I expected. She treats me like a stranger. I seem to drop astern instead of making any way. Here are three of us, I do believe, and all seem preferred to your poor brother; and, indeed, the only thing that gives me any hope is that she seems too kind to be in earnest, for it is not in her angelic nature to be really unkind; and what have I done? Eve, dear, such a change from what she was at Font Abbey, and that happy evening when she came and drank tea with us, and lighted our little garden up, and won your heart, that was always a little set against her. Now it is so different that I sit and ask myself whether all that is not a dream. Can anyone change so in one short month? I could not. But who knows? perhaps I do her wrong. You know I never could read her at home without your help, and, dear Eve, I miss you now from my side most sadly. Without you I seem to be adrift, without rudder or compass."

Then, as he could not sleep, he dressed himself, and went out at four o'clock in the morning. He roamed about with a heavy heart; at last he bethought him of his fiddle. Since Lucy's departure from Font Abbey this had been a great solace to him. It was at once a depository and vent to him; he poured out his heart to it and by it; sometimes he would fancy, while he played, that he was describing the beauties of her mind and person; at others, regretting the sad fate that separated him from her; or, hope reviving, would see her near him, and be telling her how he loved her; and, so great an inspirer is love, he had invented more than one clear melody during the last month, he who up to that time had been content to render the thoughts of others, like most fiddlers and composers.

So he said to himself, "I had better not play in the house, or I shall wake them out of their first sleep."

He brought out his violin, got among some trees near the stable-yard, and tried to soothe his sorrowful heart. He played sadly, sweetly and dreamingly. He bade the wooden shell tell all the world how lonely he was, only the magic shell told it so tenderly and tunefully that he soon ceased to be alone. The first arrival was on four legs: Pepper, a terrier with a taste for sounds. Pepper arrived cautiously, though in a state of profound curiosity, and, being too wise to trust at once to his ears, avenue of sense by which we are all so much oftener deceived than by any other, he first smelled the musician carefully and minutely all round. What he learned by this he and his Creator alone know, but apparently something reassuring; for, as soon as he had thoroughly snuffed his Orpheus, he took up a position exactly opposite him, sat up high on his tail, cocked his nose well into the air, and accompanied the violin with such vocal powers as Nature had bestowed on him. Nor did the sentiment lose anything, in intensity at all events, by the vocalist. If David's strains were plaintive, Pepper's were lugubrious; and what may seem extraordinary, so long as David played softly the Cerberus of the stableyard whined musically, and tolerably in tune; but when he played loud or fast poor Pepper got excited, and in his wild endeavors to equal the violin vented dismal and discordant howls at unpleasantly short intervals. All this attracted David's attention, and he soon found he could play upon Pepper as well as the fiddle, raising him and subduing him by turns; only, like the ocean, Pepper was not to be lulled back to his musical ripple quite so quickly as he could be lashed into howling frenzy.

While David was thus playing, and Pepper showing a fearful broadside of ivory teeth, and flinging up his nose and sympathizing loudly and with a long face, though not perhaps so deeply as he looked, suddenly rang behind David a chorus of human chuckles. David wheeled, and there were six young women's faces set in the foliage and laughing merrily. Though perfectly aware that David would look round, they seemed taken quite by surprise when he did look, and with military precision became instantly two files, for the four impudent ones ran behind the two modest ones, and there, by an innocent instinct, tied their cap-strings, which were previously floating loose, their custom ever in the early morning.

"Play us up something merry, sir," hazarded one of the mock-modest ones in the rear.

"Shan't I be taking you from your work?" objected David dryly.

"Oh, all work and no play is bad for the body," replied the minx, keeping ostentatiously out of sight.

Good-natured David played a merry tune in spite of his heart; and even at that disadvantage it was so spirit-stirring compared with anything the servants had heard, it made them all frisky, of which disposition Tom, the stable boy, who just then came into the yard, took advantage, and, leading out one of the housemaids by the polite process of hauling at her with both hands, proceeded to country dancing, in which the others soon demurely joined.

Now all this was wormwood to poor David; for to play merriment when the heart is too heavy to be cheered by it makes that heart bitter as well as sad. But the good-natured fellow said to himself: "Poor things, I dare say they work from morning till night, and seldom see pleasure but at a distance; why not put on a good face, and give them one merry hour." So he played horn-pipes and reels till all their hearts were on fire, and faces red, and eyes glittering, and legs aching, and he himself felt ready to burst out crying, and then he left off. As for il penseroso Pepper, he took this intrusion of merry music upon his sympathies very ill. He left singing, and barked furiously and incessantly at these ancient English melodies and at the dancers, and kept running from and running at the women's whirling gowns alternately, and lost his mental balance, and at last, having by a happier snap than usual torn off two feet of the under-housemaid's frock, shook and worried the fragment with insane snarls and gleaming eyes, and so zealously that his existence seemed to depend on its annihilation.

David gave those he had brightened a sad smile, and went hastily in-doors. He put his violin into its case, and sealed and directed his letter to Eve. He could not rest in-doors, so he roamed out again, but this time he took care to go on the lawn. Nobody would come there, he thought, to interrupt his melancholy. He was doomed to be disappointed in that respect. As he sat in the little summer-house with his head on the table, he suddenly heard an elastic step on the dry gravel. He started peevishly up and saw a lady walking briskly toward him: it was Miss Fountain.

She saw him at the same instant. She hesitated a single half-moment; then, as escape was impossible, resumed her course. David went bashfully to meet her.

"Good-morning, Mr. Dodd," said she, in the most easy, unembarrassed way imaginable.

He stammered a "good-morning," and flushed with pleasure and confusion.

He walked by her side in silence. She stole a look at him, and saw that, after the first blush at meeting her, he was pale and haggard. On this she dashed into singularly easy and cheerful conversation with him; told him that this morning walk was her custom--"My substitute for rouge, you know. I am always the first up in this languid house; but I must not boast before you, who, I dare say, turn out--is not that the word?--at daybreak. But, now I think of it, no! you would have crossed my hawse before, Mr. Dodd," using naval phrases to flatter him.

"It was my ill-luck; I always cruised a mile off. I had no idea this bit of gravel was your quarter-deck."

"It is, though, because it is always dry. You would not like a quarter-deck with that character, would you?"

"Oh yes, I should. I'd have my bowsprit always wet, and my quarter-deck always dry. But it is no use wishing for what we cannot have."

"That is very true," said Lucy, quietly.

David reflected on his own words, and sighed deeply.

This did not suit Lucy. She plied him with airy nothings, that no man can arrest and impress on paper; but the tone and smile made them pleasing, and then she asked his opinion of the other guests in such a way as implied she took some interest in his opinion of them, but mighty little in the people themselves. In short, she chatted with him like an old friend, and nothing more; but David was not subtle enough in general, nor just now calm enough, to see on what footing all this cordiality was offered him. His color came back, his eye brightened, happiness beamed on his face, and the lady saw it from under her lashes.

"How fortunate I fell in with you here! You are yourself again--on your quarter-deck. I scarce knew you the last few days. I was afraid I had offended you. You seemed to avoid me."

"Nonsense, Mr. Dodd; what is there about you to avoid?"

"Plenty, Miss Fountain; I am so inferior to your other friends."

"I was not aware of it, Mr. Dodd."

"And I have heard your sex has gusts of caprice, and I thought the cold wind was blowing upon me; and that did seem very sad, just when I am going out, and perhaps shall never see your sweet face or hear your lovely voice again."

"Don't say that, Mr. Dodd, or you will make me sad in earnest. Your prudence and courage, and a kind Providence, will carry you safe through this voyage, as they have through so many, and on your return the acquaintance you do me the honor to value so highly will await you--if it depends on me."

All this was said kindly and beautifully, and almost tenderly, but still with a certain majesty that forbade love-making--rendered it scarce possible, except to a fool. But David was not captious. He could not, like the philosopher, sift sunshine. For some days he had been almost separated from her. Now she was by his side. He adored her so that he could no longer realize sorrow or disappointment to come. They were uncertain--future. The light of her eyes, and voice, and face, and noble presence were here; he basked in them.

He told her not to mind a word he had said. "It was all nonsense. I am happier now--happier than ever."

At this Lucy looked grave and became silent.

David, to amuse her, told her there was "a singing dog aboard," and would she like to hear him?

This was a happy diversion for Lucy. She assented gayly. David ran for his fiddle, and then for Pepper. Pepper wagged his tail, but, strong as his musical taste was, would not follow the fiddle. But at this juncture Master Reginald dawned on the stable-yard with a huge slice of bread and butter. Pepper followed him. So the party came on the lawn and joined Lucy. Then David played on the violin, and Pepper performed exactly as hereinbefore related. Lucy laughed merrily, and Reginald shrieked with delight, for the vocal terrier was mortal droll.

"But, setting Pepper aside, that is a very sweet air you are playing now, Mr. Dodd. It is full of soul and feeling."

"Is it?" said David, looking wonderstruck; "you know best."

"Who is the composer?"

David looked confused and said, "No one of any note."

Lucy shot a glance at him, keen as lightning. What with David's simplicity and her own remarkable talent for reading faces, his countenance was a book to her, wide open, Bible print. "The composer's name is Mr. Dodd," said she, quietly.

"I little thought you would be satisfied with it," replied David, obliquely.

"Then you doubted my judgment as well as your own talent."

"My talent! I should never have composed an air that would bear playing but for one thing."

"And what was that?" said Lucy, affecting vast curiosity. She felt herself on safe ground now--the fine arts.

"You remember when you went away from Font Abbey, and left us all so heavy-hearted?"

"I remember leaving Font Abbey," replied Lucy, with saucy emphasis, and an air of lofty disbelief in the other incident.

"Well, I used to get my fiddle, and think of you so far away, and sweet sad airs came to my heart, and from my heart they passed into the fiddle. Now and then one seemed more worthy of you than the rest were, and then I kept that one."

"You mean you took the notes down," said Lucy coldly.

"Oh no, there was no need; I wrote it in my head and in my heart. May I play you another of your tunes? I call them your tunes."

Lucy blushed faintly, and fixed her eyes on the ground. She gave a slight signal of assent, and David played a melody.

"It is very beautiful," said she in a low voice. "Play it again. Can you play it as we walk?"

"Oh yes." He played it again. They drew near the hall door. She looked up a moment, and then demurely down again.

"Now will you be so good as to play the first one twice?" She listened with her eyelashes drooping. "Tweedle dee! tweedle dum! tweedle dee." "And now we will go into breakfast," cried Lucy, with sudden airy cheerfulness, and, almost with the word, she darted up the steps, and entered the house without even looking to see whether David followed or what became of him.

He stood gazing through the open door at her as she glided across the hall, swift and elastic, yet serpentine, and graceful and stately as Juno at nineteen.

These Junones, severe in youthful beauty, fill us Davids with irrational awe; but, the next moment, they are treated like small children by the very first matron they meet; they resign their judgment at once to hers, and bow their wills to her lightest word with a slavish meanness.

Creation's unmarried lords, realize your true position--girls govern you, and wives govern girls.

Mrs. Bazalgette, on Lucy's entrance, ran a critical eye over her, and scolded her like a six-year-old for walking in thin shoes.

"Only on the gravel, aunt," said the divine slave, submissively.

"No matter; it rained last night. I heard it patter. You want to be laid up, I suppose."

"I will put on thicker ones in future, dear aunt," murmured the celestial serf.

Now Mrs. Bazalgette did not really care a button whether the servile angel wore thick soles or thin. She was cross about something a mile off that. As soon as she had vented her ill humor on a sham cause, she could come to its real cause good-temperedly. "And, Lucy, love, do manage better about Mr. Dodd."

Lucy turned scarlet. Luckily, Mrs. Bazalgette was evading her niece's eye, so did not see her telltale cheek.

"He was quite thrown out last night; and really, as he does not ride with us, it is too bad to neglect him in-doors."

"Oh, excuse me, aunt, Mr. Dodd is your protégé. You did not even tell me you were going to invite him."

"I beg your pardon, that I certainly did. Poor fellow, he was out of spirits last night."

"Well, but, aunt, surely you can put an admirer in good spirits when you think proper," said Lucy slyly.

"Humph! I don't want to attract too much attention. I see Bazalgette watching me, and I don't wish to be misinterpreted myself, or give my husband pain."

She said this with such dignity that Lucy, who knew her regard for her husband, had much ado not to titter. But courtesy prevailed, and she said gravely: "I will do whatever you wish me, only give me a hint at the time; a look will do, you know."

The ladies separated; they met again at the breakfast-room door. Laughter rang merrily inside, and among the gayest voices was Mr. Dodd's. Lucy gave Mrs. Bazalgette an arch look. "Your patient seems better;" and they entered the room, where, sure enough, they found Mr. Dodd the life and soul of the assembled party.

"A letter from Mrs. Wilson, aunt."

"And, pray, who is Mrs. Wilson?"

"My nurse. She tells me 'it is five years since she has seen me, and she is wearying to see me.' What a droll expression, 'wearying.'"

"Ah!" said David Dodd.

"You have heard the word before, Mr. Dodd?"

"No, I can't say I have; but I know what it must mean."

"Lying becalmed at the equator, eh! Dodd?" said Bazalgette, misunderstanding him.

"Mrs. Wilson tells me she has taken a farm a few miles from this."

"Interesting intelligence," said Mrs. Bazalgette.

"And she says she is coming over to see me one of these days, aunt," said Lucy, with a droll expression, half arch, half rueful. She added timidly, "There is no objection to that, is there?"

"None whatever, if she does not make a practice of it; only mind, these old servants are the greatest pests on earth."

"I remember now," said Lucy thoughtfully, "Mrs. Wilson was always very fond of me. I cannot think why, though."

"No more can I," said Mr. Hardie, dryly; "she must be a thoroughly unreasonable woman."

Mr. Hardie said this with a good deal of grace and humor, and a laugh went round the table.

"I mean she only saw me at intervals of several years."

"Why, Lucy, what an antiquity you are making yourself," said Fountain.

But Lucy was occupied with her puzzle. "She calls me her nursling," said Lucy, sotto voce, to her aunt, but, of course, quite audibly to the rest of the company; "her dear nursling;" and says, "she would walk fifty miles to see me. Nursling? hum! there is another word I never heard, and I do not exactly know-- Then she says--"

"Taisez-vous, petite sotte!" said Mrs. Bazalgette, in a sharp whisper, so admirably projected that it was intelligible only to the ear it was meant for.

Lucy caught it and stopped short, and sat looking by main force calm and dignified, but scarlet, and in secret agony. "I have said something amiss," thought Lucy, and was truly wretched.

"We don't believe in Mrs. Wilson's affection on this side the table," said Mr. Hardie; "but her revelations interest us, for they prove that Miss Fountain had a beginning. Now we had thought she rose from the foam like Venus, or sprung from Jove's brow like Minerva, or descended from some ancient pedestal, flawless as the Parian itself."

"What, sir," cried Bazalgette, furiously, "did you think our niece was built in a day? So fair a structure, so accomplished a--"

"Will you be quiet, good people?" said Mrs. Bazalgette. "She was born, she was bred, she was brought up, in which I had a share, and she is a very good girl, if you gentlemen will be so good as not to spoil her for me with your flattery."

"There!" said Lucy, courageously, enforcing her aunt's thunderbolt; and she leaned toward Mrs. Bazalgette, and shot back a glance of defiance, with arching neck, at Mr. Bazalgette.

After breakfast she ran to Mrs. Bazalgette. "What was it?"

"Oh, nothing; only the gentlemen were beginning to grin."

"Oh, dear! did I say anything--ridiculous?"

"No, because I stopped you in time. Mind, Lucy, it is never safe to read letters out from people in that class of life; they talk about everything, and use words that are quite out of date. I stopped you because I know you are a simpleton, and so I could not tell what might pop out next."

"Oh, thank you, aunt--thank you," cried Lucy, warmly. "Then I did not expose myself, after all."

"No, no; you said nothing that might not be proclaimed at St. Paul's Cross--ha! ha!"

"Am I a simpleton, aunt?" inquired Lucy, in the tone of an indifferent person seeking knowledge.

"Not you," replied this oblivious lady. "You know a great deal more than most girls of your age. To be sure, girls that have been at a fashionable school generally manage to learn one or two things you have no idea of."

"Naturally."

"As you say--he! he! But you make up for it, my dear, in other respects. If the gentlemen take you for a pane of glass, why, all the better; meantime, shall I tell you your real character? I have only just discovered it myself."

"Oh, yes, aunt, tell me my character. I should so like to hear it from you."

"Should you?" said the other, a little satirically; "well, then, you are an INNOCENT FOX."

"Aunt!"

"An in-no-cent fox; so run and get your work-box. I want you to run up a tear in my flounce."

Lucy went thoughtfully for her workbox, murmuring ruefully, "I am an innocent fox--I am an in-nocent fox."

She did not like her new character at all; it mortified her, and seemed self-contradictory as well as derogatory.

On her return she could not help remonstrating: "How can that be my character? A fox is cunning, and I despise cunning; and I am sure I am not innocent," added she, putting up both hands and looking penitent. With all this, a shade of vexation was painted on her lovely cheeks as she appealed against her epigram.

Mrs. Bazalgette (with the calm, inexorable superiority of matron despotism). "You are an in-nocent fox!! Is your needle threaded? Here is the tear; no, not there. I caught against the flowerpot frame, and I'll swear I heard my gown go. Look lower down, dear. Don't give it up."

All which may perhaps remind the learned and sneering reader of another fox--the one that "had a wound, and he could not tell where."

They rode out to-day as usual, and David had the equivocal pleasure of seeing them go from the door.

Lucy was one of the first down, and put her hand on the saddle, and looked carelessly round for somebody to put her up. David stepped hastily forward, his heart beating, seized her foot, never waited for her to spring, but went to work at once, and with a powerful and sustained effort raised her slowly and carefully like a dead weight, and settled her in the saddle. His gripe hurt her foot. She bore it like a Spartan sooner than lose the amusement of his simplicity and enormous strength, so drolly and unnecessarily exerted. It cost her a little struggle not to laugh right out, but she turned her head away from him a moment and was quit for a spasm. Then she came round with a face all candor.

"Thank you, Mr. Dodd," said she, demurely; and her eyes danced in her head. Her foot felt encircled with an iron band, but she bore him not a grain of malice for that, and away she cantered, followed by his longing eyes.

David bore the separation well. "To-morrow morning I shall have her all to myself," said he. He played with Kenealy and Reginald, and chatted with Bazalgette. In the evening she was surrounded as usual, and he obtained only a small share of her attention. But the thought of the morrow consoled him. He alone knew that she walked before breakfast.

The next morning he rose early, and sauntered about till eight o'clock, and then he came on the lawn and waited for her. She did not come. He waited, and waited, and waited. She never came. His heart died within him. "She avoids me," said he; "it is not accident. I have driven her out of her very garden; she always walked here before breakfast (she said so) till I came and spoiled her walk; Heaven forgive me."

David could not flatter himself that this interruption of her acknowledged habit was accidental. On the other hand, how kind and cheerful she had been with him on the same spot yesterday morning. To judge by her manner, his company on her quarter-deck was not unwelcome to her yet she kept her room to-day, from the window of which she could probably see him walking to and fro, longing for her. The bitter disappointment was bad enough, but here tormenting perplexity as to its cause was added, and between the two the pining heart was racked.

This is the cruelest separation; mere distance is the mildest. Where land and sea alone lie between two loving hearts, they pine, but are at rest. A piece of paper, and a few lines traced by the hand that reads like a face, and the two sad hearts exult and embrace one another afresh, in spite of a hemisphere of dirt and salt water, that parts bodies but not minds. But to be close, yet kept aloof by red-hot iron and chilling ice, by rivals, by etiquette and cold indifference--to be near, yet far--this is to be apart--this, this is separation.

A gush of rage and bitterness foreign to his natural temper came over Mr. Dodd. "Since I can't have the girl I love, I will have nobody but my own thoughts. I cannot bear the others and their chat to-day. I will go and think of her, since that is all she will let me do"; and directly after breakfast David walked out on the downs and made by instinct for the sea. The wounded deer shunned the lively herd.

The ladies, as they sat in the drawing-room, received visits of a less flattering character than usual. Reginald kept popping in, inquiring, "Where was Mr. Dodd?" and would not believe they had not hid him somewhere. He was followed by Kenealy, who came in and put them but one question, "Where is Dawd?"

"We don't know," said Mrs. Bazalgette sharply; "we have not been intrusted with the care of Mr. Dodd."

Kenealy sauntered forth disconsolate. Finally Mr. Bazalgette put his head in, and surveyed the room keenly but in silence; so then his wife looked up, and asked him satirically if he did not want Mr. Dodd.

"Of course I do," was the gracious reply; "what else should I come here for?"

"Well, he is lost; you had better put him in the 'Hue and Cry.'"

La Bazalgette was getting jealous of her own flirtee: he attracted too much of that attention she loved so dear.

At last Reginald, despairing of Dodd, went in search of another playmate--Master Christmas, a young gentleman a year older than himself, who lived within half a mile. Before he went he inquired what there was for his dinner, and, being informed "roast mutton," was not enraptured; he then asked with greater solicitude what was the pudding, and, being told "rice," betrayed disgust and anger, as was remembered when too late.

At two o'clock, the day being fine, the ladies went for a long ride, accompanied by Talboys only. Kenealy excused himself: "He must see if he could not find Dawd."

Mrs. Bazalgette started in a pet; but, after the first canter, she set herself to bewitch Mr. Talboys, just to keep her hand in; she flattered him up hill and down dale. Lucy was silent and distraite.

"From that hill you look right down upon the sea," said Mrs. Bazalgette; "what do you say? It is only two miles farther."

On they cantered, and, leaving the high road, dived into a green lane which led them, by a gradual ascent, to Mariner's Folly on the summit of the cliff. Mariner's Folly looked at a distance like an enormous bush in the shape of a lion; but, when you came nearer, you saw it was three remarkably large blackthorn-trees planted together. As they approached it at a walk, Mrs. Bazalgette told Mr. Talboys its legend.

"These trees were planted a hundred and fifty years ago by a retired buccaneer."

"Aunt, now, it was only a lieutenant."

"Be quiet, Lucy, and don't spoil me; I call him a buccaneer. Some say it is named his 'Folly,' because, you must know, his ghost comes and sits here at times, and that is an absurd practice, shivering in the cold. Others more learned say it comes from a Latin word 'folio,' or some such thing, that means a leaf; the mariner's leafy screen." She then added with reckless levity, "I wonder whether we shall find Buckey on the other side, looking at the ships through a ghostly telescope--ha! ha!--ah! ah! help! mercy! forgive me! Oh, dear, it is only Mr. Dodd in his jacket--you frightened me so. Oh! oh! There--I am ill. Catch me, somebody;" and she dropped her whip, and, seeing David's eye was on her, subsided backward with considerable courage and trustfulness, and for the second time contrived to be in her flirtee's arms.

I wish my friend Aristotle had been there; I think he would have been pleased at her [Greek] (presence of mind) in turning even her terror of the supernatural so quickly to account, and making it subservient to flirtation.

David sat heart-stricken and hopeless, gazing at the sea. The hours passed by his heavy heart unheeded. The leafy screen deadened the light sound of the horses' feet on the turf, and, moreover, his senses were all turned inward. They were upon him, and he did not move, but still held his head in his hands and gazed upon the sea. At Mrs. Bazalgette's cries he started up, and looked confusedly at them all; but, when she did the feinting business, he thought she was going to faint, and caught her in his arms; and, holding her in them a moment as if she had been a child, he deposited her very gently in a sitting posture at the foot of one of the trees, and, taking her hand, slapped it to bring her to.

"Oh, don't! you hurt me," cried the lady in her natural voice.

Lucy, barbarous girl, never came to her aunt's assistance. At the first fright she seemed slightly agitated, but she now sat impassive on her pony, and even wore a satirical smile.

"Now, dear aunt, when you have done, Mr. Dodd will put you on your horse again."

On this hint David lifted her like a child, malgré a little squeak she thought it well to utter, and put her in the saddle again. She thanked him in a low, murmuring voice. She then plied David with a host of questions. "How came he so far from home?" "Why had he deserted them all day?" David hung his head, and did not answer. Lucy came to his relief: "It would be as well if you would make him promise to be at home in time for dinner; and, by the way, I have a favor to ask of you, Mr. Dodd."

"A favor to ask of me?!"

"Oh, you know we all make demands upon your good-nature in turn."

"That is true," said La Bazalgette, tenderly. "I don't know what will become of us all when he goes."

Lucy then explained "that the masked ball suggested by Mr. Talboys' beautiful dresses was to be very soon, and she wanted Mr. Dodd to practice quadrilles and waltzes with her; it will be so much better with the violin and piano than with a piano alone, and you are such an excellent timist--will you, Mr. Dodd?"

"That I will," said David, his eyes sparkling with delight; "thank you."

"Then, as I shall practice before the gentlemen join us, and it is four o'clock now, had you not better turn your back on the sea, and make the best of your way home?"

"I will be there almost as soon as you."

"Indeed! what, on foot, and we on horseback?"

"Ay; but I can steer in the wind's eye."

"Aunt, Mr. Dodd proposes a race home."

"With all my heart. How much start are we to give him?"

"None at all," said David; "are you ready? Then give way," and he started down the hill at a killing pace.

The equestrians were obliged to walk down the hill, and when they reached the bottom David was going as the crow flies across some meadows half a mile ahead. A good canter soon brought them on a line with him, but every now and then the turns of the road and the hills gave him an advantage. Lucy, naturally kind-hearted, would have relaxed her pace to make the race more equal, but Talboys urged her on; and as a horse is, after all, a faster animal than a sailor, they rode in at the front gate while David was still two fields off.

"Come," said Mrs. Bazalgette, regretfully, "we have beat him, poor fellow, but we won't go in till we see what has become of him."

As they loitered on the lawn, Henry the footman came out with a salver, and on it reposed a soiled note. Henry presented it with demure obsequiousness, then retired grinning furtively.

"What is this--a begging-letter? What a vile hand! Look, Lucy; did you ever? Why, it must be some pauper."

"Have a little mercy, aunt," said Lucy, piteously; "that hand has been formed under my care and daily superintendence: it is Reginald's."

"Oh, that alters the case. What can the dear child have to say to me! Ah! the little wretch! Send the servants after him in every direction. Oh, who would be a mother!"

The letter was written in lines with two pernicious defects. 1st. They were like the wooden part of a bow instead of its string. 2d. They yielded to gravity--kept tending down, down, to the righthand corner more and more. In the use of capitals the writer had taken the copyhead as his model. The style, however, was pithy, and in writing that is the first Christian grace--no, I forgot, it is the second; pellucidity is the first.

"Dear mama, me and johnny

Cristmas are gone to the north

Pole his unkle went twise we

Shall be back in siks munths

Please give my love to lucy and

Papa and ask lucy to be kind to

My ginnipigs i shall want them

Wen i come back. too much

Cabiges is not good for ginnipigs.

Wen i come back i hope there

Will be no rise left. it is very

Unjust to give me those nasty

Messy pudens i am not a child

There filthy there abbommanabel.

Johny says it is funy at the north

Pole and there are bares and they

Are wite.

"I remain

"Your duteful son

"Reginald George Bazalgette."

This innocent missive set house and premises in an uproar. Henry was sent east through the dirt, multa reluctantem, in white stockings. Tom galloped north. Mrs. Bazalgette sat in the hall, and did well-bred hysterics for Kenealy and Talboys. Lucy pinned up her habit, and ran to the boundary hedge on the bare chance of seeing the figures of the truants somewhere short of the horizon. Lo, and behold, there was David Dodd crossing the very nearest field and coming toward her, an urchin in each hand.

Lucy ran to meet them. "Oh, you dear naughty children, what a fright you have given us! Oh, Mr. Dodd, how good of you! Where did you find them?"

"Under that hedge, eating apples. They tell me they sailed for the North Pole this morning, but fell in with a pirate close under the land, so 'bout ship and came ashore again."

"A pirate, Mr. Dodd? Oh, I see, a beggar--a tramp."

"A deal worse than that, Miss Lucy. Now, youngster, why don't you spin your own yarn?"

"Yes, tell me, Reggy."

"Well, dear, when I had written to mamma, and Johnny had folded it--because I can write but I can't fold it, and he can fold it but he can't write it--we went to the North Pole, and we got a mile; and then we saw that nasty Newfoundland dog sitting in the road waiting to torment us. It is Farmer Johnson's, and it plays with us, and knocks us down, and licks us, and frightens us, and we hate it; so we came home."

"Ha! ha! good, prudent children. Oh, dear, you have had no dinner."

"Oh, yes we had, Lucy, such a nice one: we bought such a lot of apples of a woman. I never had a dinner all apples before; they always spoil them with mutton and things, and that nasty, nasty rice"

"Hear to that!" shouted David Dodd. "They have been dining upon varjese" (verjuice), "and them growing children. I shall take them into the kitchen, and put some cold beef into their little holds this minute, poor little lambs."

"Oh yes, do; and I will run and tell the good news." She ran across the lawn, and came into the hall red with innocent happiness and agitation. "They are found, aunt, they are found; don't cry. Mr. Dodd found them close by, They have had no dinner, so that good, kind Mr. Dodd is taking them into the kitchen. I will send Master Christmas home with a servant. Shall I bring you Reggy to kiss?"

"No, no; wicked little wretch, to frighten his poor mother! Whip him, somebody, and put him to bed."

In the evening, soon after the ladies had left the dining-room, the pianoforte was heard playing quadrilles in the drawing-room. David fidgeted on his seat a little, and presently rose and went for his violin, and joined Lucy in the drawing-room alone. Mrs. B. was trying on a dress. Between the tunes Lucy chatted with him as freely and kindly as ever. David was in heaven. When the gentlemen came up from the dining-room, his joy was interrupted, but not for long. The two musicians played with so much spirit, and the fiddle, in particular, was so hearty, that Mrs. Bazalgette proposed a little quiet dance on the carpet: and this drew the other men away from the piano, and left David and Lucy to themselves.

She stole a look more than once at his bright eyes and rich ruddy color, and asked herself, "Is that really the same face we found looking wan and haggard on the sea? I think I have put an end to that, at all events." The consciousness of this sort of power is secretly agreeable to all men and all women, whether they mean to abuse it or no. She smiled demurely at her mastery over this great heart, and said to herself, "One would think I was a witch." Later in the evening she eyed him again, and thought to herself, "If my company and a few friendly words can make him so happy, it does seem very hard I should select him to shun for the few days he has to pass in England now; but then, if I let him think--I don't know what to do with him. Poor Mr. Dodd."

Miss Fountain did not torment her bolder aspirants with alternate distance and familiarity. She rode out every fine day with Mr. Talboys, and was all affability. She sat next Mr. Hardie at dinner, and was all affability.

Narrative has its limits and, to relate in some sequence the honest sailor's tortures in love with a tactician, I have necessarily omitted concurrent incidents of a still tamer character; but the reader may, by the help of his own intelligence, gather their general results from the following dialogues, which took place on the afternoon and evening of the terrible infant's escapade.

Mrs. Bazalgette. "'Well, my dear friend, and how does this naughty girl of mine use you?"

Mr. Hardie. "As well as I could expect, and better than I deserve."

Mrs. B. "Then she must be cleverer than any girl that ever breathed. However, she does appreciate your conversation; she makes no secret of it."

Mr. H. "I have so little reason to complain of my reception that I will make my proposal to her this evening if you think proper."

Mrs. Bazalgette started, and glanced admiration on a man of eight thousand a year, who came to the point of points without being either cajoled or spurred thither; but she shook her head. "Prudence, my dear Mr. Hardie, prudence. Not just yet. You are making advances every day; and Lucy is an odd girl; with all her apparent tenderness, she is unimpressionable."

"That is only virgin modesty," said Hardie, dogmatically.

"Fiddlestick," replied Mrs. B., good-humoredly. "The greatest flirts I ever met with were virgins, as you call them. I tell you she is not disposed toward marriage as all other girls are until they have tasted its bitters."

Mr. H. "If I know anything of character, she will make a very loving wife."

Mrs. B. (sharply). "That means a nice little negro. Well, I think she might, when once caught; but she is not caught, and she is slippery, and, if you are in too great a hurry, she may fly off; but, above all, we have a dangerous rival in the house just now."

Mr. H. "What, that Mr. Talboys? I don't fear him. He is next door to a fool."

Mrs. B. "What of that? Fools are dangerous rivals for a lady's favor. We don't object to fools. It depends on the employment. There is one office we are apt to select them for."

Mr. H. "A husband, eh?" The lady nodded.

Mrs. B. "I meant to marry a fool in Bazalgette, but I found my mistake. The wretch had only feigned absurdity. He came out in his true colors directly."

Mr. H. "A man of sense, eh? The sinister hypocrite! He only wore the caps and bells to allure unguarded beauty, and doffed them when he donned the wedding-suit."

Mrs. B. "Yes. But these are reminiscences so sweet that I shall be glad to return from them to your little affair. Seriously, then, Mr. Talboys is not to be overlooked, for this reason: he is well backed."

"By whom?"

"By some one who has influence with Lucy--her nearest relation, Mr. Fountain."

"What! is he nearer to her than you are?"

"Certainly; and she is fond of him to infatuation. One day I did but hint that selfishness entered into his character (he is eaten up with it), and that he told fibs; Mr. Hardie, she turned round on me like a tigress--Oh, how she made me cry!"

The keen hand, Hardie, smiled satirically, and after a pause answered with consummate coolness: "I believe thus much, that she loves her uncle, and that his influence, exerted unscrupulously--"

"Which it will be. He may be strong enough to spoil us, even though he should not be able to carry his own point; now trust me, my dear friend, Lucy's preference is clearly for you, but I know the weakness of my own sex, and, above all, I know Lucy Fountain. A mouse can help a lion in a matter of small threads, too small for his nobler and grander wisdom to see. Let me be your mouse for once." The little woman caught the great man with the everlasting hook, and the discussion ended in "claw me and I will claw thee," and in the mutual self-complacency that follows that arrangement. Vide "Blackwood," passim.

Mr. H. "I really think she would accept me if I offered to-day; but I have so high an opinion of your sagacity and friendship for me, madam, that I will defer my judgment to yours. I must, however, make one condition, that you will not displace my plan without suggesting a distinct course of action for me to adopt in its place."

This smooth proposal, made quietly but with twinkling eye, would have shut the mouth of nine advisers in ten, but it found the Bazalgette prepared.

"Oh, the pleasure of having a man of ability to deal with!" cried she, with enthusiasm. "This is my advice, then: stay Mr. Fountain out. He must go in a day or two. His time is up, and I will drop a hint of fresh visitors expected. When he is gone, warm by degrees, and offer yourself either in person, or through Bazalgette, or me."

"In person, then, certainly. Of all foibles, employing another pair of eyes, another tongue, another person to make love for one is surely the silliest."

"I am quite of your opinion," cried the lady, with a hearty laugh.

Mr. Fountain. "So you are satisfied with the state of things?"

Mr. Talboys. "Yes, I think I have beaten the sailor out of the field."

"Well, but--this Hardie?"

"Hardie! a shopkeeper. I don't fear him."

"In that case, why not propose? I have been doing the preliminaries--sounding your praises."

Mr. Talboys (tyrannically). "I propose next Saturday."

Mr. Fountain. "Very well."

Talboys. "In the boat."

"In the boat? What boat? There's no boat."

"I have asked her to sail with me from ---- in a boat; there is a very nice little lugger-rigged one. I am having the seats padded and stuffed and lined, and an awning put up, and the boat painted white and gold."

"Bravo! Cleopatra's galley."

"I assure you she looks forward to it with pleasure; she guesses why I want to get her into that boat. She hesitated at first, but at last consented with a look--a conscious look; I can hardly describe it."

"There is no need," cried Fountain. "I know it; the jade turned all eyelashes."

"That is rather exaggerated, but still--"

"But still I have described it--to a hair. Ha! ha!"

Talboys (gravely). "Well, yes."

Mr. Talboys, I am bound to own, was accurate. During the last day or two Lucy had taken a turn; she had been bewitching; she had flattered him with tact, but deliciously; had consulted him as to which of his beautiful dresses she should wear at the masked ball, and, when pressed to have a sail in the boat he was fitting for her, she ended by giving a demure assent.

Chorus of male readers, "Oh, les femmes, les femmes!"

David Dodd had by nature a healthy as well as a high mind; but the fever and ague of an absorbing passion were telling on it. Like many a great heart before his day, his heart was tossed like a ship, and went up to heaven, and down again to despair, as a girl's humor shifted, or seemed to shift, for he forgot that there is such a thing as accident, and that her sex are even more under its dominion than ours. No; whatever she did must be spontaneous, voluntary, premeditated even, and her lightest word worth weighing, her lightest action worth anxious scrutiny as to its cause.

Still he had this about him that the peevish and puny lover has not. Her bare presence was joy to him. Even when she was surrounded by other figures, he saw and felt but the one; the rest were nothings. But when she went out of his sight, some bright illusion seemed to fade into cold and dark reality. Then it fell on him like a weighty, icy hammer, that in three days he must go to sea for two years, and that he was no nearer her heart now than he was at Font Abbey. Was he even as near?

So the next afternoon he thrust in before Talboys, and put Lucy on her horse by brute force, and griped her stout little boot, which she had slyly substituted for a shoe, and touched her glossy habit, and felt a thrill of bliss unspeakable at his momentary contact with her; but she was no sooner out of sight than a hollow ache seized the poor fellow, and he hung his head and sighed.

"I say, capting," said a voice in his ear. He looked up, and there stood Tom, the stable-boy, with both hands in his pockets. Tom was not there by his own proper movement, but was agent of Betsy, the under-housemaid.

Female servants scan the male guests pretty closely too, without seeming to do it, and judge them upon lamentably broad principles--youth, health, size, beauty, and good temper. Oh, the coarse-minded critics! Hence it befell that in their eyes, especially after the fiddle business, David was a king compared with his rivals.

"If I look at him too long, I shall eat him," said the cook-maid.

"He is a darling," said the upper housemaid.

Betsy aforesaid often opened a window to have a sly look at him, and on one of these occasions she inspected him from an upper story at her leisure. His manner drew her attention. She saw him mount Lucy, and eye her departing form sadly and wistfully. Betsy glowered and glowered, and hit the nail on the head, as people will do who are so absurd as to look with their own eyes, and draw their own conclusions instead of other people's. After this she took an opportunity, and said to Tom, with a satirical air, "How are you off for nags, your way?"

"Oh, we have got enough for our corn," replied Tom, on the defensive.

"It seems you can't find one for the captain among you."

"Will you give a kiss if I make you out a liar?"

"Sooner than break my arm. Come, you might, Tom. Now is it reasonable, him never to get a ride with her, and that useless lot prancing about with her all day long?"

"Why don't you ride with 'em, capting?"

"I have no horse."

"I have got a horse for you, sir--master's."

"That would be taking a liberty."

"Liberty, sir! no; master would be so pleased if you would but ride him. He told me so."

"Then saddle him, pray."

"I have a-saddled him. You had better come in the stable-yard, capting; then you can mount and follow; you will catch them before they reach the Downs." In another minute David was mounted.

"Do you ride short or long, capting?" inquired Tom, handling the stirrup-leather.

David wore a puzzled look. "I ride as long as I can stick on;" and he trotted out of the stable-yard. As Tom had predicted, he caught the party just as they went off the turn-pike on to the grass. His heart beat with joy; he cantered in among them. His horse was fresh, squeaked, and bucked at finding himself on grass and in company, and David announced his arrival by rolling in among their horses' feet with the reins tight grasped in his fist. The ladies screamed with terror. David got up laughing; his horse had hoped to canter away without him, and now stood facing him and pulling.

"No, ye don't," said David. "I held on to the tiller-ropes though I did go overboard." Then ensued a battle between David and his horse, the one wanting to mount, the other anxious to be unencumbered with sailors. It was settled by David making a vault and sitting on the animal's neck, on which the ladies screamed again, and Lucy, half whimpering, proposed to go home.

"Don't think of it," cried David. "I won't be beat by such a small craft as this--hallo!" for, the horse backing into Talboys, that gentleman gave him a clandestine cut, and he bolted, and, being a little hard-mouthed, would gallop in spite of the tiller-ropes. On came the other nags after him, all misbehaving more or less, so fine a thing is example. When they had galloped half a mile the ground began to rise, and David's horse relaxed his pace, whereon David whipped him industriously, and made him gallop again in spite of remonstrance.

The others drew the rein, and left him to gallop alone. Accordingly, he made the round of the hill and came back, his horse covered with lather and its tail trembling. "There," said he to Lucy, with an air of radiant self-satisfaction, "he clapped on sail without orders from quarter-deck, so I made him carry it till his bows were under water."

"You will kill my uncle's horse," was the reply, in a chilling tone.

"Heaven forbid!"

"Look at its poor flank beating."

David hung his head like a school-girl rebuked. "But why did he clap on sail if he could not carry it?" inquired he, ruefully, of his monitress.

The others burst out laughing; but Lucy remained grave and silent.

David rode along crestfallen.

Mrs. Bazalgette brought her pony close to him, and whispered, "Never mind that little cross-patch. She does not care a pin about the horse; you interrupted her flirtation, that is all."

This piece of consolation soothed David like a bunch of stinging-nettles.

While Mrs. Bazalgette was consoling David with thorns, Kenealy and Talboys were quizzing his figure on horseback.

He sat bent like a bow and visibly sticking on: item, he had no straps, and his trousers rucked up half-way to his knee.

Lucy's attention being slyly drawn to these phenomena by David's friend Talboys, she smiled politely, though somewhat constrainedly; but the gentlemen found it a source of infinite amusement during the whole ride, which, by the way, was not a very long one, for Miss Fountain soon expressed a wish to turn homeward. David felt guilty, he scarce knew why.

The promised happiness was wormwood. On dismounting, she went to the lawn to tend her flowers. David followed her, and said bitterly, "I am sorry I came to spoil your pleasure."

Miss Fountain made no answer.

"I thought I might have one ride with you, when others have so many."

"Why, of course, Mr. Dodd. If you like to expose yourself to ridicule, it is no affair of mine." The lady's manner was a happy mixture of frigidity and crossness. David stood benumbed, and Lucy, having emptied her flower-pot, glided indoors without taking any farther notice of him.

David stood rooted to the spot. Then he gave a heavy sigh, and went and leaned against one of the pillars of the portico, and everything seemed to swim before his eyes.

Presently he heard a female voice inquire, "Is Miss Lucy at home?" He looked, and there was a tall, strapping woman in conference with Henry. She had on a large bonnet with flaunting ribbons, and a bushy cap infuriated by red flowers. Henry's eye fell upon these embellishments: "Not at home," chanted he, sonorously.

"Eh, dear," said the woman sadly, "I have come a long way to see her."

"Not at home, ma'am," repeated Henry, like a vocal machine.

"My name is Wilson, young man," said she, persuasively, and the Amazon's voice was mellow and womanly, spite of her coal-scuttle full of field poppies. "I am her nurse, and I have not seen her this five years come Martinmas;" and the Amazon gave a gentle sigh of disappointment.

"Not at home, ma'am!" rang the inexorable Plush.

But David's good heart took the woman's part. "She is at home, now," said he, coming forward. "I saw her go into the house scarce a minute ago."

"Oh, thank you, sir," said Mrs. Wilson. But Mr. Plush's face was instantly puckered all over with signals, which David not comprehending, he said, "Can I say a word with you, sir?" and, drawing him on one side, objected, in an injured and piteous tone. "We are not at home to such gallimaufry as that; it is as much as my place is worth to denounce that there bonnet to our ladies."

"Bonnet be d--d," roared David, aloud. "It is her old nurse. Come, heave ahead;" and he pointed up the stairs.