ROSA fell ill with grief at the hotel, and could not move for some days; but the moment she was strong enough, she insisted on leaving Plymouth: like all wounded things, she must drag herself home.

But what a home! How empty it struck, and she heart-sick and desolate. Now all the familiar places wore a new aspect: the little yard, where he had so walked and waited, became a temple to her, and she came out and sat in it, and now first felt to the full how much he had suffered there--with what fortitude. She crept about the house, and kissed the chair he had sat in, and every much-used place and thing of the departed.

Her shallow nature deepened and deepened under this bereavement, of which, she said to herself, with a shudder, she was the cause. And this is the course of nature; there is nothing like suffering to enlighten the giddy brain, widen the narrow mind, improve the trivial heart.

As her regrets were tender and deep, so her vows of repentance were sincere. Oh, what a wife she would make when he came back! how thoughtful! how prudent! how loyal! and never have a secret. She who had once said, "What is the use of your writing? nobody will publish it," now collected and perused every written scrap. With simple affection she even locked up his very waste-paper basket, full of fragments he had torn, or useless papers he had thrown there, before he went to Plymouth.

In the drawer of his writing-table she found his diary. It was a thick quarto: it began with their marriage, and ended with his leaving home--for then he took another volume. This diary became her Bible; she studied it daily, till her tears hid his lines. The entries were very miscellaneous, very exact; it was a map of their married life. But what she studied most was his observations on her own character, so scientific, yet so kindly; and his scholar-like and wise reflections. The book was an unconscious picture of a great mind she had hitherto but glanced at: now she saw it all plain before her; saw it, understood it, adored it, mourned it. Such women are shallow, not for want of a head upon their shoulders, but of attention. They do not really study anything: they have been taught at their schools the bad art of skimming; but let their hearts compel their brains to think and think, the result is considerable. The deepest philosopher never fathomed a character more thoroughly than this poor child fathomed her philosopher, when she had read his journal ten or eleven times, and bedewed it with a thousand tears.

One passage almost cut her more intelligent heart in twain:--

"This dark day I have done a thing incredible. I have spoken with brutal harshness to the innocent creature I have sworn to protect. She had run in debt, through inexperience, and that unhappy timidity which makes women conceal an error till it ramifies, by concealment, into a fault; and I must storm and rave at her, till she actually fainted away. Brute! Ruffian! Monster! And she, how did she punish me, poor lamb? By soft and tender words--like a lady, as she is. Oh, my sweet Rosa, I wish you could know how you are avenged. Talk of the scourge--the cat! I would be thankful for two dozen lashes. Ah! there is no need, I think, to punish a man who has been cruel to a woman. Let him alone. He will punish himself more than you can, if he is really a man."

From the date of that entry, this self-reproach and self-torture kept cropping up every now and then in the diary; and it appeared to have been not entirely without its influence in sending Staines to sea, though the main reason he gave was that his Rosa might have the comforts and luxuries she had enjoyed before she married him.

One day, while she was crying over this diary, Uncle Philip called; but not to comfort her, I promise you. He burst on her, irate, to take her to task. He had returned, learned Christopher's departure, and settled the reason in his own mind: that uxorious fool was gone to sea, by a natural reaction; his eyes were open to his wife at last, and he was sick of her folly; so he had fled to distant climes, as who would not, that could?

"So, ma'am," said he, "my nephew is gone to sea, I find--all in a hurry. Pray may I ask what he has done that for?"

It was a very simple question, yet it did not elicit a very plain answer. She only stared at this abrupt inquisitor, and then cried, piteously, "Oh, Uncle Philip!" and burst out sobbing.

"Why, what is the matter?"

"You will hate me now. He is gone to make money for me; and I would rather have lived on a crust. Uncle--don't hate me. I'm a poor, bereaved, heart-broken creature, that repents."

"Repents! heigho! why, what have you been up to now, ma'am? No great harm, I'll be bound. Flirting a little with some fool--eh?"

"Flirting! Me! a married woman."

"Oh, to be sure; I forgot. Why, surely he has not deserted you."

"My Christopher desert me! He loves me too well; far more than I deserve; but not more than I will. Uncle Philip, I am too confused and wretched to tell you all that has happened; but I know you love him, though you had a tiff: uncle, he called on you, to shake hands and ask your forgiveness, poor fellow! He was so sorry you were away. Please read his dear diary: it will tell you all, better than his poor foolish wife can. I know it by heart. I'll show you where you and he quarrelled about me. There, see." And she showed him the passage with her finger. "He never told me it was that, or I would have come and begged your pardon on my knees. But see how sorry he was. There, see. And now I'll show you another place, where my Christopher speaks of your many, many acts of kindness. There, see. And now please let me show you how he longed for reconciliation. There, see. And it is the same through the book. And now I'll show you how grieved he was to go without your blessing. I told him I was sure you would give him that, and him going away. Ah, me! will he ever return? Uncle dear, don't hate me. What shall I do, now he is gone, if you disown me? Why, you are the only Staines left me to love."

"Disown you, ma'am! that I'll never do. You are a good-hearted young woman, I find. There, run and dry your eyes; and let me read Christopher's diary all through. Then I shall see how the land lies."

Rosa complied with his proposal; and left him alone while she bathed her eyes, and tried to compose herself, for she was all trembling at this sudden irruption.

When she returned to the drawing-room, he was walking about, looking grave and thoughtful.

"It is the old story," said he, rather gently: "a misunderstanding. How wise our ancestors were that first used that word to mean a quarrel! for, look into twenty quarrels, and you shall detect a score of mis-under-standings. Yet our American cousins must go and substitute the un-ideaed word 'difficulty'; that is wonderful. I had no quarrel with him: delighted to see either of you. But I had called twice on him; so I thought he ought to get over his temper, and call on a tried friend like me. A misunderstanding! Now, my dear, let us have no more of these misunderstandings. You will always be welcome at my house, and I shall often come here and look after you and your interests. What do you mean to do, I wonder?"

"Sir, I am to go home to my father, if he will be troubled with me. I have written to him."

"And what is to become of the Bijou?"

"My Christie thought I should like to part with it, and the furniture--but his own writing-desk and his chair, no, I never will, and his little clock. Oh! oh! oh!--But I remember what you said about agents, and I don't know what to do; for I shall be away."

"Then, leave it to me. I'll come and live here with one servant; and I'll soon sell it for you."

"You, Uncle Philip!"

"Well, why not?" said he roughly.

"That will be a great trouble and discomfort to you, I'm afraid."

"If I find it so, I'll soon drop it. I'm not the fool to put myself out for anybody. When you are ready to go out, send me word, and I'll come in."

Soon after this he bustled off. He gave her a sort of hurried kiss at parting, as if he was ashamed of it, and wanted it over as quickly as possible.

Next day her father came, condoled with her politely, assured her there was nothing to cry about; husbands were a sort of functionaries that generally went to sea at some part of their career, and no harm ever came of it. On the contrary, "Absence makes the heart grow fonder," said this judicious parent.

This sentiment happened to be just a little too true, and set the daughter crying bitterly. But she fought against it. "Oh no!" said she, "I mustn't. I will not be always crying in Kent Villa."

"Lord forbid!"

"I shall get over it in time--a little."

"Why, of course you will. But as to your coming to Kent Villa, I am afraid you would not be very comfortable there. You know I am superannuated. Only got my pension now."

"I know that, papa: and--why, that is one of the reasons. I have a good income now; and I thought if we put our means together--"

"Oh, that is a very different thing. You will want a carriage, I suppose. I have put mine down."

"No carriage; no horse; no footman; no luxury of any kind till my Christie comes back. I abhor dress; I abhor expense; I loathe everything I once liked too well; I detest every folly that has parted us; and I hate myself worst of all. Oh! oh! oh! Forgive me for crying so."

"Well, I dare say there are associations about this place that upset you. I shall go and make ready for you, dear; and then you can come as soon as you like."

He bestowed a paternal kiss on her brow, and glided doucely away before she could possibly cry again.

The very next week Rosa was at Kent Villa, with the relics of her husband about her; his chair, his writing-table, his clock, his waste-paper basket, a very deep and large one. She had them all in her bedroom at Kent Villa.

Here the days glided quietly but heavily.

She derived some comfort from Uncle Philip. His rough, friendly way was a tonic, and braced her. He called several times about the Bijou. Told her he had put up enormous boards all over the house, and puffed it finely. "I have had a hundred agents at me," said he; "and the next thing, I hope, will be one customer; that is about the proportion." At last he wrote her he had hooked a victim, and sold the lease and furniture for nine hundred guineas. Staines had assigned the lease to Rosa, so she had full powers; and Philip invested the money, and two hundred more she gave him, in a little mortgage at six per cent.

Now came the letter from Madeira. It gave her new life. Christopher was well, contented, hopeful. His example should animate her. She would bravely bear the present, and share his hopes of the future: with these brighter views Nature co-operated. The instincts of approaching maternity brightened the future. She fell into gentle reveries, and saw her husband return, and saw herself place their infant in his arms with all a wife's, a mother's pride.

In due course came another long letter from the equator, with a full journal, and more words of hope. Home in less than a year, with reputation increased by this last cure; home, to part no more.

Ah! what a changed wife he should find! how frugal, how candid, how full of appreciation, admiration, and love, of the noblest, dearest husband that ever breathed!

Lady Cicely Treherne waited some weeks, to let kinder sentiments return. She then called in Dear Street, but found Mrs. Staines was gone to Gravesend. She wrote to her.

In a few days she received a reply, studiously polite and cold.

This persistent injustice mortified her at last. She said to herself, "Does she think his departure was no loss to me? It was to her interests, as well as his, I sacrificed my own selfish wishes. I will write to her no more."

This resolution she steadily maintained. It was shaken for a moment, when she heard, by a side wind, that Mrs. Staines was fast approaching the great pain and peril of women. Then she wavered. But no. She prayed for her by name in the Liturgy, but she troubled her no more.

This state of things lasted some six weeks, when she received a letter from her cousin Tadcaster, close on the heels of his last, to which she had replied as I have indicated. She knew his handwriting, and opened it with a smile.

That smile soon died off her horror-stricken face. The letter ran thus:--

TRISTAN D'ACUNHA, Jan. 5.

DEAR CICELY,--A terrible thing has just happened. We signalled a raft, with a body on it, and poor Dr. Staines leaned out of the port-hole, and fell overboard. Three boats were let down after him; but it all went wrong, somehow, or it was too late. They could never find him, he was drowned; and the funeral service was read for the poor fellow.

We are all sadly cut up. Everybody loved him. It was dreadful next day at dinner, when his chair was empty. The very sailors cried at not finding him.

First of all, I thought I ought to write to his wife. I know where she lives; it is called Kent Villa, Gravesend. But I was afraid; it might kill her: and you are so good and sensible, I thought I had better write to you, and perhaps you could break it to her by degrees, before it gets in all the papers.

I send this from the island, by a small vessel, and paid him ten pounds to take it.

Your affectionate cousin,

TADCASTER.

Words are powerless to describe a blow like this: the amazement, the stupor, the reluctance to believe--the rising, swelling, surging horror. She sat like a woman of stone, crumpling the letter. "Dead!--dead?"

For a long time this was all her mind could realize--that Christopher Staines was dead. He who had been so full of life and thought and genius, and worthier to live than all the world, was dead; and a million nobodies were still alive, and he was dead.

She lay back on the sofa, and all the power left her limbs. She could not move a hand.

But suddenly she started up; for a noble instinct told her this blow must not fall on the wife as it had on her, and in her time of peril.

She had her bonnet on in a moment, and for the first time in her life, darted out of the house without her maid. She flew along the streets, scarcely feeling the ground. She got to Dear Street, and obtained Philip Staines's address. She flew to it, and there learned he was down at Kent Villa. Instantly she telegraphed to her maid to come down to her at Gravesend, with things for a short visit, and wait for her at the station; and she went down by train to Gravesend.

Hitherto she had walked on air, driven by one overpowering impulse. Now, as she sat in the train, she thought a little of herself. What was before her? To break to Mrs. Staines that her husband was dead. To tell her all her misgivings were more than justified. To encounter her cold civility, and let her know, inch by inch, it must be exchanged for curses and tearing of hair; her husband was dead. To tell her this, and in the telling of it, perhaps reveal that it was her great bereavement, as well as the wife's, for she had a deeper affection for him than she ought.

Well, she trembled like an aspen leaf, trembled like one in an ague, even as she sat. But she persevered.

A noble woman has her courage; not exactly the same as that which leads forlorn hopes against bastions bristling with rifles and tongued with flames and thunderbolts; yet not inferior to it.

Tadcaster, small and dull, but noble by birth and instinct, had seen the right thing for her to do; and she, of the same breed, and nobler far, had seen it too; and the great soul steadily drew the recoiling heart and quivering body to this fiery trial, this act of humanity--to do which was terrible and hard, to shirk it, cowardly and cruel.

She reached Gravesend, and drove in a fly to Kent Villa.

The door was opened by a maid.

"Is Mrs. Staines at home?"

"Yes, ma'am, she is at home: but--"

"Can I see her?"

"Why, no, ma'am, not at present."

"But I must see her. I am an old friend. Please take her my card. Lady Cicely Treherne."

The maid hesitated, and looked confused. "Perhaps you don't know, ma'am. Mrs. Staines, she is--the doctor have been in the house all day."

"Ah, the doctor! I believe Dr. Philip Staines is here."

"Why, that is the doctor, ma'am. Yes, he is here."

"Then, pray let me see him--or no; I had better see Mr. Lusignan."

"Master have gone out for the day, ma'am; but if you'll step in the drawing-room, I'll tell the doctor."

Lady Cicely waited in the drawing-room some time, heart-sick and trembling.

At last Dr. Philip came in, with her card in his hand, looking evidently a little cross at the interruption. "Now, madam, please tell me, as briefly as you can, what I can do for you."

"Are you Dr. Philip Staines?"

"I am, madam, at your service--for five minutes. Can't quit my patient long, just now."

"Oh, sir, thank God I have found you. Be prepared for ill news--sad news--a terrible calamity--I can't speak. Read that, sir." And she handed him Tadcaster's note.

He took it, and read it.

He buried his face in his hands. "Christopher! my poor, poor boy!" he groaned. But suddenly a terrible anxiety seized him. "Who knows of this?" he asked.

"Only myself, sir. I came here to break it to her."

"You are a good, kind lady, for being so thoughtful. Madam, if this gets to my niece's ears, it will kill her, as sure as we stand here."

"Then let us keep it from her. Command me, sir. I will do anything. I will live here--take the letters in--the journals--anything."

"No, no; you have done your part, and God bless you for it. You must not stay here. Your ladyship's very presence, and your agitation, would set the servants talking, and some idiot-fiend among them babbling--there is nothing so terrible as a fool."

"May I remain at the inn, sir; just one night?"

"Oh yes, I wish you would; and I will run over, if all is well with her--well with her? poor unfortunate girl!"

Lady Cicely saw he wished her gone, and she went directly.

At nine o'clock that same evening, as she lay on a sofa in the best room of the inn, attended by her maid, Dr. Philip Staines came to her. She dismissed her maid.

Dr. Philip was too old, in other words, had lost too many friends, to be really broken down by bereavement; but he was strangely subdued. The loud tones were out of him, and the loud laugh, and even the keen sneer. Yet he was the same man; but with a gentler surface; and this was not without its pathos.

"Well, madam," said he gravely and quietly. "It is as it always has been. 'As is the race of leaves, so that of man.' When one falls, another comes. Here's a little Christopher come, in place of him that is gone: a brave, beautiful boy, ma'am; the finest but one I ever brought into the world. He is come to take his father's place in our hearts--I see you valued his poor father, ma'am--but he comes too late for me. At your age, ma'am, friendships come naturally; they spring like loves in the soft heart of youth: at seventy, the gate is not so open; the soil is more sterile. I shall never care for another Christopher; never see another grow to man's estate."

"The mother, sir," sobbed Lady Cicely; "the poor mother?"

"Like them all--poor creature: in heaven, madam; in heaven. New life! new existence! a new character. All the pride, glory, rapture, and amazement of maternity--thanks to her ignorance, which we must prolong, or I would not give one straw for her life, or her son's. I shall never leave the house till she does know it, and come when it may, I dread the hour. She is not framed by nature to bear so deadly a shock."

"Her father, sir. Would he not be the best person to break it to her? He was out to-day."

"Her father, ma'am? I shall get no help from him. He is one of those soft, gentle creatures, that come into the world with what your canting fools call a mission; and his mission is to take care of number one. Not dishonestly, mind you, nor violently, nor rudely, but doucely and calmly. The care a brute like me takes of his vitals, that care Lusignan takes of his outer cuticle. His number one is a sensitive plant. No scenes, no noise; nothing painful--by-the-by, the little creature that writes in the papers, and calls calamities painful, is of Lusignan's breed. Out to-day! of course he was out, ma'am: he knew from me his daughter would be in peril all day, so he visited a friend. He knew his own tenderness, and evaded paternal sensibilities: a self-defender. I count on no help from that charming man."

"A man! I call such creachaas weptiles!" said Lady Cicely, her ghastly cheek coloring for a moment.

"Then you give them a false importance."

In the course of this interview, Lady Cicely accused herself sadly of having interfered between man and wife, and with the best intentions brought about this cruel calamity. "Judge, then, sir," said she, "how grateful I am to you for undertaking this cruel task. I was her schoolfellow, sir, and I love her dearly; but she has turned against me, and now, oh, with what horror she will regard me!"

"Madam," said the doctor, "there is nothing more mean and unjust than to judge others by events that none could foresee. Your conscience is clear. You did your best for my poor nephew: but Fate willed it otherwise. As for my niece, she has many virtues, but justice is one you must not look for in that quarter. Justice requires brains. It's a virtue the heart does not deal in. You must be content with your own good conscience, and an old man's esteem. You did all for the best; and this very day you have done a good, kind action. God bless you for it!"

Then he left her; and next day she went sadly home, and for many a long day the hollow world saw nothing of Cicely Treherne.

When Mr. Lusignan came home that night, Dr. Philip told him the miserable story, and his fears. He received it, not as Philip had expected. The bachelor had counted without his dormant paternity. He was terror-stricken--abject--fell into a chair, and wrung his hands, and wept piteously. To keep it from his daughter till she should be stronger, seemed to him chimerical, impossible. However, Philip insisted it must be done; and he must make some excuse for keeping out of her way, or his manner would rouse her suspicions. He consented readily to that, and indeed left all to Dr. Philip.

Dr. Philip trusted nobody; not even his own confidential servant. He allowed no journal to come into the house without passing through his hands, and he read them all before he would let any other soul in the house see them. He asked Rosa to let him be her secretary and open her letters, giving as a pretext that it would be as well she should have no small worries or trouble just now.

"Why," said she, "I was never so well able to bear them. It must be a great thing to put me out now. I am so happy, and live in the future. Well, dear uncle, you can if you like--what does it matter?--only there must be one exception: my own Christie's letters, you know."

"Of course," said he, wincing inwardly.

The very next day came a letter of condolence from Miss Lucas. Dr. Philip intercepted it, and locked it up, to be shown her at a more fitting time.

But how could he hope to keep so public a thing as this from entering the house in one of a hundred newspapers?

He went into Gravesend, and searched all the newspapers, to see what he had to contend with. To his horror, he found it in several dailies and weeklies, and in two illustrated papers. He sat aghast at the difficulty and the danger.

The best thing he could think of was to buy them all, and cut out the account. He did so, and brought all the papers, thus mutilated, into the house, and sent them into the kitchen. He said to his old servant, "These may amuse Mr. Lusignan's people, and I have extracted all that interests me."

By these means he hoped that none of the servants would go and buy more of these same papers elsewhere.

Notwithstanding these precautions, he took the nurse apart, and said, "Now, you are an experienced woman, and to be trusted about an excitable patient. Mind, I object to any female servant entering Mrs. Staines's room with gossip. Keep them outside the door for the present, please. Oh, and nurse, if anything should happen, likely to grieve or to worry her, it must be kept from her entirely: can I trust you?"

"You may, sir."

"I shall add ten guineas to your fee, if she gets through the month without a shock or disturbance of any kind."

She stared at him, inquiringly. Then she said,--

"You may rely on me, doctor."

"I feel I may. Still, she alarms me. She looks quiet enough, but she is very excitable."

Not all these precautions gave Dr. Philip any real sense of security; still less did they to Mr. Lusignan. He was not a tender father, in small things, but the idea of actual danger to his only child was terrible to him and he now passed his life in a continual tremble.

This is the less to be wondered at, when I tell you that even the stout Philip began to lose his nerve, his appetite, his sleep, under this hourly terror and this hourly torture.

Well did the great imagination of antiquity feign a torment, too great for the mind long to endure, in the sword of Damocles suspended by a single hair over his head. Here the sword hung over an innocent creature, who smiled beneath it, fearless; but these two old men must sit and watch the sword, and ask themselves how long before that subtle salvation shall snap.

"Ill news travels fast," says the proverb. "The birds of the air shall carry the matter," says Holy Writ; and it is so. No bolts nor bars, no promises nor precautions, can long shut out a great calamity from the ears it is to blast, the heart it is to wither. The very air seems full of it, until it falls.

Rosa's child was more than a fortnight old; and she was looking more beautiful than ever, as is often the case with a very young mother, and Dr. Philip complimented her on her looks. "Now," said he, "you reap the advantage of being good, and obedient, and keeping quiet. In another ten days or so, I may take you to the seaside for a week. I have the honor to inform you that from about the fourth to the tenth of March there is always a week of fine weather, which takes everybody by surprise, except me. It does not astonish me, because I observe it is invariable. Now, what would you say if I gave you a week at Herne Bay, to set you up altogether?"

"As you please, dear uncle," said Mrs. Staines, with a sweet smile. "I shall be very happy to go, or to stay. I shall be happy everywhere, with my darling boy, and the thought of my husband. Why, I count the days till he shall come back to me. No, to us; to us, my pet. How dare a naughty mammy say to 'me,' as if 'me' was half the 'portance of oo, a precious pets!"

Dr. Philip was surprised into a sigh.

"What is the matter, dear?" said Rosa, very quickly.

"The matter?"

"Yes, dear, the matter. You sighed; you, the laughing philosopher."

"Did I?" said he, to gain time. "Perhaps I remembered the uncertainty of human life, and of all mortal hopes. The old will have their thoughts, my dear. They have seen so much trouble."

"But, uncle dear, he is a very healthy child."

"Very."

"And you told me yourself carelessness was the cause so many children die."

"That is true."

She gave him a curious and rather searching look; then, leaning over her boy, said, "Mammy's not afraid. Beautiful Pet was not born to die directly. He will never leave his mam-ma. No, uncle, he never can. For my life is bound in his and his dear father's. It is a triple cord: one go, go all."

She said this with a quiet resolution that chilled Uncle Philip.

At this moment the nurse, who had been bending so pertinaciously over some work that her eyes were invisible, looked quickly up, cast a furtive glance at Mrs. Staines, and finding she was employed for the moment, made an agitated signal to Dr. Philip. All she did was to clench her two hands and lift them half way to her face, and then cast a frightened look towards the door; but Philip's senses were so sharpened by constant alarm and watching, that he saw at once something serious was the matter. But as he had asked himself what he should do in case of some sudden alarm, he merely gave a nod of intelligence to the nurse, scarcely perceptible, then rose quietly from his seat, and went to the window. "Snow coming, I think," said he. "For all that we shall have the March summer in ten days. You mark my words." He then went leisurely out of the room; at the door he turned, and, with all the cunning he was master of, said, "Oh, by the by, come to my room, nurse, when you are at leisure."

"Yes, doctor," said the nurse, but never moved. She was too bent on hiding the agitation she really felt.

"Had you not better go to him, nurse?"

"Perhaps I had, madam."

She rose with feigned indifference, and left the room. She walked leisurely down the passage, then, casting a hasty glance behind her, for fear Mrs. Staines should be watching her, hurried into the doctor's room. They met at once in the middle of the room, and Mrs. Briscoe burst out, "Sir, it is known all over the house!"

"Heaven forbid! What is known?"

"What you would give the world to keep from her. Why, sir, the moment you cautioned me, of course I saw there was trouble. But little I thought--sir, not a servant in the kitchen or the stable but knows that her husband--poor thing! poor thing!--Ah! there goes the housemaid--to have a look at her."

"Stop her!"

Mrs. Briscoe had not waited for this; she rushed after the woman, and told her Mrs. Staines was sleeping, and the room must not be entered on any account.

"Oh, very well," said the maid, rather sullenly.

Mrs. Briscoe saw her return to the kitchen, and came back to Dr. Staines; he was pacing the room in torments of anxiety.

"Doctor," said she, "it is the old story: 'Servants' friends, the master's enemies.' An old servant came here to gossip with her friend the cook (she never could abide her while they were together, by all accounts), and told her the whole story of his being drowned at sea."

Dr. Philip groaned, "Cursed chatterbox!" said he. "What is to be done? Must we break it to her now? Oh, if I could only buy a few days more! The heart to be crushed while the body is weak! It is too cruel. Advise me, Mrs. Briscoe. You are an experienced woman, and I think you are a kind-hearted woman."

"Well, sir," said Mrs. Briscoe, "I had the name of it, when I was younger--before Briscoe failed, and I took to nursing; which it hardens, sir, by use, and along of the patients themselves; for sick folk are lumps of selfishness; we see more of them than you do, sir. But this I will say, 'tisn't selfishness that lies now in that room, waiting for the blow that will bring her to death's door, I'm sore afraid; but a sweet, gentle, thoughtful creature, as ever supped sorrow; for I don't know how 'tis, doctor, nor why 'tis, but an angel like that has always to sup sorrow."

"But you do not advise me," said the doctor, in agitation, "and something must be done."

"Advise you, sir; it is not for me to do that. I am sure I'm at my wits' ends, poor thing! Well, sir, I don't see what you can do, but try and break it to her. Better so, than let it come to her like a clap of thunder. But I think, sir, I'd have a wet-nurse ready, before I said much: for she is very quick--and ten to one but the first word of such a thing turns her blood to gall. Sir, I once knew a poor woman--she was a carpenter's wife--a-nursing her child in the afternoon--and in runs a foolish woman, and tells her he was killed dead, off a scaffold. 'Twas the man's sister told her. Well, sir, she was knocked stupid like, and she sat staring, and nursing of her child, before she could take it in rightly. The child was dead before supper-time, and the woman was not long after. The whole family was swept away, sir, in a few hours, and I mind the table was not cleared he had dined on, when they came to lay them out. Well-a-day, nurses see sorrow!"

"We all see sorrow that live long, Mrs. Briscoe. I am heart-broken myself; I am desperate. You are a good soul, and I'll tell you. When my nephew married this poor girl, I was very angry with him; and I soon found she was not fit to be a struggling man's wife; and then I was very angry with her. She had spoiled a first-rate physician, I thought. But, since I knew her better, it is all changed. She is so lovable. How I shall ever tell her this terrible thing, God knows. All I know is, that I will not throw a chance away. Her body shall be stronger, before I break her heart. Cursed idiots, that could not save a single man, with their boats, in a calm sea! Lord forgive me for blaming people, when I was not there to see. I say I will give her every chance. She shall not know it till she is stronger: no, not if I live at her door, and sleep there, and all. Good God! inspire me with something. There is always something to be done, if one could but see it."

Mrs. Briscoe sighed and said, "Sir, I think anything is better than for her to hear it from a servant--and they are sure to blurt it out. Young women are such fools."

"No, no; I see what it is," said Dr. Philip. "I have gone all wrong from the first. I have been acting like a woman, when I should have acted like a man. Why, I only trusted you by halves. There was a fool for you. Never trust people by halves."

"That is true, sir."

"Well, then, now I shall go at it like a man. I have a vile opinion of servants; but no matter. I'll try them: they are human, I suppose. I'll hit them between the eyes like a man. Go to the kitchen, Mrs. Briscoe, and tell them I wish to speak to all the servants, indoors or out."

"Yes, sir."

She stopped at the door, and said, "I had better get back to her, as soon as I have told them."

"Certainly."

"And what shall I tell her, sir? Her first word will be to ask me what you wanted me for. I saw that in her eye. She was curious: that is why she sent me after you so quick."

Dr. Philip groaned. He felt he was walking among pitfalls. He rapidly flavored some distilled water with orange-flower, then tinted it a beautiful pink, and bottled it. "There," said he; "I was mixing a new medicine. Tablespoon, four times a day: had to filter it. Any lie you like."

Mrs. Briscoe went to the kitchen, and gave her message: then went to Mrs. Staines with the mixture.

Dr. Philip went down to the kitchen, and spoke to the servants very solemnly. He said, "My good friends, I am come to ask your help in a matter of life and death. There is a poor young woman up-stairs; she is a widow, and does not know it; and must not know it yet. If the blow fell now, I think it would kill her: indeed, if she hears it all of a sudden, at any time, that might destroy her. We are in so sore a strait that a feather may turn the scale. So we must try all we can to gain a little time, and then trust to God's mercy after all. Well, now, what do you say? Will you help me keep it from her, till the tenth of March, say? and then I will break it to her by degrees. Forget she is your mistress. Master and servant, that is all very well at a proper time; but this is the time to remember nothing but that we are all one flesh and blood. We lie down together in the churchyard, and we hope to rise together where there will be no master and servant. Think of the poor unfortunate creature as your own flesh and blood, and tell me, will you help me try and save her, under this terrible blow?"

"Ay, doctor, that we will," said the footman. "Only you give us our orders, and you will see."

"I have no right to give you orders; but I entreat you not to show her by word or look, that calamity is upon her. Alas! it is only a reprieve you can give her and to me. The bitter hour must come when I must tell her she is a widow, and her boy an orphan. When that day comes, I will ask you all to pray for me that I may find words. But now I ask you to give me that ten days' reprieve. Let the poor creature recover a little strength, before the thunderbolt of affliction falls on her head. Will you promise me?"

They promised heartily; and more than one of the women began to cry.

"A general assent will not satisfy me," said Dr. Philip. "I want every man, and every woman, to give me a hand upon it; then I shall feel sure of you."

The men gave him their hands at once. The women wiped their hands with their aprons, to make sure they were clean, and gave him their hands too. The cook said, "If any one of us goes from it, this kitchen will be too hot to hold her."

"Nobody will go from it, cook," said the doctor. "I'm not afraid of that; and now since you have promised me, out of your own good hearts, I'll try and be even with you. If she knows nothing of it by the tenth of March, five guineas to every man and woman in this kitchen. You shall see that, if you can be kind, we can be grateful."

He then hurried away. He found Mr. Lusignan in the drawing-room, and told him all this. Lusignan was fluttered, but grateful. "Ah, my good friend," said he, "this is a hard trial to two old men, like you and me."

"It is," said Philip. "It has shown me my age. I declare I am trembling; I, whose nerves were iron. But I have a particular contempt for servants. Mercenary wretches! I think Heaven inspired me to talk to them. After all, who knows? perhaps we might find a way to their hearts, if we did not eternally shock their vanity, and forget that it is, and must be, far greater than our own. The women gave me their tears, and the men were earnest. Not one hand lay cold in mine. As for your kitchen-maid, I'd trust my life to that girl. What a grip she gave me! What strength! What fidelity was in it! My hand was never grasped before. I think we are safe for a few days more."

Lusignan sighed. "What does it all come to? We are pulling the trigger gently, that is all."

"No, no; that is not it. Don't let us confound the matter with similes, please. Keep them for children."

Mrs. Staines left her bed; and would have left her room, but Dr. Philip forbade it strictly.

One day, seated in her arm-chair, she said to the nurse, before Dr. Philip, "Nurse, why do the servants look so curiously at me?"

Mrs. Briscoe cast a hasty glance at Dr. Philip, and then said, "I don't know, madam. I never noticed that."

"Uncle, why did nurse look at you before she answered such a simple question?"

"I don't know. What question?"

"About the servants."

"Oh, about the servants!" said he contemptuously.

"You should not turn up your nose at them, for they are all most kind and attentive. Only, I catch them looking at me so strangely; really--as if they--"

"Rosa, you are taking me quite out of my depth. The looks of servant girls! Why, of course a lady in your condition is an object of especial interest to them. I dare say they are saying to one another, 'I wonder when my turn will come!' A fellow-feeling makes us wondrous kind--that is a proverb, is it not?"

"To be sure. I forgot that."

She said no more; but seemed thoughtful, and not quite satisfied.

On this Dr. Philip begged the maids to go near her as little as possible. "You are not aware of it," said he, "but your looks, and your manner of speaking, rouse her attention, and she is quicker than I thought she was, and observes very subtly."

This was done; and then she complained that nobody came near her. She insisted on coming down-stairs; it was so dull.

Dr. Philip consented, if she would be content to receive no visits for a week.

She assented to that; and now passed some hours every day in the drawing-room. In her morning wrappers, so fresh and crisp, she looked lovely, and increased in health and strength every day.

Dr. Philip used to look at her, and his very flesh would creep at the thought that, ere long, he must hurl this fair creature into the dust of affliction; must, with a word, take the ruby from her lips, the rose from her cheeks, the sparkle from her glorious eyes--eyes that beamed on him with sweet affection, and a mouth that never opened, but to show some simplicity of mind, or some pretty burst of the sensitive heart.

He put off, and put off, and at last cowardice began to whisper, "Why tell her the whole truth at all? Why not take her through stages of doubt, alarm, and, after all, leave a grain of hope till her child gets so rooted in her heart that--" But conscience and good sense interrupted this temporary thought, and made him see to what a horrible life of suspense he should condemn a human creature, and live a perpetual lie, and be always at the edge of some pitfall or other.

One day, while he sat looking at her, with all these thoughts, and many more, coursing through his mind, she looked up at him, and surprised him. "Ah!" said she gravely.

"What is the matter, my dear?"

"Oh, nothing," said she cunningly.

"Uncle, dear," said she presently, "when do we go to Herne Bay?"

Now, Dr. Philip had given that up. He had got the servants at Kent Villa on his side, and he felt safer here than in any strange place: so he said, "I don't know: that all depends. There is plenty of time."

"No, uncle," said Rosa gravely. "I wish to leave this house. I can hardly breathe in it."

"What! your native air?"

"Mystery is not my native air; and this house is full of mystery. Voices whisper at my door, and the people don't come in. The maids cast strange looks at me, and hurry away. I scolded that pert girl Jane, and she answered me as meek as Moses. I catch you looking at me, with love, and something else. What is that something--? It is Pity: that is what it is. Do you think, because I am called a simpleton, that I have no eyes, nor ears, nor sense? What is this secret which you are all hiding from one person, and that is me? Ah! Christopher has not written these five weeks. Tell me the truth, for I will know it," and she started up in wild excitement.

Then Dr. Philip saw the hour was come.

He said, "My poor girl, you have read us right. I am anxious about Christopher, and all the servants know it."

"Anxious, and not tell me; his wife; the woman whose life is bound up in his."

"Was it for us to retard your convalescence, and set you fretting, and perhaps destroy your child? Rosa, my darling, think what a treasure Heaven has sent you, to love and care for."

"Yes," said she, trembling, "Heaven has been good to me; I hope Heaven will always be as good to me. I don't deserve it; but then I tell God so. I am very grateful, and very penitent. I never forget that, if I had been a good wife, my husband--five weeks is a long time. Why do you tremble so? Why are you so pale--a strong man like you? Calamity! Calamity!"

Dr. Philip hung his head.

She looked at him, started wildly up, then sank back into her chair. So the stricken deer leaps, then falls. Yet even now she put on a deceitful calm, and said, "Tell me the truth. I have a right to know."

He stammered out, "There is a report of an accident at sea."

She kept silence.

"Of a passenger drowned--out of that ship. This, coupled with his silence, fills our hearts with fear."

"It is worse--you are breaking it to me--you have gone too far to stop. One word: is he alive? Oh, say he is alive!"

Philip rang the bell hard, and said in a troubled voice, "Rosa, think of your child."

"Not when my husband-- Is he alive or dead?"

"It is hard to say, with such a terrible report about, and no letters," faltered the old man, his courage failing him.

"What are you afraid of? Do you think I can't die, and go to him? Alive, or dead?" and she stood before him, raging and quivering in every limb.

The nurse came in.

"Fetch her child," he cried; "God have mercy on her."

"Ah, then he is dead," said she, with stony calmness. "I drove him to sea, and he is dead."

The nurse rushed in, and held the child to her.

She would not look at it.

"Dead!"

"Yes, our poor Christie is gone--but his child is here--the image of him. Do not forget the mother. Have pity on his child and yours."

"Take it out of my sight!" she screamed. "Away with it, or I shall murder it, as I have murdered its father. My dear Christie, before all that live! I have killed him. I shall die for him. I shall go to him." She raved and tore her hair. Servants rushed in. Rosa was carried to her bed, screaming and raving, and her black hair all down on both sides, a piteous sight.

Swoon followed swoon, and that very night brain fever set in with all its sad accompaniments; a poor bereaved creature, tossing and moaning; pale, anxious, but resolute faces of the nurse and the kitchen-maid watching: on one table a pail of ice, and on another the long, thick raven hair of our poor Simpleton, lying on clean silver paper. Dr. Philip had cut it all off with his own hand, and he was now folding it up, and crying over it; for he thought to himself, "Perhaps in a few days more only this will be left of her on earth."

STAINES fell head-foremost into the sea with a heavy plunge. Being an excellent swimmer, he struck out the moment he touched the water, and that arrested his dive, and brought him up with a slant, shocked and panting, drenched and confused. The next moment he saw, as through a fog--his eyes being full of water--something fall from the ship. He breasted the big waves, and swam towards it: it rose on the top of a wave, and he saw it was a life-buoy. Encumbered with wet clothes, he seemed impotent in the big waves; they threw him up so high, and down so low.

Almost exhausted, he got to the life-buoy, and clutched it with a fierce grasp and a wild cry of delight. He got it over his head, and, placing his arms round the buoyant circle, stood with his breast and head out of water, gasping.

He now drew a long breath, and got his wet hair out of his eyes, already smarting with salt water, and, raising himself on the buoy, looked out for help.

He saw, to his great concern, the ship already at a distance. She seemed to have flown, and she was still drifting fast away from him.

He saw no signs of help. His heart began to turn as cold as his drenched body. A horrible fear crossed him.

But presently he saw the weather-boat filled, and fall into the water; and then a wave rolled between him and the ship, and he only saw her topmast.

The next time he rose on a mighty wave he saw the boats together astern of the vessel, but not coming his way; and the gloom was thickening, the ship becoming indistinct, and all was doubt and horror.

A life of agony passed in a few minutes.

He rose and fell like a cork on the buoyant waves--rose and fell, and saw nothing but the ship's lights, now terribly distant.

But at last, as he rose and fell, he caught a few fitful glimpses of a smaller light rising and falling like himself. "A boat!" he cried, and raising himself as high as he could, shouted, cried, implored for help. He stretched his hands across the water. "This way! this way!"

The light kept moving, but it came no nearer. They had greatly underrated the drift. The other boat had no light.

Minutes passed of suspense, hope, doubt, dismay, terror. Those minutes seemed hours.

In the agony of suspense the quaking heart sent beads of sweat to the brow, though the body was immersed.

And the gloom deepened, and the cold waves flung him up to heaven with their giant arms, and then down again to hell: and still that light, his only hope, was several hundred yards from him.

Only for a moment at a time could his eyeballs, straining with agony, catch this will-o'-the-wisp, the boat's light. It groped the sea up and down, but came no nearer.

When what seemed days of agony had passed, suddenly a rocket rose in the horizon--so it seemed to him.

The lost man gave a shriek of joy; so prone are we to interpret things hopefully.

Misery! The next time he saw that little light, that solitary spark of hope, it was not quite so near as before. A mortal sickness fell on his heart. The ship had recalled the boats by rocket.

He shrieked, he cried, he screamed, he raved. "Oh, Rosa! Rosa! for her sake, men, men, do not leave me. I am here! here!"

In vain. The miserable man saw the boat's little light retire, recede, and melt into the ship's larger light, and that light glided away.

Then, a cold, deadly stupor fell on him. Then, death's icy claw seized his heart, and seemed to run from it to every part of him. He was a dead man. Only a question of time. Nothing to gain by floating.

But the despairing mind could not quit the world in peace, and even here in the cold, cruel sea, the quivering body clung to this fragment of life, and winced at death's touch, though more merciful.

He despised this weakness; he raged at it; he could not overcome it.

Unable to live or to die, condemned to float slowly, hour by hour, down into death's jaws.

To a long, death-like stupor succeeded frenzy. Fury seized this great and long-suffering mind. It rose against the cruelty and injustice of his fate. He cursed the world, whose stupidity had driven him to sea, he cursed remorseless nature; and at last he railed on the God who made him, and made the cruel water, that was waiting for his body. "God's justice! God's mercy! God's power! they are all lies," he shouted, "dreams, chimeras, like Him the all-powerful and good, men babble of by the fire. If there was a God more powerful than the sea, and only half as good as men are, he would pity my poor Rosa and me, and send a hurricane to drive those caitiffs back to the wretch they have abandoned. Nature alone is mighty. Oh, if I could have her on my side, and only God against me! But she is as deaf to prayer as He is: as mechanical and remorseless. I am a bubble melting into the sea. Soul I have none; my body will soon be nothing, nothing. So ends an honest, loving life. I always tried to love my fellow-creatures. Curse them! curse them! Curse the earth! Curse the sea! Curse all nature: there is no other God for me to curse."

The moon came out.

He raised his head and staring eyeballs, and cursed her.

The wind began to whistle, and flung spray in his face.

He raised his fallen head and staring eyeballs, and cursed the wind.

While he was thus raving, he became sensible of a black object to windward.

It looked like a rail, and a man leaning on it.

He stared, he cleared the wet hair from his eyes, and stared again.

The thing, being larger than himself and partly out of water, was drifting to leeward faster than himself.

He stared and trembled, and at last it came nearly abreast, black, black.

He gave a loud cry, and tried to swim towards it; but encumbered with his life-buoy, he made little progress. The thing drifted abreast of him, but ten yards distant.

As they each rose high upon the waves, he saw it plainly.

It was the very raft that had been the innocent cause of his sad fate.

He shouted with hope, he swam, he struggled; he got near it, but not to it; it drifted past, and he lost his chance of intercepting it. He struggled after it. The life-buoy would not let him catch it.

Then he gave a cry of agony, rage, despair, and flung off the life-buoy, and risked all on this one chance.

He gains a little on the raft.

He loses.

He gains: he cries, "Rosa! Rosa!" and struggles with all his soul, as well as his body: he gains.

But when almost within reach, a wave half drowns him, and he loses.

He cries, "Rosa! Rosa!" and swims high and strong. "Rosa! Rosa! Rosa!"

He is near it. He cries, "Rosa! Rosa!" and with all the energy of love and life flings himself almost out of the water, and catches hold of the nearest thing on the raft.

It was the dead man's leg.

It seemed as if it would come away in his grasp. He dared not try to pull himself up by that. But he held on by it, panting, exhausting, faint.

This faintness terrified him. "Oh," thought he, "if I faint now, all is over."

Holding by that terrible and strange support, he made a grasp, and caught hold of the woodwork at the bottom of the rail. He tried to draw himself up. Impossible.

He was no better off than with his life-buoy.

But in situations so dreadful, men think fast; he worked gradually round the bottom of the raft by his hands, till he got to leeward, still holding on. There he found a solid block of wood at the edge of the raft. He prised himself carefully up; the raft in that part then sank a little: he got his knee upon the timber of the raft, and with a wild cry seized the nearest upright, and threw both arms round it and clung tight. Then first he found breath to speak. "THANK GOD!" he cried, kneeling on the timber, and grasping the upright post--"OH, THANK GOD! THANK GOD!"

"THANK GOD?" why, according to his theory, it should have been "Thank Nature." But I observe that, in such cases, even philosophers are ungrateful to the mistress they worship.

Our philosopher not only thanked God, but being on his knees, prayed forgiveness for his late ravings, prayed hard, with one arm curled round the upright, lest the sea, which ever and anon rushed over the bottom of the raft, should swallow him up in a moment.

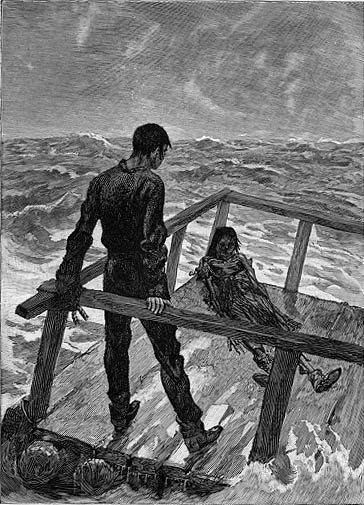

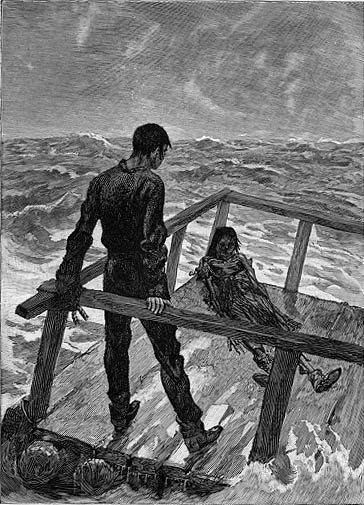

Then he rose carefully, and wedged himself into the corner of the raft opposite to that other figure, ominous relic of the wild voyage the new-comer had entered upon; he put both arms over the rail, and stood erect.

The moon was now up; but so was the breeze: fleecy clouds flew with vast rapidity across her bright face, and it was by fitful though vivid glances Staines examined the raft and his companion.

The raft was large, and well made of timbers tied and nailed together, and a strong rail ran round it resting on several uprights. There were also some blocks of a very light wood screwed to the horizontal timbers, and these made it float high.

But what arrested and fascinated the man's gaze was his dead companion, sole survivor, doubtless, of a horrible voyage, since the raft was not made for one, nor by one.

It was a skeleton, or nearly, whose clothes the seabirds had torn, and pecked every limb in all the fleshy parts; the rest of the body had dried to dark leather on the bones. The head was little more than an eyeless skull; but in the fitful moonlight, those huge hollow caverns seemed gigantic lamp-like eyes, and glared at him fiendishly, appallingly.

He sickened at the sight. He tried not to look at it; but it would be looked at, and threaten him in the moonlight, with great lack-lustre eyes.

The wind whistled, and lashed his face with spray torn off the big waves, and the water was nearly up to his knees, and the raft tossed so wildly, it was all he could do to hold on in his corner: in which struggle, still those monstrous lack-lustre eyes, like lamps of death, glared at him in the moon; all else was dark, except the fiery crests of the black mountain-billows, tumbling and raging all around.

What a night!

But, before morning, the breeze sank, the moon set, and a sombre quiet succeeded, with only that grim figure in outline dimly visible. Owing to the motion still retained by the waves, it seemed to nod and rear, and be ever preparing to rush upon him.

The sun rose glorious, on a lovely scene; the sky was a very mosaic of colors sweet and vivid, and the tranquil, rippling sea, peach-colored to the horizon, with lines of diamonds where the myriad ripples broke into smiles.

Staines was asleep, exhausted. Soon the light awoke him, and he looked up. What an incongruous picture met his eye: that heaven of color all above and around, and right before him, like a devil stuck in mid-heaven, that grinning corpse, whose fate foreshadowed his own.

But daylight is a great strengthener of the nerves; the figure no longer appalled him--a man who had long learned to look with Science's calm eye upon the dead. When the sea became like glass, and from peach-color deepened to rose, he walked along the raft, and inspected the dead man. He found it was a man of color, but not a black. The body was not kept in its place, as he had supposed, merely by being jammed into the angle caused by the rail; it was also lashed to the corner upright by a long, stout belt. Staines concluded this had kept the body there, and its companions had been swept away.

This was not lost on him: he removed the belt for his own use: he then found it was not only a belt, but a receptacle; it was nearly full of small, hard substances that felt like stones.

When he had taken it off the body, he felt a compunction. "Ought he to rob the dead, and expose it to be swept into the sea at the first wave, like a dead dog?"

He was about to replace the belt, when a middle course occurred to him. He was a man who always carried certain useful little things about him, viz., needles, thread, scissors, and string. He took a piece of string, and easily secured this poor light skeleton to the raft. The belt he strapped to the rail, and kept for his own need.

And now hunger gnawed him. No food was near. There was nothing but the lovely sea and sky, mosaic with color, and that grim, ominous skeleton.

Hunger comes and goes many times before it becomes insupportable. All that day and night, and the next day, he suffered its pangs; and then it became torture, but the thirst maddening.

Towards night fell a gentle rain. He spread a handkerchief and caught it. He sucked the handkerchief.

This revived him, and even allayed in some degree the pangs of hunger.

Next day was cloudless. A hot sun glared on his unprotected head, and battered down his enfeebled frame.

He resisted as well as he could. He often dipped his head, and as often the persistent sun, with cruel glare, made it smoke again.

Next day the same: but the strength to meet it was waning. He lay down and thought of Rosa, and wept bitterly. He took the dead man's belt, and lashed himself to the upright. That act, and his tears for his beloved, were almost his last acts of perfect reason: for next day came the delusions and the dreams that succeed when hunger ceases to torture, and the vital powers begin to ebb. He lay and saw pleasant meadows with meandering streams, and clusters of rich fruit that courted the hand and melted in the mouth.

Ever and anon they vanished, and he saw grim death looking down on him with those big cavernous eyes.

By and by, whether his body's eye saw the grim skeleton, or his mind's eye the juicy fruits, green meadows, and pearly brooks, all was shadowy.

So, in a placid calm, beneath a blue sky, the raft drifted dead, with its dead freight, upon the glassy purple, and he drifted, too, towards the world unknown.

There came across the waters to that dismal raft a thing none too common, by sea or land--a good man.

He was tall, stalwart, bronzed, and had hair like snow, before his time, for he had known trouble. He commanded a merchant steamer, bound for Calcutta, on the old route.

The man at the mast-head descried a floating wreck, and hailed the deck accordingly. The captain altered his course without one moment's hesitation, and brought up alongside, lowered a boat, and brought the dead, and the breathing man, on board.

A young middy lifted Staines in his arms from the wreck to the boat; he whose person I described in Chapter I. weighed now no more than that.

Men are not always rougher than women. Their strength and nerve enable them now and then to be gentler than buttery-fingered angels, who drop frail things through sensitive agitation, and break them. These rough men saw Staines was hovering between life and death, and they handled him like a thing the ebbing life might be shaken out of in a moment. It was pretty to see how gingerly the sailors carried the sinking man up the ladder, and one fetched swabs, and the others laid him down softly on them at their captain's feet.

"Well done, men," said he. "Poor fellow! Pray Heaven, we may not have come too late. Now stand aloof a bit. Send the surgeon aft."

The surgeon came, and looked, and felt the heart. He shook his head, and called for brandy. He had Staines's head raised, and got half a spoonful of diluted brandy down his throat. But there was an ominous gurgling.

After several such attempts at intervals, he said plainly the man's life could not be saved by ordinary means.

"Then try extraordinary," said the captain. "My orders are that he is to be saved. There is life in him. You have only got to keep it there. He must be saved; he shall be saved."

"I should like to try Dr. Staines's remedy," said the surgeon.

"Try it, then what is it?"

"A bath of beef-tea. Dr. Staines says he applied it to a starved child--in the Lancet."

"Take a hundred-weight of beef, and boil it in the coppers."

Thus encouraged, the surgeon went to the cook, and very soon beef was steaming on a scale and at a rate unparalleled.

Meantime, Captain Dodd had the patient taken to his own cabin, and he and his servant administered weak brandy and water with great caution and skill.

There was no perceptible result. But at all events there was life and vital instinct left, or he could not have swallowed.

Thus they hovered about him for some hours, and then the bath was ready.

The captain took charge of the patient's clothes: the surgeon and a sailor bathed him in lukewarm beef-tea, and then covered him very warm with blankets next the skin. Guess how near a thing it seemed to them, when I tell you they dared not rub him.

Just before sunset his pulse became perceptible. The surgeon administered half a spoonful of egg-flip. The patient swallowed it.

By and by he sighed.

"He must not be left, day or night," said the captain. "I don't know who or what he is, but he is a man; and I could not bear him to die now."

That night Captain Dodd overhauled the patient's clothes, and looked for marks on his linen. There were none.

"Poor devil," said Captain Dodd. "He is a bachelor."

Captain Dodd found his pocket-book, with bank-notes, £200. He took the numbers, made a memorandum of them, and locked the notes up.

He lighted his lamp, examined the belt, unripped it, and poured out the contents on his table.

They were dazzling. A great many large pieces of amethyst, and some of white topaz and rock crystal; a large number of smaller stones, carbuncles, chrysolites, and not a few emeralds. Dodd looked at them with pleasure, sparkling in the lamplight.

"What a lot!" said he. "I wonder what they are worth!" He sent for the first mate, who, he knew, did a little private business in precious stones. "Masterton," said he, "oblige me by counting these stones with me, and valuing them."

Mr. Masterton stared, and his mouth watered. However, he named the various stones and valued them. He said there was one stone, a large emerald, without a flaw, that was worth a heavy sum by itself; and the pearls, very fine: and looking at the great number, they must be worth a thousand pounds.

Captain Dodd then entered the whole business carefully in the ship's log: the living man he described thus: "About five feet six in height, and about fifty years of age." Then he described the notes and the stones very exactly, and made Masterton, the valuer, sign the log.

Staines took a good deal of egg-flip that night, and next day ate solid food; but they questioned him in vain; his reason was entirely in abeyance: he had become an eater, and nothing else. Whenever they gave him food, he showed a sort of fawning animal gratitude. Other sentiment he had none, nor did words enter his mind any more than a bird's. And since it is not pleasant to dwell on the wreck of a fine understanding, I will only say that they landed him at Cape Town, out of bodily danger, but weak, and his mind, to all appearance, a hopeless blank.

They buried the skeleton,--read the service of the English Church over a Malabar heathen.

Dodd took Staines to the hospital, and left twenty pounds with the governor of it to cure him. But he deposited Staines's money and jewels with a friendly banker, and begged that the principal cashier might see the man, and be able to recognize him, should he apply for his own.

The cashier came and examined him, and also the ruby ring on his finger--a parting gift from Rosa--and remarked this was a new way of doing business.

"Why, it is the only one, sir," said Dodd. "How can we give you his signature? He is not in his right mind."

"Nor never will be."

"Don't say that, sir. Let us hope for the best, poor fellow."

Having made these provisions, the worthy captain weighed anchor, with a warm heart and a good conscience. Yet the image of the man he had saved pursued him, and he resolved to look after him next time he should coal at Cape Town, homeward bound.

Staines recovered his strength in about two months; but his mind returned in fragments, and very slowly. For a long, long time he remembered nothing that had preceded his great calamity. His mind started afresh, aided only by certain fixed habits; for instance, he could read and write: but, strange as it may appear, he had no idea who he was; and when his memory cleared a little on that head, he thought his surname was Christie, but he was not sure.

Nevertheless, the presiding physician discovered in him a certain progress of intelligence, which gave him great hopes. In the fifth month, having shown a marked interest in the other sick patients, coupled with a disposition to be careful and attentive, they made him a nurse, or rather a sub-nurse under the special orders of a responsible nurse. I really believe it was done at first to avoid the alternative of sending him adrift, or transferring him to the insane ward of the hospital. In this congenial pursuit he showed such watchfulness and skill, that by and by they found they had got a treasure. Two months after that he began to talk about medicine, and astonished them still more. He became the puzzle of the establishment. The doctor and surgeon would converse with him, and try and lead him to his past life; but when it came to that, he used to put his hands to his head with a face of great distress, and it was clear some impassable barrier lay between his growing intelligence and the past events of his life. Indeed, on one occasion, he said to his kind friend the doctor, "The past!--a black wall! a black wall!"

Ten months after his admission he was promoted to be an attendant, with a salary.

He put by every shilling of it; for he said, "A voice from the dark past tells me money is everything in this world."

A discussion was held by the authorities as to whether he should be informed he had money and jewels at the bank or not.

Upon the whole, it was thought advisable to postpone this information, lest he should throw it away; but they told him he had been picked up at sea, and both money and jewels found on him; they were in safe hands, only the person was away for the time. Still, he was not to look upon himself as either friendless or moneyless.

At this communication he showed an almost childish delight, that confirmed the doctor in his opinion he was acting prudently, and for the real benefit of an amiable and afflicted person, not yet to be trusted with money and jewels.

IN his quality of attendant on the sick, Staines sometimes conducted a weak but convalescent patient into the open air; and he was always pleased to do this, for the air of the Cape carries health and vigor on its wings. He had seen its fine recreative properties, and he divined, somehow, that the minds of convalescents ought to be amused, and so he often begged the doctor to let him take a convalescent abroad. Sooner than not, he would draw the patient several miles in a Bath chair. He rather liked this; for he was a Hercules, and had no egotism or false pride where the sick were concerned.

Now, these open-air walks exerted a beneficial influence on his own darkened mind. It is one thing to struggle from idea to idea; it is another when material objects mingle with the retrospect; they seem to supply stepping-stones in the gradual resuscitation of memory and reason.

The ships going out of port were such a steppingstone to him, and a vague consciousness came back to him of having been in a ship.

Unfortunately, along with this reminiscence came a desire to go in one again; and this sowed discontent in his mind, and the more that mind enlarged, the more he began to dislike the hospital and its confinement. The feeling grew, and bade fair to disqualify him for his humble office. The authorities could not fail to hear of this, and they had a little discussion about parting with him; but they hesitated to turn him adrift, and they still doubted the propriety of trusting him with money and jewels.

While matters were in this state a remarkable event occurred. He drew a sick patient down to the quay one morning, and watched the business of the port with the keenest interest. A ship at anchor was unloading, and a great heavy boat was sticking to her side like a black leech. Presently this boat came away, and moved sluggishly towards the shore, rather by help of the tide than of the two men who went through the form of propelling her with two monstrous sweeps, while a third steered her. She contained English goods: agricultural implements, some cases, four horses, and a buxom young woman with a thorough English face. The woman seemed a little excited, and as she neared the landing-place, she called out in jocund tones to a young man on the shore, "It is all right, Dick; they are beauties," and she patted the beasts as people do who are fond of them.

She stepped lightly ashore, and then came the slower work of landing her imports. She bustled about, like a hen over her brood, and wasn't always talking, but put in her word every now and then, never crossly, and always to the point.

Staines listened to her, and examined her with a sort of puzzled look; but she took no notice of him; her whole soul was in the cattle.

They got the things on board well enough; but the horses were frightened at the gangway, and jibbed. Then a man was for driving them, and poked one of them in the quarter; he snorted and reared directly.

"Man alive!" cried the young woman, "that is not the way. They are docile enough, but frightened. Encourage 'em, and let 'em look at it. Give 'em time. More haste less speed, with timorous cattle."

"That is a very pleasant voice," said poor Staines, rather more dictatorially than became the present state of his intellect. He added softly, "a true woman's voice;" then gloomily, "a voice of the past--the dark, dark past."

At this speech intruding itself upon the short sentences of business, there was a roar of laughter, and Phoebe Falcon turned sharply round to look at the speaker. She stared at him; she cried "Oh!" and clasped her hands, and colored all over. "Why, sure," said she, "I can't be mistook. Those eyes--'tis you, doctor, isn't it?"

"Doctor?" said Staines, with a puzzled look. "Yes; I think they called me doctor once. I'm an attendant in the hospital now."

"Dick!" cried Phoebe, in no little agitation. "Come here this minute."

"What, afore I get the horses ashore?"

"Ay, before you do another thing, or say another word. Come here, now." So he came, and she told him to take a good look at the man. "Now," said she, "who is that?"

"Blest if I know," said he.

"What, not know the man who saved your own life! Oh, Dick, what are your eyes worth?"

This discourse brought the few persons within hearing into one band of excited starers.

Dick took a good look, and said, "I'm blest if I don't, though; it is the doctor that cut my throat."

This strange statement drew forth quite a shout of ejaculations.

"Oh, better breathe through a slit than not at all," said Dick. "Saved my life with that cut, he did, didn't he, Pheeb?"

"That he did, Dick. Dear heart, I hardly know whether I am in my senses or not, seeing him a-looking so blank. You try him."

Dick came forward. "Sure you remember me, sir. Dick Dale. You cut my throat, and saved my life."

"Cut your throat! why, that would kill you."

"Not the way you done it. Well, sir, you ain't the man you was, that is clear; but you was a good friend to me, and there's my hand."

"Thank you, Dick," said Staines, and took his hand. "I don't remember you. Perhaps you are one of the past. The past is dead wall to me--a dark dead wall," and he put his hands to his head with a look of distress.

Everybody there now suspected the truth, and some pointed mysteriously to their own heads.

Phoebe whispered an inquiry to the sick person.

He said a little pettishly, "All I know is, he is the kindest attendant in the ward, and very attentive."

"Oh, then, he is in the public hospital."

"Of course he is."

The invalid, with the selfishness of his class, then begged Staines to take him out of all this bustle down to the beach. Staines complied at once, with the utmost meekness, and said, "Good-by, old friends; forgive me for not remembering you. It is my great affliction that the past is gone from me--gone, gone." And he went sadly away, drawing his sick charge like a patient mule.

Phoebe Falcon looked after him, and began to cry.

"Nay, nay, Phoebe," said Dick; "don't ye take on about it."

"I wonder at you," sobbed Phoebe. "Good people, I'm fonder of my brother than he is of himself, it seems; for I can't take it so easy. Well, the world is full of trouble. Let us do what we are here for. But I shall pray for the poor soul every night, that his mind may be given back to him."

So then she bustled, and gave herself to getting the cattle on shore, and the things put on board her wagon.

But when this was done, she said to her brother, "Dick, I did not think anything on earth could take my heart off the cattle and the things we have got from home; but I can't leave this without going to the hospital about our poor dear doctor: and it is late for making a start, any way--and you mustn't forget the newspapers for Reginald--he is so fond of them--and you must contrive to have one sent out regular after this, and I'll go to the hospital."

She went, and saw the head doctor, and told him he had got an attendant there she had known in England in a very different condition, and she had come to see if there was anything she could do for him--for she felt very grateful to him, and grieved to see him so.

The doctor was pleased and surprised, and put several questions.

Then she gave him a clear statement of what he had done for Dick in England.

"Well," said the doctor, "I believe it is the same man; for, now you tell me this--yes, one of the nurses told me he knew more about medicine than she did. His name, if you please."

"His name, sir?"

"Yes, his name. Of course you know his name. Is it Christie?"

"Doctor," said Phoebe, blushing, "I don't know what you will think of me, but I don't know his name. Laws forgive me, I never had the sense to ask it."

A shade of suspicion crossed the doctor's face.

Phoebe saw it, and colored to the temples. "Oh, sir," she cried piteously, "don't go for to think I have told you a lie! why should I? and indeed I am not of that sort, nor Dick neither. Sir, I'll bring him to you, and he will say the same. Well, we were all in terror and confusion, and I met him accidentally in the street. He was only a customer till then, and paid ready money, so that is how I never knew his name, but if I hadn't been the greatest fool in England, I should have asked his wife."

"What! he has a wife?"

"Ay, sir, the loveliest lady you ever clapped eyes on, and he is almost as handsome; has eyes in his head like jewels; 'twas by them I knew him on the quay, and I think he knew my voice again, said as good as he had heard it in past times."

"Did he? Then we have got him," cried the doctor energetically.

"La, Sir."

"Yes; if he knows your voice, you will be able in time to lead his memory back; at least, I think so. Do you live in Cape Town?"

"Dear heart, no. I live at my own farm, a hundred and eighty miles from this."

"What a pity!"

"Why, sir?"

"Well--hum!"

"Oh, if you think I could do the poor doctor good by having him with me, you have only to say the word, and out he goes with Dick and me to-morrow morning. We should have started for home to-night, but for this."

"Are you in earnest, madam?" said the doctor, opening his eyes. "Would you really encumber yourself with a person whose reason is in suspense, and may never return?"

"But that is not his fault, sir. Why, if a dog had saved my brother's life, I'd take it home, and keep it all its days; and this is a man, and a worthy man. Oh, sir, when I saw him brought down so, and his beautiful eyes clouded like, my very bosom yearned over the poor soul; a kind act done in dear old England, who can see the man in trouble here, and not repay it--ay, if it cost one's blood. But indeed he is strong and healthy, and hands are always scarce our way, and the odds are he will earn his meat one way or t'other; and if he doesn't, why, all the better for me; I shall have the pleasure of serving him for nought that once served me for neither money nor reward."

"You are a good woman," said the doctor warmly.

"There's better, and there's worse," said Phoebe quietly, and even a little coldly.

"More of the latter," said the doctor dryly. "Well, Mrs.--?"

"Falcon, sir."

"We shall hand him over to your care: but first--just for form--if you are a married woman, we should like to see Dick here: he is your husband, I presume."

Ploebe laughed merrily. "Dick is my brother; and he can't be spared to come here. Dick! he'd say black was white if I told him to."

"Then let us see your husband about it--just for form."

"My husband is at the farm. I could not venture so far away, and not leave him in charge." If she had said, "I will not bring him into temptation," that would have been nearer the truth. "Let that fly stick on the wall, sir. What I do, my husband will approve."

"I see how it is. You rule the roost."