AT the end of six months George Fielding's stock had varied thus. Four hundred lambs, ten calves, fifteen cows, four hundred sheep. He had lost some sheep in lambing, and one cow in calving, but these casualties every feeder counts on; he had been lucky on the whole. He had sold about eighty sheep, and eaten a few but not many, and of his hundred pounds only five pounds were gone; against which and the decline in cows were to be placed the calves and lambs.

George considered himself eighty pounds richer in substance than six months ago. It so happened that on every side of George but one were nomads, shepherd-kings--fellows with a thousand head of horned cattle, and sheep like white pebbles by the sea; but on his right hand was another small bucolical, a Scotchman, who had started with less means than himself, and was slowly working his way, making a halfpenny and saving a penny after the manner of his nation. These two were mighty dissimilar, but they were on a level as to means and near neighbors, and that drew them together. In particular, they used to pay each other friendly visits on Sunday evenings, and McLaughlan would read a good book to George, for he was strict in his observances; but after that the pair would argue points of husbandry.

But one Sunday that George, admiring his stock, inadvertently proposed to him an exchange of certain animals, he rebuked the young man with awful gravity.

"Is this a day for warldly dealings?" said he. "Hoo div ye think to thrive gien y'offer your mairchandeeze o' the Sabba day!" George colored up to the eyes. "Ye'll may be no hae read the paurable o' the money changers i' the temple, no forgettin' a wheen warldly-minded chields that sell't doos, when they had mair need to be on their knees--or hearkening a religious discourse---or a bit psaum--or the like. Aweel, ye need na hong your heed yon gate neether. Ye had na the privileege of being born in Scoetland, ye ken--or nae doot ye'd hae kenned better, for ye are a decent lad--deed are ye. Aweel, stap ben led, and I'se let ye see a drap whisky. The like does na aften gang doon an Englishman's thrapple."

"Whisky? Well, but it seems to me if we didn't ought to deal we didn't ought to drink."

"Hout! tout! it is no forbedden to taste--thaat's nae sen that ever I heerd't-- C-way."

GEORGE heard of a farmer who was selling off his sheep about fifty miles off near the coast. George put money in his purse, rose at three, and walked the fifty miles with Carlo that day. The next he chaffered with the farmer, but they did not quite agree. George was vexed, but he knew it would not do to show it, so he strolled away carelessly toward the water. In this place the sea comes several miles inland, not in one sheet, but in a series of salt-water lakes very pretty.

George stood and admired the water and the native blacks paddling along in boats of bark no bigger than a cocked hat. These strips of bark are good for carriage and bad for carriage; I mean they are very easily carried on a man's back ashore, but they won't carry a man on the water so well, and sitting in them is like balancing on a straw. These absurd vehicles have come down to these blockheads from their fathers, so they won't burn them and build according to reason. They commonly paddle in companies of three; so then whenever one is purled the other two come on each side of him, each takes a hand and with amazing skill and delicacy they reseat him in his cocked hat, which never sinks--only purls. Several of these triads passed in the middle of the lake, looking to George like inverted capital "T's." They went a tremendous pace--with occasional stoppages when a purl occurred.

Presently a single savage appeared nearer the land and George could see his lithe, sinewy form and the grace and rapidity with which he urged his gossamer bark along. It was like a hawk--half a dozen rapid strokes of his wings and then a smooth glide for ever so far.

"Our savages would sit on the blade of a knife, I do think," was George's observation.

Now as George looked and admired blackee, it unfortunately happened that a mosquito flew into blackee's nostrils, which were much larger and more inviting--to a gnat--than ours. The aboriginal sneezed, and over went the ancestral boat.

The next moment he was seen swimming and pushing his boat before him. He was scarce a hundred yards from the shore when all of a sudden down he went. George was frightened and took off his coat, and was unlacing his boots--when the black came up again. "Oh, he was only larking," thought George. "But he has left his boat--and why, there he goes down again!" The savage made a dive and came up ten yards nearer the shore, but he kept his face parallel to it, and he was scarce a moment in sight before he dived again. Then a horrible suspicion flashed across George--"There is something after him!"

This soon became a fearful certainty. Just before he dived next time, a dark object was plainly visible on the water close behind him. George was wild with fear for poor blackee. He shouted at the monster, he shouted and beckoned to the swimmer; and last, snatching up a stone, he darted up a little bed of rock elevated about a yard above the shore. The next dive the black came up within thirty yards of this very place, but the shark came at him the next moment. He dived again, but before the fish followed him George threw a stone with great precision and force at him. It struck the water close by him as he turned to follow his prey; George jumped down and got several more stones, and held one foot advanced and his arm high in air. Up came the savage panting for breath. The fish made a dart, George threw a stone; it struck him with such fury on the shoulders that it span off into the air and fell into the sea forty yards off. Down went the man, and the fish after him. The next time they came up, to George's dismay, the sea-tiger showed no signs of being hurt and the man was greatly distressed. The moment he was above water George heard him sob, and saw the whites of his eyes, as he rolled them despairingly; and he could not dive again for want of breath. Seeing this, the shark turned on his back, and came at him with his white belly visible and his treble row of teeth glistening in a mouth like a red grave.

Rage as well as fear seized George Fielding, the muscles started on his brawny arm as he held it aloft with a heavy stone in it. The black was so hard pressed the last time, and so dead beat, that he could make but a short duck under the fish's back and come out at his tail. The shark did not follow him this time, but cunning as well as ferocious slipped a yard or two inshore, and waited to grab him; not seeing him, he gave a slap with his tail-fin, and reared his huge head out of water a moment to look forth. Then George Fielding, grinding his teeth with fury, flung his heavy stone with tremendous force at the creature's cruel eye. The heavy stone missed the eye by an inch or two, but it struck the fish on the nose and teeth with a force that would have felled a bullock.

"Creesh!" went the sea-tiger's flesh and teeth, and the blood squirted in a circle. Down went the shark like a lump of lead, literally felled by the crashing stroke.

"I've hit him! I've hit him!" roared George, seizing another stone. "Come here, quick! quick! before he gets the better of it."

The black swam like a mad thing to George. George splashed into the water up to his knee, and taking blackee under the arm-pits, tore him out of the water and set him down high and dry.

"Give us your hand over it, old fellow," cried George, panting and trembling. "Oh dear, my heart is in my mouth, it is!"

The black's eye seemed to kindle a little at George's fire, but all the rest of him was as cool as a cucumber. He let George shake his hand and said quietly, "Thank you, sar! Jacky thank you a good deal!" he added in the same breath; "suppose you lend me a knife, then we eat a good deal."

George lent him his knife, and to his surprise the savage slipped into the water again. His object was soon revealed; the shark had come up to the surface and was floating motionless. It was with no small trepidation George saw this cool hand swim gently behind him and suddenly disappear; in a moment, however, the water was red all round, and the shark turned round on his belly. Jacky swam behind, and pushed him ashore. It proved to be a young fish about six feet long; but it was as much as the men could do to lift it. The creature's nose was battered, and Jacky showed this to George, and let him know that a blow on that part was deadly to them. "You make him dead for a little while," said he, "so then I make him dead enough to eat;" and he showed where he had driven the knife into him in three places.

Jacky's next proceeding was to get some dry sticks and wood, and prepare a fire, which to George's astonishment he lighted thus. He got a block of wood, in the middle of which he made a little hole; then he cut and pointed a long stick, and inserting the point into the block, worked it round between his palms for some time and with increasing rapidity. Presently there came a smell of burning wood, and soon after it burst into a flame at the point of contact. Jacky cut slices of shark and toasted them. "Black fellow stupid fellow--eat 'em raw; but I eat 'em burn't, like white man."

He then told George he had often been at Sydney, and could "speak the white man's language a good deal," and must on no account be confounded with common black fellows. He illustrated his civilization by eating the shark as it cooked; that is to say, as soon as the surface was brown he gnawed it off, and put the rest down to brown again, and so ate a series of laminæ instead of a steak; that it would be cooked to the center if he let it alone was a fact this gentleman had never discovered; probably had never had the patience to discover.

George, finding the shark's flesh detestable, declined it, and watched the other. Presently he vented his reflections. "Well you are a cool one! half an hour ago I didn't expect to see you eating him--quite the contrary." Jacky grinned good-humoredly in reply.

When George returned to the farmer, the latter, who had begun to fear the loss of a customer, came at once to terms with him. The next day he started for home with three hundred sheep. Jacky announced that he should accompany him, and help him a good deal. George's consent was not given, simply because it was not asked. However, having saved the man's life, he was not sorry to see a little more of him.

It is usual in works of this kind to give minute descriptions of people's dress. I fear I have often violated this rule. However I will not in this case.

Jacky's dress consisted of, in front, a sort of purse made of rat-skin; behind, a bran new tomahawk and two spears.

George fancied this costume might be improved upon; he therefore bought from the farmer a second-hand coat and trousers and his new friend donned them with grinning satisfaction. The farmer's wife pitied George living by himself out there, and she gave him several little luxuries; a bacon-ham, some tea, and some orange-marmalade, and a little lump-sugar and some potatoes.

He gave the potatoes to Jacky to carry. They weighed but a few pounds. George himself carried about a quarter of a hundredweight. For all that the potatoes worried Jacky more than George's burden him. At last he loitered behind so long that George sat down and lighted his pipe. Presently up comes Niger with the sleeves of his coat hanging on each side of his neck and the potatoes in them. My lord had taken his tomahawk and chopped off the sleeves at the arm-pit; then he had sewed up their bottoms and made bags of them, uniting them at the other end by a string which rested on the back of his neck like a milkmaid's balance. Being asked what he had done with the rest of the coat, he told George he had thrown it away because it was a good deal hot.

"But it won't be hot at night, and then you will wish you hadn't been such a fool," said George, irate.

No, he couldn't make Jacky see this; being hot at the time Jacky could not feel the cold to come. Jacky became a hanger-on of George, and if he did little he cost little; and if a beast strayed he was invaluable, he could follow the creature for miles by a chain of physical evidence no single link of which a civilized man would have seen.

A quantity of rain having fallen and filled all the pools, George thought he would close with an offer that had been made him and swap one hundred and fifty sheep for cows and bullocks. He mentioned this intention to McLaughlan one Sunday evening. McLaughlan warmly approved his intention. George then went on to name the customer who was disposed to make the exchange in question. At this the worthy McLaughlan showed some little uneasiness and told George he might do better than deal with that person.

George said he should be glad to do better, but did not see how.

"Humph!" said McLaughlan, and fidgeted.

McLaughlan then invited George to a glass of grog, and while they were sipping he gave an order to his man.

McLaughlan inquired when the proposed negotiation was likely to take place. "To-morrow morning," said George. "He asked me to go over about it this afternoon, but I remembered the lesson you gave me about making bargains on this day, and I said 'To-morrow, farmer.'"

"Y're a guid lad," said the Scot demurely; "y're just as decent a body as ever I forgathered wi'--and I'm thinking it's a sin to let ye gang twa miles for mairchandeeze whan ye can hae it a hantle cheaper at your ain door."

"Can I? I don't know what you mean."

"Ye dinna ken what I mean? Maybe no."

Mr. McLaughlan fell into thought a while, and the grog being finished he proposed a stroll. He took George out into the yard, and there the first thing they saw was a score and a half of bullocks that had just been driven into a circle and were maintained there by two men and two dogs.

George's eye brightened at the sight and his host watched it. "Aweel," said he, "has Tamson a bonnier lot than yon to gie ye?"

"I don't know," said George dryly. "I have not seen his."

"But I hae--and he hasna a lot to even wi' them."

"I shall know to-morrow," said George. But he eyed McLaughlan's cattle with an expression there was no mistaking.

"Aweel," said the worthy Scot, "ye're a neebor and a decent lad ye are, sae I'll just speer ye ane question. Noo, mon," continued he in a most mellifluous tone and pausing at every word, "gien it were Monday--as it is the Sabba day--hoo mony sheep wud ye gie for yon bonnie beasties?"

George, finding his friend in this mind, pretended to hang back and to consider himself bound to treat with Thomson first. The result of all which was that McLaughlan came over to him at daybreak and George made a very profitable exchange with him.

At the end of six months more George found himself twice as rich in substance as at first starting; but instead of one hundred pounds cash he had but eighty. Still if sold up he would have fetched five hundred pounds. But more than a year was gone since he began on his own account. "Well," said George, "I must be patient and still keep doubling on, and if I do as well next year as last I shall be worth eight hundred pounds."

A month's dry hot weather came and George had arduous work to take water to his bullocks and to drive them in from long distances to his homestead, where, by digging enormous tanks, he had secured a constant supply. No man ever worked for a master as this rustic Hercules worked for Susan Merton. Prudent George sold twenty bullocks and cows to the first bidder. "I can buy again at a better time," argued he.

He had now one hundred and twenty-five pounds in hand. The drought continued and he wished he had sold more.

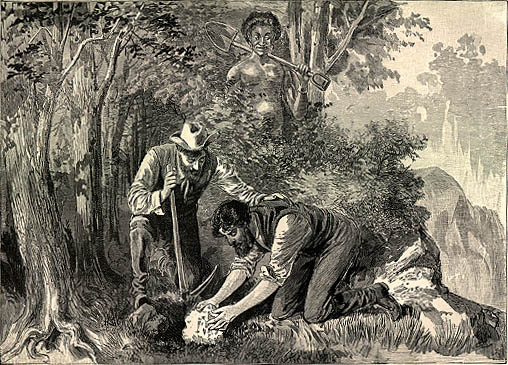

One morning Abner came hastily in and told him that nearly all the beasts and cows were missing. George flung himself on his horse and galloped to the end of his run. No signs of them--returning disconsolate he took Jacky on his crupper and went over the ground with him. Jacky's eyes were playing and sparkling all the time in search of signs. Nothing clear was discovered. Then at Jacky's request they rode off George's feeding-ground altogether and made for a little wood about two miles distant. "Suppose you stop here, I go in the bush," said Jacky.

George sat down and waited. In about two hours Jacky came back. "I've found 'em," said Jacky coolly.

George rose in great excitement and followed Jacky through the stiff bush, often scratching his hands and face. At last Jacky stopped and pointed to the ground, "There!"

"There? ye foolish creature," cried George; "that's ashes where somebody has lighted a fire; that and a bone or two is all I see."

"Beef bone," replied Jacky coolly. George started with horror. "Black fellow burn beef here and eat him. Black fellow a great thief. Black fellow take all your beef. Now we catch black fellow and shoot him suppose he not tell us where the other beef gone."

"But how am I to catch him? How am I even to find him?"

"You wait till the sun so; then black fellow burn more beef. Then I see the smoke; then I catch him. You go fetch the make-thunder with two mouths. When he see him that make him honest a good deal."

Off galloped George and returned with his double-barreled gun in about an hour and a half. He found Jacky where he had left him at the foot of a gumtree tall and smooth as an admiral's main-mast.

Jacky, who was coiled up in happy repose like a dog in warm weather, rose and with a slight yawn said, "Now I go up and look."

He made two sharp cuts on the tree with his tomahawk, and putting his great toe in the nick, rose on it, made another nick higher up, and holding the smooth stem put his other great toe in it, and so on till in an incredibly short time he had reached the top and left a staircase of his own making behind him. He had hardly reached the top when he slid down to the bottom again and announced that he had discovered what they were in search of.

George haltered the pony to the tree and followed Jacky, who struck farther into the wood. After a most disagreeable scramble at the other side of the wood Jacky stopped and put his finger to his lips. They both went cautiously out of the wood, and mounting a bank that lay under its shelter they came plump upon a little party of blacks, four male and three female. The women were seated round a fire burning beef and gnawing the outside laminæ, then putting it down to the fire again. The men, who always serve themselves first, were lying gorged--but at sight of George and Jacky they were on their feet in a moment and their spears poised in their hands.

Jacky walked down the bank and poured a volley of abuse into them. Between two of his native sentences he uttered a quiet aside to George, "Suppose black fellow lift spear you shoot him dead," and then abused them like pickpockets again and pointed to the make-thunder with two mouths in George's hand.

After a severe cackle on both sides the voices began to calm down like water going off the boil, and presently soft low gutturals passed in pleasant modulation. Then the eldest male savage made a courteous signal to Jacky that he should sit down and gnaw. Jacky on this administered three kicks among the gins and sent them flying, then down he sat and had a gnaw at their beef--George's beef, I mean. The rage of hunger appeased, he rose, and with the male savages took the open country. On the way he let George know that these black fellows were of his tribe, that they had driven off the cattle and that he had insisted on restitution--which was about to be made; and sure enough, before they had gone a mile they saw some beasts grazing in a narrow valley. George gave a shout of joy, but counting them he found fifteen short. When Jacky inquired after the others the blacks shrugged their shoulders. They knew nothing more than this, that wanting a dinner they had driven off forty bullocks; but finding they could only eat one that day they had killed one and left the others, of whom some were in the place they had left them; the rest were somewhere, they didn't know where--far less care. They had dined, that was enough for them.

When this characteristic answer reached George he clinched his teeth and for a moment felt an impulse to make a little thunder on their slippery black carcasses, but he groaned instead and said, "They were never taught any better."

Then Jacky and he set to work to drive the cattle together. With infinite difficulty they got them all home by about eleven o'clock at night. The next day up with the sun to find the rest. Two o'clock--and only one had they fallen in with, and the sun broiled so that lazy Jacky gave in and crept in under the beast for shade, and George was fain to sit on his shady side with moody brow and sorrowful heart.

Presently Jacky got up. "I find one," said he.

"Where? where?" cried George, looking all round. Jacky pointed to a rising ground at least six miles off.

George groaned, "Are you making a fool of me? I can see nothing but a barren hill with a few great bushes here and there. You are never taking those bushes for beasts?"

Jacky smiled with utter scorn. "White fellow stupid fellow; he see nothing."

"Well and what does black fellow see?" snapped George.

"Black fellow see a crow coming from the sun, and when he came over there he turned and went down and not get up again a good while. Then black fellow say, 'I tink.' Presently come flying one more crow from that other side where the sun is not. Black fellow watch him, and when he come over there he turn round and go down, too, and not get up a good while. Then black fellow say, 'I know.'"

"Oh, come along!" cried George.

They hurried on; but when they came to the rising ground and bushes Jacky put his finger to his lips. "Suppose we catch the black fellows that have got wings; you make thunder for them?"

He read the answer in George's eye. Then he took George round the back of the hill and they mounted the crest from the reverse side. They came over it and there at their very feet lay one of George's best bullocks, with tongue protruded, breathing his last gasp. A crow of the country was perched on his ribs, digging his thick beak into a hole he had made in his ribs, and another was picking out one of his eyes. The birds rose heavily, clogged and swelling with gore. George's eyes flashed, his gun went up to his shoulder, and Jacky saw the brown barrel rise slowly for a moment as it followed the nearest bird wobbling off with broad back invitingly displayed to the marksman. Bang! the whole charge shivered the ill-omened glutton, who instantly dropped riddled with shot like a sieve, while a cloud of dusky feathers rose from him into the air. The other, hearing the earthly thunder and Jacky's exulting whoop, gave a sudden whirl with his long wing and shot up into the air at an angle and made off with great velocity; but the second barrel followed him as he turned and followed him as he flew down the wind. Bang! out flew two handfuls of dusky feathers, and glutton No. 2 died in the air, and its carcass and expanded wings went whirling like a sheet of paper and fell on the top of a bush at the foot of the hill.

All this delighted the devil-may-care Jacky, but it may be supposed it was small consolation to George. He went up to the poor beast, who died even as he looked down on him.

"Drought, Jacky! drought!" said he--"it is Moses, the best of the herd. Oh, Moses, why couldn't you stay beside me? I'm sure I never let you want for water, and never would--you left me to find worse friends!" and so the poor simple fellow moaned over the unfortunate creature, and gently reproached him for his want of confidence in him that it was pitiful. Then suddenly turning on Jacky he said gravely, "Moses won't be the only one, I doubt."

The words were hardly out of his mouth before a loud moo proclaimed the vicinity of cattle. They ran toward the sound, and in a rocky hollow they found nine bullocks; and alas! at some little distance another lay dead. Those that were alive were panting with lolling tongues in the broiling sun. How to save them; how to get them home a distance of eight miles. "Oh! for a drop of water." The poor fools had strayed into the most arid region for miles round.

Instinct makes blunders as well as reason.--Bestiale est errare.

"We must drive them from this, Jacky, though half of them die by the way."

The languid brutes made no active resistance. Being goaded and beaten they got on their legs and moved feebly away.

Three miles the men drove them, and then one who had been already staggering more than the rest gave in and lay down, and no power could get him up again. Jacky advised to leave him. George made a few steps onward with the other cattle, but then he stopped and came back to the sufferer and sat down beside him disconsolate.

"I can't bear to desert a poor dumb creature. He can't speak, Jacky, but look at his poor frightened eye; it seems to say have you got the heart to go on and leave me to die for the want of a drop of water. Oh! Jacky, you that is so clever in reading the signs of Nature, have pity on the poor thing and do pray try and find us a drop of water. I'd run five miles and fetch it in my hat if you would but find it. Do help us, Jacky." And the white man looked helplessly up to the black savage, who had learned to read the small type of Nature's book and he had not.

Jacky hung his head. "White fellow's eyes always shut; black fellow's always open. We pass here before and Jacky look for water--look for everything. No water here. But," said he languidly, "Jacky will go up high tree and look a good deal." Selecting the highest tree near he chopped a staircase and went up it almost as quickly as a bricklayer mounts a ladder with a hod. At the top he crossed his thighs over the stem, and there he sat full half an hour; his glittering eye reading the confused page, and his subtle mind picking out the minutest syllables of meaning. Several times he shook his head. At last all of a sudden he gave a little start, and then a chuckle, and the next moment he was on the ground.

"What is it?"

"Black fellow stupid fellow--look too far off," and be laughed again for all the world like a jackdaw.

"What is it?"

"A little water; not much."

"Where is it? Where is it? Why don't you tell me where it is?"

"Come," was the answer.

Not forty yards from where they stood Jacky stopped and thrusting his hand into a tuft of long grass pulled out a short blue flower with a very thick stem. "Saw him spark from the top of the tree," said Jacky with a grin. "This fellow stand with him head in the air but him foot in the water. Suppose no water he die a good deal quick." Then taking George's hand he made him press the grass hard, and George felt moisture ooze through the herb.

"Yes, my hand is wet, but, Jacky, this drop won't save a beast's life without it is a frog's."

Jacky smiled and rose. "Where that wet came from more stay behind."

He pointed to other patches of grass close by, and following them showed George that they got larger and larger in a certain direction. At last he came to a hidden nook, where was a great patch of grass quite a different color, green as an emerald. "Water," cried Jacky, "a good deal of water." He took a jump and came down flat on his back on the grass, and sure enough, though not a drop of surface water was visible, the cool liquid squirted up in a shower round Jacky.

Nature is extremely fond of producing the same things in very different sizes. Here was a miniature copy of those large Australian lakes which show nothing to the eye but rank grass. You ride upon them a little way, merely wetting your horse's feet, but after a while the sponge gets fuller and fuller, and the grass shows symptoms of giving way, and letting you down to "bottomless perdition."

They squeezed out of this grass sponge a calabash full of water, and George ran with it to the panting beast. Oh! how he sucked it up, and his wild eye calmed, and the liquid life ran through all his frame!

It was hardly in his stomach before he got up of his own accord, and gave a most sonorous moo, intended no doubt to express the sentiment of "never say die."

George drove them all to the grassy sponge, and kept them there till sunset. He was three hours squeezing out water and giving it them before they were satisfied. Then in the cool of the evening he drove them safe home.

The next day one more of his strayed cattle found his way home. The rest he never saw again. This was his first dead loss of any importance; unfortunately, it was not the last.

The brutes were demoralized by their excursion, and being active as deer they would jump over anything and stray.

Sometimes the vagrant was recovered--often he was found dead; and sometimes he went twenty miles and mingled with the huge herds of some Croesus, and was absorbed like a drop of water and lost to George Fielding. This was a bitter blow. This was not the way to make the thousand pounds.

"Better sell them all to the first comer, and then I shall see the end of my loss. I am not one of your lucky ones. I must not venture."

A settler passed George's way driving a large herd of sheep and ten cows. George gave him a dinner and looked over his stock. "You have but few beasts for so many sheep," said he.

The other assented.

"I could part with a few of mine to you if you were so minded."

The other said he should be very glad, but he had no money to spare. Would George take sheep in exchange?

"Well," drawled George, "I would rather it had been cash, but such as you and I must not make the road hard to one another. Sheep I'll take, but full value."

The other was delighted, and nearly all George's bullocks became his for one hundred and fifty sheep.

George was proud of his bargain, and said, "That is a good thing for you and me, Susan, please God."

Now the next morning Abner came in and said to George, "I don't like some of your new lot--the last that are marked with a red V."

"Why, what is wrong about them?"

"Come and see."

He found more than one of the new sheep rubbing themselves angrily against the pen, and sometimes among one another.

"Oh dear!" said George, "I have prayed against this on my knees every night of my life, and it is come upon me at last. Sharpen your knife, Abner."

"What! must they all--"

"All the new lot. Call Jacky, he will help you; he likes to see blood. I can't abide it. One hundred and fifty sheep; eighteen-pennorth of wool, and eighteen-pennorth of fat when we fling 'em into the pot--that is all that is left to me of yesterday's deal."

Jacky was called.

"Now, Jacky," said George, "these sheep have got the scab of the country; if they get to my flock and taint it I am a beggar from that moment. These sheep are sure to die, so Abner and you are to kill them. He will show you how. I can't look on and see their blood and my means spilled like water. Susan, this is a black day for us!"

He went away and sat down upon a stone a good way off, and turned his back upon his house and his little homestead. This was not the way to make the thousand pounds.

The next day the dead sheep were skinned and their bodies chopped up and flung into the copper. The grease was skimmed as it rose, and set aside, and when cool was put into rough barrels with some salt and kept up until such time as a merchant should pass that way and buy it.

"Well!" said George, with a sigh, "I know my loss. But if the red scab had got into the large herd, there would have been no end to the mischief."

Soon after this a small feeder at some distance offered to change with McLaughlan. That worthy liked his own ground best, but willing to do his friend George a good turn he turned the man over to him. George examined the new place, found that it was smaller but richer and better watered, and very wisely closed with the proposal.

When he told Jacky that worthy's eyes sparkled.

"Black fellow likes another place. Not every day the same."

And in fact he let out that if this change had not occurred his intention had been to go a-hunting for a month or two, so weary had he become of always the same place.

The new ground was excellent, and George's hopes, lately clouded, brightened again. He set to work and made huge tanks to catch the next rain, and as heretofore did the work of two.

It was a sad thing to have to write to Susan and tell her that after twenty months' hard work he was just where he had been at first starting. One day, as George was eating his homely dinner on his knee by the side of his principal flock, he suddenly heard a tremendous scrimmage mixed with loud, abusive epithets from Abner. He started up, and there was Carlo pitching into a sheep who was trying to jam herself into the crowd to escape him. Up runs one of the sheep-dogs growling, but instead of seizing Carlo, as George thought he would, what does he do but fall upon another sheep, and spite of all their evasions the two dogs drove the two sheep out of the flock and sent them pelting down the hill. In one moment George was alongside Abner.

"Abner," said he, "how came you to let strange sheep in among mine?"

"Never saw them till the dog pinned them."

"You never saw them," said George reproachfully. "No, nor your dog either till my Carlo opened your eyes. A pretty thing for a shepherd and his dog to be taught by a pointer. Well," said George, "you had eyes enough to see whose sheep they were. Tell me that, if you please?"

Abner looked down.

"Why, Abner?"

"I'd as lieve bite off my tongue as tell you."

George looked uneasy and his face fell.

"A 'V.' Don't ye take on," said Abner. "They couldn't have been ten minutes among ours, and there were but two. And don't you blow me up, for such a thing might happen to the carefulest shepherd that ever was."

"I won't blow ye up, Will Abner," said George. "It is my luck not yours that has done this. It was always so. From a game of cricket upward I never had my neighbor's luck. If the flock are not tainted I'll give you five pounds, and my purse is not so deep as some. If they are, take your knife and drive it into my heart. I'll forgive you that as I do this. Carlo! let me look at you. See here, he is all over some stinking ointment. It is off those sheep. I knew it. 'Twasn't likely a pointer dog would be down on strange sheep like a shepherd's dog by the sight. 'Twas this stuff offended him. Heaven's will be done."

"Let us hope the best, and not meet trouble half way."

"Yes" said George feebly. "Let us hope the best."

"Don't I hear that Thompson has an ointment that cures the red scab?"

"So they say."

George whistled to his pony. The pony came to him. George did not treat him as we are apt to treat a horse--like a riding machine. He used to speak to him and caress him when he fed him and when he made his bed, and the horse followed him about like a dog.

In half an hour's sharp riding they were at Thompson's, an invaluable man that sold and bought animals, doctored animals, and kept a huge boiler in which bullocks were reduced to a few pounds of grease in a very few hours.

"You have an ointment that is good for the scab, sir?"

"That I have, farmer. Sold some to a neighbor of yours day before yesterday."

"Who was that?"

"A newcomer. Vesey is his name."

George groaned. "How do you use it, if you please?"

"Shear 'em close, rub the ointment well in, wash 'em every two days, and rub in again."

"Give me a stone of it."

"A stone of my ointment! Well! you are the wisest man I have come across this year or two. You shall have it, sir."

George rode home with his purchase.

Abner turned up his nose at it, and was inclined to laugh at George's fears. But George said to himself, "I have Susan to think of as well as myself. Besides," said he a little bitterly, "I haven't a grain of luck. If I am to do any good I must be twice as prudent and thrice as industrious as my neighbors or I shall fall behind them. Now, Abner, we'll shear them close."

"Shear them! Why it is not two months since they were all sheared."

"And then we will rub a little of this ointment into them."

"What! before we see any sign of the scab among them? I wouldn't do that if they were mine."

"No more would I if they were yours," replied George almost fiercely. "But they are not yours, Will Abner. They are unlucky George's."

During the next three days four hundred sheep were clipped and anointed. Jacky helped clip, but he would not wear gloves, and George would not let him handle the ointment without them, suspecting mercury.

At last George yielded to Abner's remonstrances, and left off shearing and anointing.

Abner altered his opinion when one day he found a sheep rubbing like mad against a tree, and before noon half a dozen at the same game. Those two wretched sheep had tainted the flock.

Abner hung his head when he came to George with this ill-omened news. He expected a storm of reproaches. But George was too deeply distressed for any petulances of anger. "It is my fault," said he, "I was the master, and I let my servant direct me. My own heart told me what to do, yet I must listen to a fool and a hireling that cared not for the sheep. How should he? they weren't his, they were mine to lose and mine to save. I had my choice, I took it, I lost them. Call Jacky and let's to work and save here and there one, if so be God shall be kinder to them than I have been."

From that hour there was but little rest morning, noon or night. It was nothing but an endless routine of anointing and washing, washing and anointing sheep. To the credit of Mr. Thompson it must be told that of the four hundred who had been taken in time no single sheep died; but of the others a good many. There are incompetent shepherds as well as incompetent statesmen and doctors, though not so many. Abner was one of these. An acute Australian shepherd would have seen the more subtle signs of this terrible disease a day or two before the patient sheep began to rub themselves with fury against the trees and against each other; but Abner did not; and George did not profess to have a minute knowledge of the animal, or why pay a shepherd? When this Herculean labor and battle had gone on for about a week, Abner came to George, and with a hang-dog look begged him to look out for another shepherd.

"Why, Will! surely you won't think to leave me in this strait? Why three of us are hardly able for the work, and how can I make head against this plague with only the poor sav--with only Jacky, that is first-rate at light work till he gets to find it dull--but can't lift a sheep and fling her into the water, as the like of us can?"

"Well, ye see," said Abner, doggedly, "I have got the offer of a place with Mr. Meredith, and he won't wait for me more than a week."

"He is a rich man, Will, and I am a poor one," said George in a faint, expostulating tone. Abner said nothing, but his face showed he had already considered this fact from his own point of view.

"He could spare you better than I can; but you are right to leave a falling house that you have helped to pull down."

"I don't want to go all in a moment. I can stay a week till you get another."

"A week! how can I get a shepherd in this wilderness at a week's notice? You talk like a fool."

"Well, I can't stay any longer. You know there is no agreement at all between us, but I'll stay a week to oblige you."

"You'll oblige me, will you?" said George, with a burst of indignation; "then oblige me by packing up your traps and taking your ugly face out of my sight before dinner-time this day. Stay, my man, here are your wages up to twelve o'clock to-day, take 'em and out of my sight, you dirty rascal. Let me meet misfortune with none but friends by my side. Away with you, or I shall forget myself and dirty my hands with your mean carcass."

The hireling slunk off, and as he slunk George stormed and thundered after him, "And wherever you may go, may sorrow and sickness--no!"

George turned to Jacky, who sat coolly by, his eyes sparkling at the prospect of a row. "Jacky!" said he, and then he seemed to choke, and could not say another word.

"Suppose I get the make-thunder, then you shoot him."

"Shoot him! what for?"

"Too much bungality,* shoot him dead. He let the sheep come that have my two fingers so on their backs;" here Jacky made a V with his middle and forefinger, "so he kill the other sheep--yet still you not shoot him--that so stupid I call."

* Stupidity.

"Oh Jacky, hush! don't you know me better than to think I would kill a man for killing my sheep. Oh fie! oh fie! No, Jacky, Heaven forbid I should do the man any harm; but when I think of what he has brought on my head, and then to skulk and leave me in my sore strait and trouble, me that never gave him ill language as most masters would; and then, Jacky, do you remember when he was sick how kind you and I were to him--and now to leave us. There, I must go into the house, and you come and call me out when that man is off the premises--not before."

At twelve o'clock selfish Abner started to walk thirty miles to Mr. Meredith's. Smarting under the sense of his contemptibleness and of the injury he was doing his kind, poor master, he shook his fist at the house and told Jacky he hoped the scab would rot the flock, and that done fall upon the bipeds, on his own black hide in particular. Jacky only answered with his eye. When the man was gone he called George.

George's anger had soon died. Jacky found him reading a little book in search of comfort, and when they were out in the air Jacky saw that his eyes were rather red.

"Why you cry?" said Jacky. "I very angry because you cry."

"It is very foolish of me," said George, apologetically, "but three is a small company, and we in such trouble; I thought I had made a friend of him. Often I saw he was not worth his wages, but out of pity I wouldn't part with him when I could better have spared him than he me, and now--there--no more about it. Work is best for a sore heart, and mine is sore and heavy, too, this day."

Jacky put his finger to his head, and looked wise. "First you listen me--this one time I speak a good many words. Dat stupid fellow know nothing, and so because you not shoot him a good way* behind--you very stupid. One," counted Jacky, touching his thumb, "he know nothing with these (pointing to his eyes). Jacky know possum,** Jacky know kangaroo, know turkey, know snake, know a good many, some with legs like dis (four fingers), some with legs like dis (two flngers)--dat stupid fellow know nothing but sheep, and not know sheep, let him die too much. Know nothing with 'um eyes. One more (touching his forefinger). Know nothing with dis (touching his tongue). Jacky speak him good words, he speak Jacky bad words. Dat so stupid--he know nothing with dis.

* Long ago.

** Opossum.

"One more. You do him good things--he do you bad things; he know nothing with these (indicating his arms and legs as the seat of moral action), so den because you not shoot him long ago now you cry; den because you cry Jacky angry. Yes, Jacky very good. Jacky a little good before he live with you. Since den very good--but when dat fellow know nothing, and now you cry at the bottom* part Jacky a little angry, and Jacky go hunting a little not much direckly."

*At last.

With these words the savage caught up his tomahawk and two spears, and was going across country without another word, but George cried out in dismay, "Oh, stop a moment! What! to-day, Jacky? Jacky, Jacky, now don't ye go to-day. I know it is very dull for the likes of you, and you will soon leave me, but don't ye go to-day; don't set me against flesh and blood altogether."

"I come back when the sun there," pointing to the east, "but must hunt a little, not much. Jacky uncomfortable," continued he, jumping at a word which from its size he thought must be of weight in any argument, "a good deal uncomfortable suppose I not hunt a little dis day."

"I say no more, I have no right--goodby, take my hand, I shall never see you any more.

"I shall come back when the sun there."

"Ah! well I daresay you think you will. Good-by, Jacky; don't you stay to please me."

Jacky glided away across country. He looked back once and saw George watching him. George was sitting sorrowful upon a stone, and as this last bit of humanity fell away from him and melted away in the distance his heart died within him. "He thinks he will come back to me, but when he gets in the open and finds the track of animals to hunt he will follow them wherever they go, and his poor shallow head won't remember this place nor me; I shall never see poor Jacky any more!"

The black continued his course for about four miles until a deep hollow hid him from George. Arrived here he instantly took a line nearly opposite to his first, and when he had gone about three miles on this tack he began to examine the ground attentively and to run about like a hound. After near half an hour of this he fell upon some tracks and followed them at an easy trot across the country for miles and miles, his eye keenly bent upon the ground.

OUR story has to follow a little way an infinitesimal personage.

Abner, the ungratefulish one, with a bundle tied up in a handkerchief, strode stoutly away toward Mr. Meredith's grazing ground. "I am well out of that place," was his reflection. As he had been only once over the ground before, he did not venture to relax his pace lest night should overtake him in a strange part. He stepped out so well that just before the sun set he reached the head of a broad valley that was all Meredith's. About three miles off glittered a white mansion set in a sea of pasture, studded with cattle instead of sails. "Ay! ay!" thought the ungratefulish one, no fear of the scab breaking up this master--"I'm all right now." As he chuckled over his prospects a dusky figure stole noiselessly from a little thicket--an arm was raised behind him--crosssh! a hard weapon came down on his skull, and he lay on his face with the blood trickling from his mouth and ears.

HE who a few months ago was so lighthearted and bright with hope now rose at daybreak for a work of Herculean toil as usual, but no longer with the spirit that makes labor light. The same strength, the same dogged perseverance were there, but the sense of lost money, lost time, and invincible ill-luck oppressed him; then, too, he was alone--everything had deserted him but misfortune.

"I have left my Susan and I have lost her--left the only friend I had or ever shall have in this hard world." This was his constant thought, as doggedly but hopelessly he struggled against the pestilence. Single-handed and leaden-hearted he had to catch a sheep, to fling her down, to hold her down, to rub the ointment into her, and to catch another that had been rubbed yesterday and take her to the pool and fling her in and keep her in till every part of her skin was soaked.

Four hours of this drudgery had George gone through single-handed and leaden-hearted, when as he knelt over a kicking, struggling sheep, he became conscious of something gliding between him and the sun; he looked up and there was Jacky grinning.

George uttered an exclamation: "What, come back! Well, now that is very good of you I call. How do you do?" and he gave him a great shake of the hand.

"Jacky very well, Jacky not at all uncomfortable after him hunt a little."

"Then I am very glad you have had a day's sport, leastways a night's, I call it, since it has made you comfortable, Jacky."

"Oh! yes, very comfortable now," and his white teeth and bright eye proclaimed the relief and satisfaction his little trip had afforded his nature.

"There, Jacky, if the ointment is worth the trouble it gives me rubbing of it in, that sheep won't ever catch the scab, I do think. Well, Jacky, seems to me I ought to ask your pardon--I did you wrong. I never expected you would leave the kangaroos and opossums for me once you were off. But I suppose fact is you haven't quite forgotten Twofold Bay."

"Two fool bay!" inquired Jacky, puzzled.

"Where I first fell in with you. You made one in a hunt that day, only instead of hunting you was hunted and pretty close, too, and if I hadn't been a good cricketer and learned to fling true-- Why, I do declare I think he has forgotten the whole thing, shark and all!"

At the word shark a gleam of intelligence came to the black's eye; it was succeeded by a look of wonder. "Shark come to eat me--you throw stone--so we eat him. I see him now a little--a very little--dat a long way off--a very long way off. Jacky can hardly see him when he try a good deal. White fellow see a long way off behind him back--dat is very curious."

George colored. "You are right, lad--it was a long while ago, and I am vexed for mentioning it. Well, any way you are come back and you are welcome. Now you shall do a little of the light work, but I'll do all the heavy work because I'm used to it;" and indeed poor George did work and slave like Hercules; forty times that day he carried a full-sized sheep in his hands a distance of twenty yards and flung her into the water and splashed in and rubbed her back in the water.

The fourth day after Jacky's return George asked him to go all over the ground and tell him how many sheep he saw give signs of the fatal disorder.

About four o'clock in the afternoon Jacky returned driving before him with his spear a single sheep. The agility of both the biped and quadruped were droll; the latter every now and then making a rapid bolt to get back to the pasture and Jacky bounding like a buck and pricking her with a spear.

For the first time he found George doing nothing. "Dis one scratch um back--only dis one."

"Then we have driven out the murrain and the rest will live. A hard fight! Jacky, a hard fight! but we have won it at last. We will rub this one well; help me put her down, for my head aches."

After rubbing her a little George said, "Jacky, I wish you would do it for me, for my head do ache so I can't abide to hold it down and work, too."

After dinner they sat and looked at the sheep feeding. "No more dis," said Jacky gayly, imitating a sheep rubbing against a tree.

"No! I have won the day; but I haven't won it cheap. Jacky, that fellow, Abner, was a bad man--an ungrateful man."

These words George spoke with a very singular tone of gravity.

"Never you mind you about him."

"No! I must try to forgive him; we are all great sinners; is it cold to-day?"

"No! it is a good deal hot

"I thought it must, for the wind is in a kindly quarter. Well, Jacky, I am as cool as ice."

"Dat very curious."

"And my head do ache so I can hardly bear myself."

"You ill a little--soon be well."

"I doubt I shall be worse before I am better."

"Never you mind you. I go and bring something I know. We make it hot with water, den you drink it; and after dat you a good deal better."

"Do, Jacky. I won't take doctor's stuff; it is dug out of the ground and never was intended for man's inside. But you get me something that grows in sight and I'll take that; and don't be long, Jacky--for I am not well."

Jacky returned toward evening with a bundle of simples. He found George shivering over a fire. He got the pot and began to prepare an infusion. "Now you soon better," said he.

"I hope so, Jacky," said George very gravely, "thank you, all the same. Jacky, I haven't been not to say dry for the last ten days with me washing the sheep, and I have caught a terrible chill--a chill like death; and, Jacky, I have tried too much--I have abused my strength. I am a very strong man as men go, and so was my father; but he abused his strength--and he was took just as I am took now, and in a week he was dead. I have worked hard ever since I came here, but since Abner left me at the pinch it hasn't been man's work, Jacky; it has been a wrestling-match from dawn to dark. No man could go on so and not break down; but I wanted so to save the poor sheep. Well, the sheep are saved; but--"

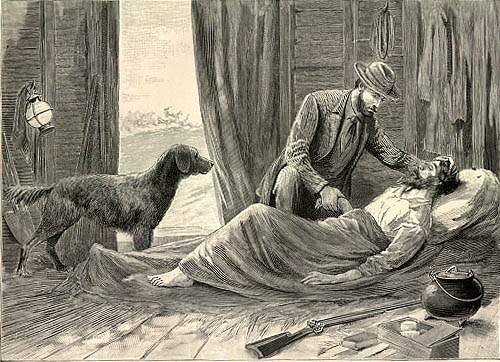

When Jacky's infusion was ready he made George take it and then lie down. Unfortunately the attack was too violent to yield to this simple remedy. Fever was upon George Fielding--fever in his giant shape; not as he creeps over the weak, but as he rushes on the strong. George had never a headache in his life before. Fever found him full of blood and turned it all to fire. He tossed--he raged--and forty-eight hours after his first seizure the strong man lay weak as a child, except during those paroxysms of delirium which robbed him of his reason while they lasted, and of his strength when they retired.

On the fourth day---after a raging paroxysm--he became suddenly calm, and looking up saw Jacky seated at some little distance, his bright eye fixed upon him.

"You better now?" inquired he, with even more than his usual gentleness of tone. "You not talk stupid things any more?"

"What, Jacky, are you watching me?" said the sick man. "Now I call that very kind of you. Jacky, I am not the man I was--we are cut down in a day like the ripe grass. How long is it since I was took ill?"

"One, one, one, and one more day."

"Ay! Ay! My father lasted till the fifth day, and then--Jacky!"

"Here Jacky! what you want?"

"Go out on the hill and see whether any of the sheep are rubbing themselves."

Jacky went out and soon returned.

"Not see one rub himself."

A faint gleam lighted George's sunken eye. "That is a comfort. I hope I shall be accepted not to have been a bad shepherd, for I may say 'I have given my life for my sheep.' Poor things."

George dozed. Toward evening he awoke, and there was Jacky just where he had seen him last. "I didn't think you had cared so much for me, Jacky, my boy."

"Yes, care very much for you. See, um make beef-water for you a good deal."

And sure enough he had boiled down about forty pounds of beef and filled a huge calabash with the extract, which he set by George's side.

"And why are you so fond of me, Jacky? It isn't on account of my saving your life, for you had forgotten that. What makes you such a friend to me?"

"I tell you. Often I go to tell you before, but many words dat a good deal trouble. One--when you make thunder the bird always die. One--you take a sheep so and hold him up high. Um never see one more white fellow able do dat. One--you make a stone go and hit thing; other white fellow never hit. One--little horse come to you; other white fellow go to horse--horse run away. Little horse run to you, dat because you so good. One--Carlo fond of you. All day now he come in and go out, and say so (imitating a dog's whimper). He so uncomfortable because you lie down so. One--when you speak to Jacky you not speak big like white fellow, you speak small and like a fiddle--dat please Jacky's ear.

"One--when you look at Jacky always your face make like a hot day when dere no rain--dat please Jacky's eye; and so when Jacky see you stand up one day a good deal high and now lie down--dat makes him uncomfortable; and when he see you red one day and white dis day--dat make him uncomfortable a good deal; and when he see you so beautiful one day and dis day so ugly--dat make him so uncomfortable, he afraid you go away and speak no more good words to Jacky--and dat make Jacky feel a thing inside here (touching his breast), no more can breathe--and want to do like the gin, but don't know how. Oh, dear! don't know how!"

"Poor Jacky! I do wish I had been kinder to you than I have. Oh, I am very short of wind, and my back is very bad!"

"When black fellow bad in um back he always die," said Jacky very gravely.

"Ay," said George quietly. "Jacky, will you do one or two little things for me now?"

"Yes, do um all."

"Give me that little book that I may read it. Thank you. Jacky, this is the book of my religion; and it was given to me by one I love better than all the world. I have disobeyed her--I have thought too little of what is in this book and too much of this world's gain. God forgive me! and I think He will, because it was for Susan's sake I was so greedy of gain."

Jacky looked on awestruck as George read the book of his religion. "Open the door, Jacky."

Jacky opened the door; then coming to George's side, he said with an anxious, inquiring look and trembling voice, "Are you going to leave me, George?"

"Yes, Jacky, my boy," said George, "I doubt I am going to leave you. So now thank you and bless you for all kindness. Put your face close down to mine-there--I don't care for your black skin--He who made mine made yours; and I feel we are brothers, and you have been one to me. Good-by, dear, and don't stay here. You can do nothing more for your poor friend George."

Jacky gave a little moan. "Yes, um can do a little more before he go and hide him face where there are a good deal of trees."

Then Jacky went almost on tiptoe, and fetched another calabash full of water and placed it by George's head. Then he went very softly and fetched the heavy iron which he had seen George use in penning sheep, and laid it by George's side; next he went softly and brought George's gun, and laid it gently by George's side down on the ground.

This done he turned to take his last look of the sick man now feebly dozing, the little book in his drooping hand. But as he gazed nature rushed over the poor savage's heart and took it quite by surprise. Even while bending over his white brother to look his last farewell, with a sudden start he turned his back on him, and sinking on his hams he burst out crying and sobbing with a wild and terrible violence.

FOR near an hour Jacky sat upon the ground, his face averted from his sick friend, and cried; then suddenly he rose, and without looking at him went out at the door, and turning his face toward the great forests that lay forty miles distant eastward, he ran all the night, and long before dawn was hid in the pathless woods.

A white man feels that grief, when not selfish, is honorable, and unconsciously he nurses such grief more or less; but to simple-minded Jacky grief was merely a subtle pain, and to be got rid of as quickly as possible, like any other pain.

He ran to the vast and distant woods, hoping to leave George's death a long way behind him, and so not see what caused his pain so plain as he saw it just now. It is to be observed that he looked upon George as dead. The taking into his hand of the book of his religion, the kind embrace, the request that the door might be opened, doubtless for the disembodied spirit to pass out, all these rites were understood by Jacky to imply that the last scene was at hand. Why witness it? it would make him still more uncomfortable. Therefore he ran, and never once looked back, and plunged into the impenetrable gloom of the eastern forests.

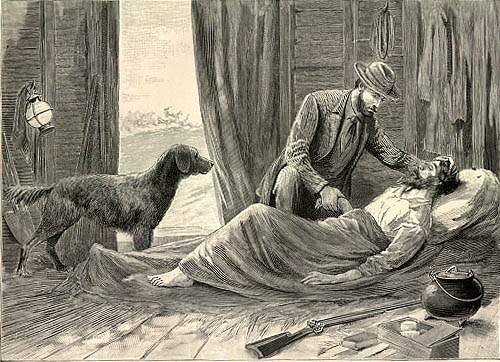

The white man had left Fielding to get a richer master. The half-reasoning savage left him to cure his own grief at losing him. There he lay abandoned in trouble and sickness by all his kind. But one friend never stirred; a single-hearted, single-minded, non-reasoning friend.

Who was this pure-minded friend? A dog.

Carlo loved George. They had lived together, they had sported together, they had slept together side by side on the cold, hard deck of the Phoenix, and often they had kept each other warm, sitting crouched together behind a little bank or a fallen tree, with the wind whistling and the rain shooting by their ears.

When day after day George came not out of the house, Carlo was very uneasy. He used to patter in and out all day, and whimper pitifully, and often he sat in the room where George lay and looked toward him and whined. But now when his master was left quite alone his distress and anxiety redoubled; he never went ten yards away from George. He ran in and out moaning and whining, and at last he sat outside the door and lifted up his voice and howled day and night continually. His meaner instincts lay neglected; he ate nothing; his heart was bigger than his belly; he would not leave his friend even to feed himself. And still day and night without cease his passionate cry went up to heaven.

What passed in that single heart none can tell for certain but his Creator; nor what was uttered in that deplorable cry; love, sorrow, perplexity, dismay--all these perhaps, and something of prayer--for still he lifted his sorrowful face toward heaven as he cried out in sore perplexity, distress, and fear for his poor master--oh! o-o-o-h! o-o-o-o-h! o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-h!

So we must leave awhile poor, honest, unlucky George, sick of a fever, ten miles from the nearest hut.

Leather-heart has gone from him to be a rich man's hireling.

Shallow-heart has fled to the forest, and is hunting kangaroos with all the inches of his soul.

Single-heart sits fasting from all but grief before the door, and utters heartrending, lamentable cries to earth and heaven.

---- JAIL is still a grim and castellated mountain of masonry, but a human heart beats and a human brain throbs inside it now.

Enter without fear of seeing children kill themselves, and bearded men faint like women, or weep like children--horrible sights.

The prisoners no longer crouch and cower past the officers, nor the officers look at them and speak to them as if they were dogs, as they do in most of these places, and used to here.

Open this cell. A woman rises with a smile! why a smile? Because for months an open door has generally let in what is always a great boon to a separate prisoner--a human creature with a civil word. We remember when an open door meant "way for a ruffian and a fool to trample upon the solitary and sorrowful!"

What is this smiling personage doing? as I live she is watchmaking! A woman watchmaking, with neat and taper fingers, and a glass at her eye sometimes, but not always, for in vision as well as in sense of touch and patience nature has been bounteous to her. She is one of four. Eight, besides these four, were tried and found incapable of excellence in this difficult craft. They were put to other things; for permanent failures are not permitted in ---- Jail. The theory is that every home can turn some sort of labor to profit.

Difficulties occur often. Impossibilities will bar the way now and then; but there are so few real impossibilities. When a difficulty arises, the three hundred industrious arts and crafts are freely ransacked for a prisoner; ay!--ransacked as few rich men would be bothered to sift the seven or eight liberal professions in order to fit a beloved son.

Here, as in the world, the average of talent is low. The majority can only learn easy things, and vulgar things, and some can do higher things and a few can do beautiful things, and one or two have developed first-rate gifts and powers.

There are 25 shoemakers (male); 12 tailors, of whom 6 female; 24 weavers, of whom 10 female; 4 watchmakers, all female; 6 printers and composers, 5 female; 4 engrainers of wood, 2 female. (In this art we have the first artist in Britain, our old acquaintance, Thomas Robinson. He has passed all his competitors by a simple process. Beautiful specimens of all the woods have been placed and kept before him, and for a month he has been forced to imitate nature with his eye never off her. His competitors in the world imitate nature from memory, from convention, or from tradition. By such processes truth and beauty are lost at each step down the ladder of routine. Mr. Eden gave clever Tom at first starting the right end of the stick, instead of letting him take the wrong.) Nine joiners and carpenters, 3 female; 3 who color prints downright well, 1 female; 2 painters, 1 female; 3 pupils shorthand writing, 1 female.

[Fancy these attending the Old Bailey and taking it all down solemn as judges.]

Workers in gutta-percha, modelers in clay, washers and getters-up of linen, hoe-makers, spade-makers, rake-makers, woodcarvers, stonecutters, bakers, etc., etc., etc., ad infinitum. Come to the hard-labor yard. Do you see those fifteen stables? there lurk in vain the rusty cranks; condemned first as liars they fell soon after into disrepute as weapons of half-science to degrade minds and bodies. They lurk there grim as the used-up giants in "Pilgrim's Progress," and like them can't catch a soul.

Hark to the music of the shuttle and the useful loom. We weave linen, cotton, woolen, linsey-woolsey, and, not to be behind the rogues outside, cottonsey-woolsey and cottonsey-silksey; damask we weave, and a little silk and poplin, and Mary Baker velvet itself for a treat now and then. We of the loom relieve the county of all expense in keeping us, and enrich a fund for taking care of discharged industrious prisoners until such time as they can soften prejudices and obtain lucrative employment. The old plan was to kick a prisoner out and say:

"There, dog! go without a rap among those who will look on you as a dog and make you starve or steal. We have taught you no labor but crank, and as there are no cranks in the outside world, the world not being such an idiot as we are, you must fill your belly by means of the only other thing you have ever been taught--theft."

Now the officers take leave of a discharged prisoner in English. Farewell; good-by!--a contraction for God be wi' ye--etc. It used to be in French, Sans adieu! au revoir! and the like.

Having passed the merry, useful looms open this cell. A she-thief looks up with an eye six times as mellow as when we were here last. She is busy gilding. See with what an adroit and delicate touch the jade slips the long square knife under the gossamer gold-leaf which she has blown gently out of the book--and turns it over; and now she breathes gently and vertically on the exact center of it, and the fragile yet rebellious leaf that has rolled itself up like a hedgehog is flattened by that human zephyr on the little leathern easel. Now she cuts it in three with vertical blade; now she takes her long flat brush and applies it to her own hair once or twice; strange to say the camel-hair takes from this contact a soupçon of some very slight and delicate animal oil, which enables the brush to take up the gold-leaf, and the artist lays a square of gold in its place on the plaster bull she is gilding. Said bull was cast in the prison by another female prisoner who at this moment is preparing a green artificial meadow for the animal to stand in. These two girls had failed at the watchmaking. They had sight and the fine sensation of touch required, but they lacked the caution, patience and judgment so severe an art demanded; so their talents were directed elsewhere. This one is a first-rate gilder, she mistressed it entirely in three days.

The last thing they did in this way was an elephant. Cost of casting him, reckoning labor and the percentage he ought to pay to the mold, was 1s. 4d. Plaster, chrome, water-size and oil-size, 3d.; goldleaf, 3s.; 1 foot of German velvet, 4d.; thread, needles and wear of tools, 1d.; total, 5s.

Said gold elephant standing on a purple cushion was subjected to a severe test of his value. He was sent to a low auction room in London. There he fell to the trade at 18s. This was a "knock-out" transaction; twelve buyers had agreed not to bid against one another in the auction room, a conspiracy illegal but customary. The same afternoon these twelve held one of their little private unlawful auctions over him; here the bidding was like drops of blood oozing from flints, but at least it was bona-fide, and he rose to 25s. The seven shillings premium was divided among the eleven sharpers. Sharper No. 12 carried him home and sold him the very next day for 37s. to a lady who lived in Belgravia, but shopped in filthy alleys, misled perhaps by the phrase "dirt cheap."

Mr. Eden conceived him, two detected ones made him at a cost of 5s., twelve undetected ones caught him first for 18s., and now he stands in Belgravia, and the fair ejaculate over him, "What a duck!"

The aggregate of labor to make and gild this elephant was not quite one woman's work (12 hours). Taking 18s. as the true value of the work, for in this world the workman has commonly to sell his production under the above disadvantages, forced sale and the conspiracies of the unimprisoned--we have still 13s. for a day's work by a woman.

From the bull greater things are expected. The cast is from the bull of the Vatican, a bull true to Nature, and Nature adorned the very meadows when she produced the bull. What a magnificent animal is a bull! what a dewlap! what a front! what clean pasterns! what fearless eyes! what a deep diapason is his voice! of which beholding this his true and massive effigy in ---- Jail we are reminded. When he stands muscular, majestic, sonorous, gold, in his meadow pied with daisies, it shall not be "sweet" and "love" and "duck"--words of beauty but no earthly signification; it shall be, "There, I forgive Europa."

And need I say there were more aimed at in all this than pecuniary profit. Mr. Eden held that the love of production is the natural specific antidote to the love of stealing. He kindled in his prisoners the love of producing, of what some by an abuse of language call "creating." And the producers rose in the scale of human beings. Their faces showed it--the untamed look melted away--the white of the eye showed less, and the pupil and iris more, and better quality.

Gold-leaf when first laid on adheres in visible squares with uncouth edges, a ragged affair; then the gilder takes a camelhair brush and under its light and rapid touch the work changes as under a diviner's rod, so rapidly and majestically come beauty and finish over it. Perhaps no other art has so delicious a one minute as this is to the gilder. The first work our prisoner gilded she screamed with delight several times at this crisis. She begged to have the work left in her cell one day at least. "It lights up the cell and lights up my heart."

"Of course it does," said Mr. Eden. "Aha! what, there are greater pleasures in the world than sinning, are there?"

"That there are. I never was so pleased in my life. May I have it a few minutes?"

"My child, you shall have it till its place is taken by others like it. Keep it before your eyes, feed on it, and ask yourself which is the best, to work and add something useful or beautiful to the world's material wealth, or to steal; to be a little benefactor to your kind and yourself, or a little vermin preying on the industrious. Which is best?"

"I'll never take while I can make."

This is, of course, but a single specimen out of scores. To follow Mr. Eden from cell to cell, from mind to mind, from sex to sex, would take volumes and volumes. I only profess to reveal fragments of such a man. He never hoped from the mere separate cell the wonders that dreamers hope. It was essential to the reform of prisoners that moral contagion should be checkmated, and the cell was the mode adopted, because it is the laziest, cheapest, selfishest and cruelest way of doing this. That no discretion was allowed him to let the converted or the well-disposed mix and sympathize, and compare notes, and confirm each other in good under a watchful officer's eye; this he thought a frightful blunder of the system.

Generally he held the good effect of separate confinement to be merely negative; he laughed to scorn the chimera that solitude is an active agent, capable of converting a rogue. Shut a rogue from rogues and let honest men in upon him--the honest men get a good chance to convert him, but if they do succeed it was not solitude that converted him but healing contact. The moments that most good comes to him are the moments his solitude is broken.

He used to say solitude will cow a rogue and suspend his overt acts of theft by force, and so make him to a non-reflector seem no longer a thief; but the notion of the cell effecting permanent cures might honestly be worded thus: "I am a lazy self-deceiver, and want to do by machinery and without personal fatigue what St. Paul could only do by working with all his heart, with all his time, with all his wit, with all his soul, with all his strength and with all himself." Or thus: "Confine the leopards in separate cages, Jock; the cages will take their spots out while ye're sleeping."

Generally this was Mr. Eden's theory of the cell--a check to further contamination, but no more. He even saw in the cell much positive ill which he set himself to qualify.

"Separate confinement breeds monstrous egotism," said he, "and egotism hardens the heart. You can't make any man good if you never let him say a kind word or do an unselfish action to a fellow-creature. Man is an acting animal. His real moral character all lies in his actions, and none of it in his dreams or cogitations. Moral stagnation or cessation of all bad acts and of all good acts is a state on the borders of every vice and a million miles from virtue."

His reverence attacked the petrifaction and egotism of the separate cell as far as the shallow system of this prison let him. First, he encouraged prisoners to write their lives for the use of the prison; these were weeded, if necessary (the editor was strong-minded and did not weed out the re-poppies); printed and circulated in the jail. The writer's number was printed at the foot if he pleased, but never his name. Biography begot a world of sympathy in the prison. Second, he talked to one prisoner acquainted with another prisoner's character, talked about No. 80 to No. 60, and would sometimes say: "Now could you give No. 60 any good advice on this point?"

Then if 80's advice was good he would carry it to 60, and 60 would think all the more of it that it came from one of his fellows.

Then in matters of art he would carry the difficulties of a beginner or a bungler to a proficient, and the latter would help the former. The pleasure of being kind on one side, a touch of gratitude on the other, seeds of interest and sympathy in both. Then such as had produced pretty things were encouraged to lend them to other cells to adorn them and stimulate the occupants.

For instance, No. 140, who gilded the bull, was reminded that No. 120, who had cast him, had never had the pleasure of setting him on her table in her gloomy cell and so raising its look from dungeon to workshop. Then No. 140 said, "Poor No. 120! that is not fair; she shall have him half the day or more if you like, sir."

Thus a grain of self-denial, justice and charity was often drawn into the heart of a cell through the very keyhole.

No. 19, Robinson, did many a little friendly office for other figures, received their thanks, and, above all, obliging these figures warmed and softened his own heart.

You might hear such dialogues as this:

No. 24. "And how is poor old No. 50 to-day (Strutt)?"

Mr. Eden. "Much the same."

No. 24. "Do you think you will bring him round, sir?"

Mr. Eden. "I have great hopes; he is much improved since he had the garden and the violin."

No. 24. "Will you give him my compliments, sir? No. 24's compliments and tell him I bid him 'never say die'?"

Mr. Eden. "Well, ----, how are you this morning?"

"I am a little better, sir. This room (the infirmary) is so sweet and airy, and they give me precious nice things to eat and drink."

"Are the nurses kind to you?"

"That, they are, sir, kinder than I deserve."

"I have a message for you from No. -- on your corridor."

"No! have you, sir?"

"He sends his best wishes for your recovery."

"Now that is very good of him."

"And he would be very glad to hear from yourself how you feel."

"Well, sir, you tell him I am a trifle better, and God bless him for troubling his head about me."

In short, his reverence reversed the Hawes system. Under that a prisoner was divested of humanity and became a number and when he fell sick the sentiment created was, "The figure written on the floor of that cell looks faint." When he died or was murdered, "There is such and such a figure rubbed off our slate."

Mr. Eden made these figures signify flesh and blood, even to those who never saw their human faces. When he had softened a prisoner's heart then he laid the deeper truths of Christianity to that heart. They would not adhere to ice or stone or brass. He knew that till he had taught a man to love his brother whom he had seen he could never make him love God whom he has not seen. To vary the metaphor, his plan was, first warm and soften your wax then begin to shape it after Heaven's pattern. The old-fashioned way is freeze, petrify and mold your wax by a single process. Not that he was mawkish. No man rebuked sin more terribly than he often rebuked it in many of these cells; and when he did so see what he gained by the personal kindness that preceded these terrible rebukes! The rogue said: "What! is it so bad that his reverence, who I know has a regard for me, rebukes me for it like this?--why, it must be bad indeed!"

A loving friend's rebuke is a rebuke--sinks into the heart and convinces the judgment; an enemy's or stranger's rebuke is invective and irritates--not converts. The great vice of the new prisons is general self-deception varied by downright calculating hypocrisy. A shallow zealot like Mr. Lepel is sure to drive the prisoners into one or other of these. It was Mr. Eden's struggle to keep them out of it. He froze cant in the bud. Puritanical burglars tried Scriptural phrases on him as a matter of course, but they soon found it was the very worse lay they could get upon in ---- Jail. The notion that a man can jump from the depths of vice up to the climax of righteous habits, spiritual-mindedness, at one leap, shocked his sense and terrified him for the daring dogs that profess these saltatory powers and the geese that believe it. He said to such: "Let me see you crawl heavenward first, then walk heavenward; it will be time enough to soar when you have lived soberly, honestly, piously a year or two--not here, where you are tied hands, feet and tongue, but free among the world's temptations." He had no blind confidence in learned-by-heart texts. "Many a scoundrel has a good memory," said he.