by

THE morning-room of a large house in Portman Square, London.

A gentleman in the prime of life stood with his elbow on the broad mantel-piece, and made himself agreeable to a young lady, seated a little way off, playing at work.

To the ear he was only conversing, but his eyes dwelt on her with loving admiration all the time. Her posture was favorable to this furtive inspection, for she leaned her fair head over her work with a pretty, modest, demure air, that seemed to say, "I suspect I am being admired: I will not look to see: I might have to check it."

The gentleman's features were ordinary, except his brow--that had power in it--but he had the beauty of color; his sunburned features glowed with health, and his eye was bright. On the whole, rather good-looking when he smiled, but ugly when he frowned; for his frown was a scowl, and betrayed a remarkable power of hating.

Miss Arabella Bruce was a beauty. She had glorious masses of dark red hair, and a dazzling white neck to set it off; large, dove-like eyes, and a blooming oval face, which would have been classical if her lips had been thin and finely chiseled; but here came in her Anglo-Saxon breed, and spared society a Minerva by giving her two full and rosy lips. They made a smallish mouth at rest, but parted ever so wide when they smiled, and ravished the beholder with long, even rows of dazzling white teeth.

Her figure was tall and rather slim, but not at all commanding. There are people whose very bodies express character; and this tall, supple, graceful frame of Bella Bruce breathed womanly subservience; so did her gestures. She would take up or put down her own scissors half timidly, and look around before threading her needle, as if to see whether any soul objected. Her favorite word was "May I?" with a stress on the "May," and she used it where most girls would say "I will," or nothing, and do it.

Mr. Richard Bassett was in love with her, and also conscious that her fifteen thousand pounds would be a fine addition to his present income, which was small, though his distant expectations were great. As he had known her but one month, and she seemed rather amiable than inflammable, he had the prudence to proceed by degrees; and that is why, though his eyes gloated on her, he merely regaled her with the gossip of the day, not worth recording here. But when he had actually taken his hat to go, Bella Bruce put him a question that had been on her mind the whole time, for which reason she had reserved it to the very last moment.

"Is Sir Charles Bassett in town?" said she, mighty carelessly, but bending a little lower over her embroidery.

"Don't know," said Richard Bassett, with such a sudden brevity and asperity that Miss Bruce looked up and opened her lovely eyes. Mr. Richard Bassett replied to this mute inquiry, "We don't speak." Then, after a pause, "He has robbed me of my inheritance."

"Oh, Mr. Bassett!"

"Yes, Miss Bruce, the Bassett and Huntercombe estates were mine by right of birth. My father was the eldest son, and they were entailed on him. But Sir Charles's father persuaded my old, doting grandfather to cut off the entail, and settle the estates on him and his heirs; and so they robbed me of every acre they could. Luckily my little estate of Highmore was settled on my mother and her issue too tight for the villains to undo."

These harsh expressions, applied to his own kin, and the abruptness and heat they were uttered with, surprised and repelled his gentle listener. She shrank a little away from him. He observed it. She replied not to his words, but to her own thought:

"But, after all, it does seem hard." She added, with a little fervor, "But it wasn't poor Sir Charles's doing, after all."

"He is content to reap the benefit," said Richard Bassett, sternly.

Then, finding he was making a sorry impression, he tried to get away from the subject. I say tried, for till a man can double like a hare he will never get away from his hobby. "Excuse me," said he; "I ought never to speak about it. Let us talk of something else. You cannot enter into my feelings; it makes my blood boil. Oh, Miss Bruce! you can't conceive what a disinherited man feels--and I live at the very door: his old trees, that ought to be mine, fling their shadows over my little flower beds; the sixty chimneys of Huntercombe Hall look down on my cottage; his acres of lawn run up to my little garden, and nothing but a ha-ha between us."

"It is hard," said Miss Bruce, composedly; not that she entered into a hardship of this vulgar sort, but it was her nature to soothe and please people.

"Hard!" cried Richard Bassett, encouraged by even this faint sympathy; "it would be unendurable but for one thing--I shall have my own some day."

"I am glad of that," said the lady; "but how?"

"By outliving the wrongful heir."

Miss Bruce turned pale. She had little experience of men's passions. "Oh, Mr. Bassett!" said she--and there was something pure and holy in the look of sorrow and alarm she cast on the presumptuous speaker--"pray do not cherish such thoughts. They will do you harm. And remember life and death are not in our hands. Besides--"

"Well?"'

"Sir Charles might--"

"Well?"

"Might he not--marry--and have children?" This with more hesitation and a deeper blush than appeared absolutely necessary.

"Oh, there's no fear of that. Property ill-gotten never descends. Charles is a worn-out rake. He was fast at Eton--fast at Oxford--fast in London. Why, he looks ten years older than I, and he is three years younger. He had a fit two years ago. Besides, he is not a marrying man. Bassett and Huntercombe will be mine. And oh! Miss Bruce, if ever they are mine--"

"Sir Charles Bassett!" trumpeted a servant at the door; and then waited, prudently, to know whether his young lady, whom he had caught blushing so red with one gentleman, would be at home to another.

"Wait a moment," said Miss Bruce to him. Then, discreetly ignoring what Bassett had said last, and lowering her voice almost to a whisper, she said, hurriedly: "You should not blame him for the faults of others. There--I have not been long acquainted with either, and am little entitled to inter-- But it is such a pity you are not friends. He is very good, I assure you, and very nice. Let me reconcile you two. May I?"

This well-meant petition was uttered very sweetly; and, indeed--if I may be permitted--in a way to dissolve a bear.

But this was not a bear, nor anything else that is placable; it was a man with a hobby grievance; so he replied in character:

"That is impossible so long as he keeps me out of my own." He had the grace, however, to add, half sullenly, "Excuse me; I feel I have been too vehement."

Miss Bruce, thus repelled, answered, rather coldly:

"Oh, never mind that; it was very natural.--I am at home, then," said she to the servant.

Mr. Bassett took the hint, but turned at the door, and said, with no little agitation, "I was not aware he visits you. One word--don't let his ill-gotten acres make you quite forget the disinherited one." And so he left her, with an imploring look.

She felt red with all this, so she slipped out at another door, to cool her cheeks and imprison a stray curl for Sir Charles.

He strolled into the empty room, with the easy, languid air of fashion. His features were well cut, and had some nobility; but his sickly complexion and the lines under his eyes told a tale of dissipation. He appeared ten years older than he was, and thoroughly blasé.

Yet when Miss Bruce entered the room with a smile and a little blush, he brightened up and looked handsome, and greeted her with momentary warmth.

After the usual inquiries she asked him if he had met any body.

"Where?"

"Here; just now."

"No."

"What, nobody at all?"

"Only my sulky cousin; I don't call him anybody," drawled Sir Charles, who was now relapsing into his normal condition of semi-apathy.

"Oh," said Miss Bruce gayly, "you must expect him to be a little cross. It is not so very nice to be disinherited, let me tell you."

"And who has disinherited the fellow?"

"I forget; but you disinherited him among you. Never mind; it can't be helped now. When did you come back to town? I didn't see you at Lady d'Arcy's ball, did I?"

"You did not, unfortunately for me; but you would if I had known you were to be there. But about Richard: he may tell you what he likes, but he was not disinherited; he was bought out. The fact is, his father was uncommonly fast. My grandfather paid his debts again and again; but at last the old gentleman found he was dealing with the Jews for his reversion. Then there was an awful row. It ended in my grandfather outbidding the Jews. He bought the reversion of his estate from his own son for a large sum of money (he had to raise it by mortgages); then they cut off the entail between them, and he entailed the mortgaged estate on his other son, and his grandson (that was me), and on my heir-at-law. Richard's father squandered his thirty thousand pounds before he died; my father husbanded the estates, got into Parliament, and they put a tail to his name."

Sir Charles delivered this version of the facts with a languid composure that contrasted deliciously with Richard's heat in telling the story his way (to be sure, Sir Charles had got Huntercombe and Bassett, and it is easier to be philosophical on the right side of the boundary hedge), and wound up with a sort of corollary: "Dick Bassett suffers by his father's vices, and I profit by mine's virtues. Where's the injustice?"

"Nowhere, and the sooner you are reconciled the better."

Sir Charles demurred. "Oh, I don't want to quarrel with the fellow: but he is a regular thorn in my side, with his little trumpery estate, all in broken patches. He shoots my pheasants in the unfairest way." Here the landed proprietor showed real irritation, but only for a moment. He concluded calmly, "The fact is, he is not quite a gentleman. Fancy his coming and whining to you about our family affairs, and then telling you a falsehood!"

"No, no; be did not mean. It was his way of looking at things. You can afford to forgive him."

"Yes, but not if he sets you against me."

"But he cannot do that. The more any one was to speak against you, the more I--of course."

This admission fired Sir Charles; he drew nearer, and, thanks to his cousin's interference, spoke the language of love more warmly and directly than he had ever done before.

The lady blushed, and defended herself feebly. Sir Charles grew warmer, and at last elicited from her a timid but tender avowal, that made him supremely happy.

When he left her this brief ecstasy was succeeded by regrets on account of the years he had wasted in follies and intrigues.

He smoked five cigars, and pondered the difference between the pure creature who now honored him with her virgin affections and beauties of a different character who had played their parts in his luxurious life.

After profound deliberation he sent for his solicitor. They lighted the inevitable cigars, and the following observations struggled feebly out along with the smoke.

"Mr. Oldfield, I'm going to be married."

"Glad to hear it, Sir Charles." (Vision of settlements.) "It is a high time you were." (Puff-puff.)

"Want your advice and assistance first."

"Certainly."

"Must put down my pony-carriage now, you know."

"A very proper retrenchment; but you can do that without my assistance,

"There would be sure to be a row if I did. I dare say there will be as it is. At any rate, I want to do the thing like a gentleman."

"Send 'em to Tattersall's." (Puff.)

"And the girl that drives them in the park, and draws all the duchesses and countesses at her tail--am I to send her to Tattersall's?" (Puff.)

"Oh, it is her you want to put down, then?"

"Why, of course."

SIR CHARLES and Mr. Oldfield settled that lady's retiring pension, and Mr. Oldfield took the memoranda home, with instructions to prepare a draft deed for Miss Somerset's approval.

Meantime Sir Charles visited Miss Bruce every day. Her affections for him grew visibly, for being engaged gave her the courage to love.

Mr. Bassett called pretty often; but one day he met Sir Charles on the stairs, and scowled.

That scowl cost him dear, for Sir Charles thereupon represented to Bella that a man with a grievance is a bore to the very eye, and asked her to receive no more visits from his scowling cousin. The lady smiled, and said, with soft complacency, "I obey."

Sir Charles's gallantry was shocked.

"No, don't say 'obey.' It is a little favor I ventured to ask."

"It is like you to ask what you have a right to command. I shall be out to him in future, and to every one who is disagreeable to you. What! does 'obey' frighten you from my lips? To me it is the sweetest in the language. Oh, please let me 'obey' you! May I?"

Upon this, as vanity is seldom out of call, Sir Charles swelled like a turkey-cock, and loftily consented to indulge Bella Bruce's strange propensity. From that hour she was never at home to Mr. Bassett.

He began to suspect; and one day, after he had been kept out with the loud, stolid "Not at home" of practiced mendacity, he watched, and saw Sir Charles admitted.

He divined it all in a moment, and turned to wormwood. What! was he to be robbed of the lady he loved--and her fifteen thousand pounds--by the very man who had robbed him of his ancestral fields? He dwelt on the double grievance till it nearly frenzied him. But he could do nothing: it was his fate. His only hope was that Sir Charles, the arrant flirt, would desert this beauty after a time, as he had the others.

But one afternoon, in the smoking-room of his club, a gentleman said to him, "So your cousin Charles is engaged to the Yorkshire beauty, Bell Bruce?"

"He is flirting with her, I believe," said Richard.

"No, no," said the other; "they are engaged. I know it for a fact. They are to be married next month."

Mr. Richard Bassett digested this fresh pill in moody silence, while the gentlemen of the club discussed the engagement with easy levity. They soon passed to a topic of wider interest, viz., who was to succeed Sir Charles with La Somerset. Bassett began to listen attentively, and learned for the first time Sir Charles Bassett's connection with that lady, and also that she was a woman of a daring nature and furious temper. At first he was merely surprised; but soon hatred and jealousy whispered in his ear that with these materials it must be possible to wound those who had wounded him.

Mr. Marsh, a young gentleman with a receding chin, and a mustache between hay and straw, had taken great care to let them all know he was acquainted with Miss Somerset. So Richard got Marsh alone, and sounded him. Could he call upon the lady without ceremony?

"You won't get in. Her street door is jolly well guarded, I can tell you."

"I am very curious to see her in her own house."

"So are a good many fellows."

"Could you not give me an introduction?"

Marsh shook his head sapiently for a considerable time, and with all this shaking, as it appeared, out fell words of wisdom. "Don't see it. I'm awfully spooney on her myself; and, you know, when a fellow introduces another fellow, that fellow always cuts the other out." Then, descending from the words of the wise and their dark sayings to a petty but pertinent fact, he added, "Besides, I'm only let in myself about once in five times."

"She gives herself wonderful airs, it seems," said Bassett, rather bitterly.

Marsh fired up. "So would any woman that was as beautiful, and as witty and as much run after as she is. Why she is a leader of fashion. Look at all the ladies following her round the park. They used to drive on the north side of the Serpentine. She just held up her finger, and now they have cut the Serpentine, and followed her to the south drive."

"Oh, indeed!" said Bassett. "Ah then this is a great lady; a poor country squire must not venture into her august presence." He turned savagely on his heel, and Marsh went and made sickly mirth at his expense.

By this means the matter soon came to the ears of old Mr. Woodgate, the father of that club, and a genial gossip. He got hold of Bassett in the dinner-room and examined him. "So you want an introduction to La Somerset, and Marsh refuses--Marsh, hitherto celebrated for his weak head rather than his hard heart?"

Richard Bassett nodded rather sullenly. He had not bargained for this rapid publicity.

The venerable chief resumed: "We all consider Marsh's conduct unclubable and a thing to be combined against. Wanted--an Anti-dog-in-the-manger League. I'll introduce you to the Somerset."

"What! do you visit her?" asked Bassett, in some astonishment.

The old gentleman held up his hands in droll disclaimer, and chuckled merrily "No, no; I enjoy from the shore the disasters of my youthful friends--that sacred pleasure is left me. Do you see that elegant creature with the little auburn beard and mustache, waiting sweetly for his dinner. He launched the Somerset."

"Launched her?"

"Yes; but for him she might have wasted her time breaking hearts and slapping faces in some country village. He it was set her devastating society; and with his aid she shall devastate you.--Vandeleur, will you join Bassett and me?"

Mr. Vandeleur, with ready grace, said he should be delighted, and they dined together accordingly.

Mr. Vandeleur, six feet high, lank, but graceful as a panther, and the pink of politeness, was, beneath his varnish, one of the wildest young men in London--gambler, horse-racer, libertine, what not?--but in society charming, and his manners singularly elegant and winning. He never obtruded his vices in good company; in fact, you might dine with him all your life and not detect him. The young serpent was torpid in wine; but he came out, a bit at a time, in the sunshine of Cigar.

After a brisk conversation on current topics, the venerable chief told him plainly they were both curious to know the history of Miss Somerset, and he must tell it them.

"Oh, with pleasure," said the obliging youth. "Let us go into the smoking-room."

"Let--me--see. I picked her up by the sea-side. She promised well at first. We put her on my chestnut mare, and she showed lots of courage, so she soon learned to ride; but she kicked, even down there."

"Kicked!--whom?"

"Kicked all round; I mean showed temper. And when she got to London, and had ridden a few times in the park, and swallowed flattery, there was no holding her. I stood her cheek for a good while, but at last I told the servants they must not turn her out, but they could keep her out. They sided with me for once. She had ridden over them, as well. The first time she went out they bolted the doors, and handed her boxes up the area steps."

"How did she take that?"

"Easier than we expected. She said, 'Lucky for you beggars that I'm a lady, or I'd break every d--d window in the house.'"

This caused a laugh. It subsided. The historian resumed.

"Next day she cooled, and wrote a letter."

"To you?"

"No, to my groom. Would you like to see it? It is a curiosity."

He sent one of the club waiters for his servant, and his servant for his desk, and produced the letter.

"There!" said Vandeleur. "She looks like a queen, and steps like an empress, and this is how she writes:

"DEAR JORGE-- i have got the sak, an' praps your turn nex. dear jorge he alwaies promise me the grey oss, which now an oss is life an death to me. If you was to ast him to lend me the grey he wouldn't refuse you,

"Yours respecfully,

"RHODA SOMERSET."

When the letter and the handwriting, which, unfortunately, I cannot reproduce, had been duly studied and approved, Vandeleur continued--

"Now, you know, she had her good points, after all. If any creature was ill, she'd sit up all night and nurse them, and she used to go to church on Sundays, and come back with the sting out of her; only then she would preach to a fellow, and bore him. She is awfully fond of preaching. Her dream is to jump on a first-rate hunter, and ride across country, and preach to the villages. So, when George came grinning to me with the letter, I told him to buy a new side-saddle for the gray, and take her the lot, with my compliments. I had noticed a slight spavin in his near foreleg. She rode him that very day in the park, all alone, and made such a sensation that next day my gray was standing in Lord Hailey's stables. But she rode Hailey, like my gray, with a long spur, and he couldn't stand it. None of 'em could except Sir Charles Bassett, and he doesn't play fair--never goes near her."

"And that gives him an unfair advantage over his fascinating predecessors?" inquired the senior, slyly.

"Of course it does," said Vandeleur, stoutly. "You ask a girl to dine at Richmond once a month, and keep out of her way all the rest of the time, and give her lots of money--she will never quarrel with you."

"Profit by this information, young man," said old Woodgate, severely; "it comes too late for me. In my day there existed no sure method of pleasing the fair. But now that is invented, along with everything else. Richmond and--absence, equivalent to 'Richmond and victory!' Now, Bassett, we have heard the truth from the fountain-head, and it is rather serious. She swears, she kicks, she preaches. Do you still desire an introduction? As for me, my manly spirit is beginning to quake at Vandeleur's revelations, and some lines of Scott recur to my Gothic memory--

"'From the chafed tiger rend his prey,

Bar the fell dragon's blighting way,

But shun that lovely snare."'

Bassett replied, gravely, that he had no such motive as Mr. Woodgate gave him credit for, but still desired the introduction.

"With pleasure," said Vandeleur; "but it will be no use to you. She hates me like poison; says I have no heart. That is what all ill-tempered women say."

Notwithstanding his misgivings the obliging youth called for writing materials, and produced the following epistle--

"DEAR MISS SOMERSET--Mr. Richard Bassett, a cousin of Sir Charles, wishes very much to be introduced to you, and has begged me to assist in an object so laudable. I should hardly venture to present myself, and, therefore, shall feel surprised as well as flattered if you will receive Mr. Bassett on my introduction, and my assurance that he is a respectable country gentleman, and bears no resemblance in character to

"Yours faithfully,

"ARTHUR VANDELEUR."

Next day Bassett called at Miss Somerset's house in May Fair, and delivered his introduction.

He was admitted after a short delay and entered the lady's boudoir. It was Luxury's nest. The walls were rose colored satin, padded and puckered; the voluminous curtains were pale satin, with floods and billows of real lace; the chairs embroidered, the tables all buhl and ormolu, and the sofas felt like little seas. The lady herself, in a delightful peignoir, sat nestled cozily in a sort of ottoman with arms. Her finely formed hand, clogged with brilliants, was just conveying brandy and soda-water to a very handsome mouth when Richard Bassett entered.

She raised herself superbly, but without leaving her seat, and just looked at a chair in a way that seemed to say, "I permit you to sit down;" and that done, she carried the glass to her lips with the same admirable firmness of hand she showed in driving. Her lofty manner, coupled with her beautiful but rather haughty features, smacked of imperial origin. Yet she was the writer to "jorge," and four years ago a shrimp-girl, running into the sea with legs as brown as a berry.

So swiftly does merit rise in this world which, nevertheless, some morose folk pretend is a wicked one.

I ought to explain, however, that this haughty reception was partly caused by a breach of propriety. Vandeleur ought first to have written to her and asked permission to present Richard Bassett. He had no business to send the man and the introduction together. This law a Parliament of Sirens had passed, and the slightest breach of it was a bitter offense Equilibrium governs the world. These ladies were bound to be overstrict in something or other, being just a little lax in certain things where other ladies are strict.

Now Bassett had pondered well what he should say, but he was disconcerted by her superb presence and demeanor and her large gray eyes, that rested steadily upon his face.

However, he began to murmur mellifluously. Said he had often seen her in public, and admired her, and desired to make her acquaintance, etc., etc.

"Then why did you not ask Sir Charles to bring you here?" said Miss Somerset, abruptly, and searching him with her eyes, that were not to say bold, but singularly brave, and examiners pointblank.

"I am not on good terms with Sir Charles. He holds the estates that ought to be mine; and now he has robbed me of my love. He is the last man in the world I would ask a favor of."

"You came here to abuse him behind his back, eh?" asked the lady with undisguised contempt.

Bassett winced, but kept his temper. "No, Miss Somerset; but you seem to think I ought to have come to you through Sir Charles. I would not enter your house if I did not feel sure I shall not meet him here."

Miss Somerset looked rather puzzled. "Sir Charles does not come here every day, but he comes now and then, and he is always welcome."

"You surprise me."

"Thank you. Now some of my gentlemen friends think it is a wonder he does not come every minute."

"You mistake me. What surprises me is that you are such good friends under the circumstances."

"Circumstances! what circumstances?"

"Oh, you know. You are in his confidence, I presume?"--this rather satirically. So the lady answered, defiantly:

"Yes, I am; he knows I can hold my tongue, so he tells me things he tells nobody else."

"Then, if you are in his confidence, you know he is about to be married."

"Married! Sir Charles married!"

"In three weeks."

"It's a lie! You get out of my house this moment!"

Mr. Bassett colored at this insult. He rose from his seat with some little dignity, made her a low bow, and retired. But her blood was up: she made a wonderful rush, sweeping down a chair with her dress as she went, and caught him at the door, clutched him by the shoulder and half dragged him back, and made him sit down again, while she stood opposite him, with the knuckles of one hand resting on the table.

"Now," said she, panting, "you look me in the face and say that again."

"Excuse me; you punish me too severely for telling the truth."

"Well, I beg your pardon--there. Now tell me--this instant. Can't you speak, man?" And her knuckles drummed the table.

"He is to be married in three weeks."

"Oh! Who to?"

"A young lady I love."

"Her name?"

"Miss Arabella Bruce."

"Where does she live?"

"Portman Square."

"I'll stop that marriage."

"How?" asked Richard, eagerly.

"I don't know; that I'll think over. But he shall not marry her--never!"

Bassett sat and looked up with almost as much awe as complacency at the fury he had evoked; for this woman was really at times a poetic impersonation of that fiery passion she was so apt to indulge. She stood before him, her cheek pale, her eyes glittering and roving savagely, and her nostrils literally expanding, while her tall body quivered with wrath, and her clinched knuckles pattered on the table.

"He shall not marry her. I'll kill him first!"

RICHARD BASSETT eagerly offered his services to break off the obnoxious match. But Miss Somerset was beginning to be mortified at having shown so much passion before a stranger.

"What have you to do with it?" said she, sharply.

"Everything. I love Miss Bruce."

"Oh, yes; I forgot that. Anything else? There is, now. I see it in your eye. What is it?"

"Sir Charles's estates are mine by right, and they will return to my line if he does not marry and have issue."

"Oh, I see. That is so like a man. It's always love, and something more important, with you. Well, give me your address. I'll write if I want you."

"Highly flattered," said Bassett, ironically-wrote his address and left her.

Miss Somerset then sat down and wrote:

"DEAR SIR CHARLES--please call here, I want to speak to you.

yours respecfuly,

"RHODA SOMERSET."

Sir Charles obeyed this missive, and the lady received him with a gracious and smiling manner, all put on and catlike. She talked with him of indifferent things for more than an hour, still watching to see if he would tell her of his own accord.

When she was quite sure he would not, she said,

"Do you know there's a ridiculous report about that you are going to be married?"

"Indeed!"

"They even tell her name--Miss Bruce. Do you know the girl?"

"Yes."

"Is she pretty?"

"Very."

"Modest?"

"As an angel."

"And are you going to marry her?"

"Yes."

"Then you are a villain."

"The deuce I am!"

"You are, to abandon a woman who has sacrificed all for you."

Sir Charles looked puzzled, and then smiled; but was too polite to give his thoughts vent. Nor was it necessary; Miss Somerset, whose brave eyes never left the person she was speaking to, fired up at the smile alone, and she burst into a torrent of remonstrance, not to say vituperation. Sir Charles endeavored once or twice to stop it, but it was not to be stopped; so at last he quietly took up his hat, to go.

He was arrested at the door by a rustle and a fall. He turned round, and there was Miss Somerset lying on her back, grinding her white teeth and clutching the air.

He ran to the bell and rang it violently, then knelt down and did his best to keep her from hurting herself; but, as generally happens in these cases, his interference made her more violent. He had hard work to keep her from battering her head against the floor, and her arms worked like windmills.

Hearing the bell tugged so violently, a pretty page ran headlong into the room--saw--and; without an instant's diminution of speed, described a curve, and ran headlong out, screaming "Polly! Polly!"

The next moment the housekeeper, an elderly woman, trotted in at the door, saw her mistress's condition, and stood stock-still, calling, "Polly," but with the most perfect tranquillity the mind can conceive.

In ran a strapping house-maid, with black eyes and brown arms, went down on her knees, and said, firmly though respectfully, "Give her me, sir."

She got behind her struggling mistress, pulled her up into her own lap, and pinned her by the wrists with a vigorous grasp.

The lady struggled, and ground her teeth audibly, and flung her arms abroad. The maid applied all her rustic strength and harder muscle to hold her within bounds. The four arms went to and fro in a magnificent struggle, and neither could the maid hold the mistress still, nor the mistress shake off the maid's grasp, nor strike anything to hurt herself.

Sir Charles, thrust out of the play looked on with pity and anxiety, and the little page at the door--combining art and nature--stuck stock-still in a military attitude, and blubbered aloud.

As for the housekeeper, she remained in the middle of the room with folded arms, and looked down on the struggle with a singular expression of countenance. There was no agitation whatever, but a sort of thoughtful examination, half cynical, half admiring.

However, as soon as the boy's sobs reached her ear she wakened up, and said, tenderly, "What is the child crying for? Run and get a basin of water, and fling it all over her; that will bring her to in a minute."

The page departed swiftly on this benevolent errand.

Then the lady gave a deep sigh, and ceased to struggle.

Next she stared in all their faces, and seemed to return to consciousness.

Next she spoke, but very feebly. "Help me up," she sighed.

Sir Charles and Polly raised her, and now there was a marvelous change. The vigorous vixen was utterly weak, and limp as a wet towel--a woman of jelly. As such they handled her, and deposited her gingerly on the sofa.

Now the page ran in hastily with the water. Up jumps the poor lax sufferer, with flashing eyes: "You dare come near me with it!" Then to the female servants: "Call yourselves women, and water my lilac silk, not two hours old?" Then to the housekeeper: "You old monster, you wanted it for your Polly. Get out of my sight, the lot!"

Then, suddenly remembering how feeble she was, she sank instantly down, and turned piteously and languidly to Sir Charles. "They eat my bread, and rob me, and hate me," said she, faintly. "I have but one friend on earth." She leaned tenderly toward Sir Charles as that friend; but before she quite reached him she started back, her eyes filled with sudden horror. "And he forsakes me!" she cried; and so turned away from him despairingly, and began to cry bitterly, with head averted over the sofa, and one hand hanging by her side for Sir Charles to take and comfort her. He tried to take it. It resisted; and, under cover of that little disturbance, the other hand dexterously whipped two pins out of her hair. The long brown tresses--all her own--fell over her eyes and down to her waist, and the picture of distressed beauty was complete.

Even so did the women of antiquity conquer male pity--"solutis crinibus."

The females interchanged a meaning glance, and retired; then the boy followed them with his basin, sore perplexed, but learning life in this admirable school.

Sir Charles then, with the utmost kindness, endeavored to reconcile the weeping and disheveled fair to that separation which circumstances rendered necessary. But she was inconsolable, and he left the house, perplexed and grieved; not but what it gratified his vanity a little to find himself beloved all in a moment, and the Somerset unvixened. He could not help thinking how wide must be the circle of his charms, which had won the affections of two beautiful women so opposite in character as Bella Bruce and La Somerset.

The passion of this latter seemed to grow. She wrote to him every day, and begged him to call on her.

She called on him--she who had never called on a man before.

She raged with jealousy; she melted with grief. She played on him with all a woman's artillery; and at last actually wrung from him what she called a reprieve.

Richard Bassett called on her, but she would not receive him; so then he wrote to her, urging co-operation, and she replied, frankly, that she took no interest in his affairs; but that she was devoted to Sir Charles, and should keep him for herself. Vanity tempted her to add that he (Sir Charles) was with her every day, and the wedding postponed.

This last seemed too good to be true, so Richard Bassett set his servant to talk to the servants in Portman Square. He learned that the wedding was now to be on the 15th of June, instead of the 31st of May.

Convinced that this postponement was only a blind, and that the marriage would never be, he breathed more freely at the news.

But the fact is, although Sir Charles had yielded so far to dread of scandal, he was ashamed of himself, and his shame became remorse when he detected a furtive tear in the dove-like eyes of her he really loved and esteemed.

He went and told his trouble to Mr. Oldfield. "I am afraid she will do something desperate," he said.

Mr. Oldfield heard him out, and then asked him had he told Miss Somerset what he was going to settle on her.

"Not I. She is not in a condition to be influenced by that, at present."

"Let me try her. The draft is ready. I'll call on her to-morrow." He did call, and was told she did not know him.

"You tell her I am a lawyer, and it is very much to her interest to see me," said Mr. Oldfield to the page.

He was admitted, but not to a tête-a-tête. Polly was kept in the room. The Somerset had peeped, and Oldfield was an old fellow, with white hair; if he had been a young fellow, with black hair, she might have thought that precaution less necessary.

"First, madam," said Oldfield, "I must beg you to accept my apologies for not coming sooner. Press of business, etc."

"Why have you come at all? That is the question," inquired the lady, bluntly.

"I bring the draft of a deed for your approval. Shall I read it to you?"

"Yes; if it is not very long." He began to read it. The lady interrupted him characteristically.

"It's a beastly rigmarole. What does it mean--in three words?"

"Sir Charles Bassett secures to Rhoda Somerset four hundred pounds a year, while single; this is reduced to two hundred if you marry. The deed further assigns to you, without reserve, the beneficial lease of this house, and all the furniture and effects, plate, linen, wine, etc."

"I see--a bribe."

"Nothing of the kind, madam. When Sir Charles instructed me to prepare this deed he expected no opposition on your part to his marriage; but he thought it due to him and to yourself to mark his esteem for you, and his recollection of the pleasant hours he has spent in your company."

Miss Somerset's eyes searched the lawyer's face. He stood the battery unflinchingly. She altered her tone, and asked, politely and almost respectfully, whether she might see that paper.

Mr. Oldfield gave it her. She took it, and ran her eye over it; in doing which, she raised it so that she could think behind it unobserved. She handed it back at last, with the remark that Sir Charles was a gentleman and had done the right thing.

"He has; and you will do the right thing too, will you not?"

"I don't know. I am just beginning to fall in love with him myself."

"Jealousy, madam, not love," said the old lawyer. "Come, now! I see you are a young lady of rare good sense; look the thing in the face: Sir Charles is a landed gentleman; he must marry, and, have heirs. He is over thirty, and his time has come. He has shown himself your friend; why not be his? He has given you the means to marry a gentleman of moderate income, or to marry beneath you, if you prefer it--"

"And most of us do--"

"Then why not make his path smooth? Why distress him with your tears and remonstrances?"

He continued in this strain for some time, appealing to her good sense and her better feelings.

When he had done she said, very quietly, "How about the ponies and my brown mare? Are they down in the deed?"

"I think not; but if you will do your part handsomely I'll guarantee you shall have them."

"You are a good soul." Then, after a pause, "Now just you tell me exactly what you want me to do for all this."

Oldfield was pleased with this question. He said, "I wish you to abstain from writing to Sir Charles, and him to visit you only once more before his marriage, just to shake hands and part, with mutual friendship and good wishes."

"You are right," said she, softly; "best for us both, and only fair to the girl." Then, with sudden and eager curiosity, "Is she very pretty?"

"I don't know."

"What, hasn't he told you?"

"He says she is lovely, and every way adorable; but then he is in love. The chances are she is not half so handsome as yourself."

"And yet he is in love with her?"

"Over head and ears."

"I don't believe it. If he was really in love with one woman he couldn't be just to another. I couldn't. He'll be coming back to me in a few months."

"God forbid!"

"Thank you, old gentleman."

Mr. Oldfield began to stammer excuses. She interrupted him: "Oh, bother all that; I like you none the worse for speaking your mind." Then, after a pause, "Now excuse me; but suppose Sir Charles should change his mind, and never sign this paper?"

"I pledge my professional credit."

"That is enough, sir; I see I can trust you. Well, then, I consent to break off with Sir Charles, and only see him once more--as a friend. Poor Sir Charles! I hope he will be happy" (she squeezed out a tear for him)--"happier than I am. And when he does come he can sign the deed, you know."

Mr. Oldfield left her, and joined Sir Charles at Long's, as had been previously agreed.

"It is all right, Sir Charles; she is a sensible girl, and will give you no further trouble."

"How did you get over the hysterics?"

"We dispensed with them. She saw at once it was to be business, not sentiment. You are to pay her one more visit, to sign, and part friends. If you please, I'll make that appointment with both parties, as soon as the deed is engrossed. Oh, by-the-by, she did shed a tear or two, but she dried them to ask me for the ponies and the brown mare."

Sir Charles's vanity was mortified. But he laughed it off, and said she should have them, of course.

So now his mind was at ease, his conscience was at rest, and he could give his whole time where he had given his heart.

Richard Bassett learned, through his servant, that the wedding-dresses were ordered. He called on Miss Somerset. She was out.

Polly opened the door and gave him a look of admiration--due to his fresh color--that encouraged him to try and enlist her in his service.

He questioned her, and she told him in a general way how matters were going. "But," said she, "why not come and talk to her yourself? Ten to one but she tells you. She is pretty outspoken."

"My pretty dear," said Richard, "she never will receive me."

"Oh, but I'll make her!" said Polly.

And she did exert her influence as follows:

"Lookee here, the cousin's a-coming to-morrow and I've been and promised he should see you."

"What did you do that for?"

"Why, he's a well-looking chap, and a beautiful color, fresh from the country, like me. And he's a gentleman, and got an estate belike; and why not put yourn to hisn, and so marry him and be a lady? You might have me about ye all the same, till my turn comes."

"No, no," said Rhoda; "that's not the man for me. If ever I marry, it must be one of my own sort, or else a fool, like Marsh, that I can make a slave of."

"Well, any way, you must see him, not to make a fool of me, for I did promise him; which, now I think on't, 'twas very good of me, for I could find in my heart to ask him down into the kitchen, instead of bringing him upstairs to you."

All this ended, somehow, in Mr. Bassett's being admitted.

To his anxious inquiry how matters stood, she replied coolly that Sir Charles and herself were parted by mutual consent.

"What! after all your protestations?" said Bassett, bitterly.

But Miss Somerset was not in an irascible humor just then. She shrugged her shoulders, and said:

"Yes, I remember I put myself in a passion, and said some ridiculous things. But one can't be always a fool. I have come to my senses. This sort of thing always does end, you know. Most of them part enemies, but he and I part friends and well-wishers."

"And you throw me over as if I was nobody," said Richard, white with anger.

"Why, what are you to me?" said the Somerset. "Oh, I see. You thought to make a cat's-paw of me. Well, you won't, then."

"In other words, you have been bought off."

"No, I have not. I am not to be bought by anybody--and I am not to be insulted by you, you ruffian! How dare you come here and affront a lady in her own house--a lady whose shoestrings your betters are ready to tie, you brute? If you want to be a landed proprietor, go and marry some ugly old hag that's got it, and no eyesight left to see you're no gentleman. Sir Charles's land you'll never have; a better man has got it, and means to keep it for him and his. Here, Polly! Polly! Polly! take this man down to the kitchen, and teach him manners if you can: he is not fit for my drawing-room, by a long chalk."

Polly arrived in time to see the flashing eyes, the swelling veins, and to hear the fair orator's peroration.

"What, you are in your tantrums again!" said she. "Come along, sir. Needs must when the devil drives. You'll break a blood-vessel some day, my lady, like your father afore ye."

And with this homely suggestion, which always sobered Miss Somerset, and, indeed, frightened her out of her wits, she withdrew the offender. She did not take him into the kitchen, but into the dining-room, and there he had a long talk with her, and gave her a sovereign.

She promised to inform him if anything important should occur.

He went away, pondering and scowling deeply.

SIR CHARLES BASSETT was now living in Elysium. Never was rake more thoroughly transformed. Every day he sat for hours at the feet of Bella Bruce, admiring her soft, feminine ways and virgin modesty even more than her beauty. And her visible blush whenever he appeared suddenly, and the soft commotion and yielding in her lovely frame whenever he drew near, betrayed his magnetic influence, and told all but the blind she adored him.

She would decline all invitations to dine with him and her father--a strong-minded old admiral, whose authority was unbounded, only, to Bella's regret, very rarely exerted. Nothing would have pleased her more than to be forbidden this and commanded that; but no! the admiral was a lion with an enormous paw, only he could not be got to put it into every pie.

In this charming society the hours glided, and the wedding-day drew close. So deeply and sincerely was Sir Charles in love that when Mr. Oldfield's letter came, appointing the day and hour to sign Miss Somerset's deed, he was unwilling to go, and wrote back to ask if the deed could not be sent to his house.

Mr. Oldfield replied that the parties to the deed and the witnesses must meet, and it would be unadvisable, for several reasons, to irritate the lady's susceptibility previous to signature; the appointment having been made at her house, it had better remain so.

That day soon came.

Sir Charles, being due in Mayfair at 2 P.M., compensated himself for the less agreeable business to come by going earlier than usual to Portman Square. By this means he caught Miss Bruce and two other young ladies inspecting bridal dresses. Bella blushed and looked ashamed, and, to the surprise of her friends, sent the dresses away, and set herself to talk rationally with Sir Charles--as rationally as lovers can.

The ladies took the cue, and retired in disgust.

Sir Charles apologized.

"This is too bad of me. I come at an unheard-of hour, and frighten away your fair friends; but the fact is, I have an appointment at two, and I don't know how long they will keep me, so I thought I would make sure of two happy hours at the least."

And delightful hours they were. Bella Bruce, excited by this little surprise, leaned softly on his shoulder, and prattled her maiden love like some warbling fountain.

Sir Charles, transfigured by love, answered her in kind--three months ago he could not--and they compared pretty little plans of wedded life, and had small differences, and ended by agreeing.

Complete and prompt accord upon two points: first, they would not have a single quarrel, like other people; their love should never lose its delicate bloom; second, they would grow old together, and die the same day--the same minute if possible; if not, they must be content with the same day, but, on that, inexorable.

But soon after this came a skirmish. Each wanted to obey t'other.

Sir Charles argued that Bella was better than he, and therefore more fit to conduct the pair.

Bella, who thought him divinely good, pounced on this reason furiously. He defended it. He admitted, with exemplary candor, that he was good now--"awfully good." But he assured her that he had been anything but good until he knew her; now she had been always good; therefore, he argued, as his goodness came originally from her, for her to obey him would be a little too much like the moon commanding the sun.

"That is too ingenious for me, Charles," said Bella. "And, for shame! Nobody was ever so good as you are. I look up to you and-- Now I could stop your mouth in a minute. I have only to remind you that I shall swear at the altar to obey you, and you will not swear to obey me. But I will not crush you under the Prayer-book--no, dearest; but, indeed, to obey is a want of my nature, and I marry you to supply that want: and that's a story, for I marry you because I love and honor and worship and adore you to distraction, my own--own--own!" With this she flung herself passionately, yet modestly on his shoulder, and, being there, murmured, coaxingly, "You will let me obey you, Charles?"

Thereupon Sir Charles felt highly gelatinous, and lost, for the moment, all power of resistance or argument.

"Ah, you will; and then you will remind me of my dear mother. She knew how to command; but as for poor dear papa, he is very disappointing. In selecting an admiral for my parent, I made sure of being ordered about. Instead of that--now I'll show you--there he is in the next room, inventing a new system of signals, poor dear--"

She threw the folding-doors open.

"Papa dear, shall I ask Charles to dinner to-day?"

"As you please, my dear."

"Do you think I had better walk or ride this afternoon?"

"Whichever you prefer."

"There," said Bella, "I told you so. That is always the way. Papa dear, you used always to be firing guns at sea. Do, please, fire one in this house--just one--before I leave it, and make the very windows rattle."

"I beg your pardon, Bella; I never wasted powder at sea. If the convoy sailed well and steered right I never barked at them. You are a modest, sensible girl, and have always steered a good course. Why should I hoist a petticoat and play the small tyrant? Wait till I see you going to do something wrong or silly."

"Ah! then you would fire a gun, papa?"

"Ay, a broadside."

"Well, that is something," said Bella, as she closed the door softly.

"No, no; it amounts to just nothing," said Sir Charles; "for you never will do anything wrong or silly. I'll accommodate you. I have thought of a way. I shall give you some blank cards; you shall write on them, 'I think I should like to do so and so.' You shall be careless, and leave them about; I'll find them, and bluster, and say, 'I command you to do so and so, Bella Bassett'--the very thing on the card, you know."

Bella colored to the brow with pleasure and modesty. After a pause she said: "How sweet! The worst of it is, I should get my own way. Now what I want is to submit my will to yours. A gentle tyrant--that is what you must be to Bella Bassett. Oh, you sweet, sweet, for calling me that!"

These projects were interrupted by a servant announcing luncheon. This made Sir Charles look hastily at his watch, and he found it was past two o'clock.

"How time flies in this house!" said he. "I must go, dearest; I am behind my appointment already. What do you do this afternoon?"

"Whatever you please, my own."

"I could get away by four."

"Then I will stay at home for you."

He left her reluctantly, and she followed him to the head of the stairs, and hung over the balusters as if she would like to fly after him.

He turned at the street-door, saw that radiant and gentle face beaming after him, and they kissed hands to each other by one impulse, as if they were parting for ever so long.

He had gone scarcely half an hour when a letter, addressed to her, was left at the door by a private messenger.

"Any answer?" inquired the servant.

"No."

The letter was sent up, and delivered to her on a silver salver.

She opened it; it was a thing new to her in her young life--an anonymous letter.

"MISS BRUCE--I am almost a stranger to you, but I know your character from others, and cannot bear to see you abused. You are said to be about to marry Sir Charles Bassett. I think you can hardly be aware that he is connected with a lady of doubtful repute, called Somerset, and neither your beauty nor your virtue has prevailed to detach him from that connection.

"If, on engaging himself to you, he had abandoned her, I should not have said a word. But the truth is, he visits her constantly, and I blush to say that when he leaves you this day it will be to spend the afternoon at her house.

"I inclose you her address, and you can learn in ten minutes whether I am a slanderer or, what I wish to be,

"A FRIEND OF INJURED INNOCENCE."

SIR CHARLES was behind his time in Mayfair; but the lawyer and his clerk had not arrived, and Miss Somerset was not visible.

She appeared, however, at last, in a superb silk dress, the broad luster of which would have been beautiful, only the effect was broken and frittered away by six rows of gimp and fringe. But why blame her? This is a blunder in art as universal as it is amazing, when one considers the amount of apparent thought her sex devotes to dress. They might just as well score a fair plot of velvet turf with rows of box, or tattoo a blooming and downy cheek.

She held out her hand, like a man, and talked to Sir Charles on indifferent topics, till Mr. Oldfield arrived. She then retired into the background, and left the gentlemen to discuss the deed. When appealed to, she evaded direct replies, and put on languid and imperial indifference. When she signed, it was with the air of some princess bestowing a favor upon solicitation.

But the business concluded, she thawed all in a moment, and invited the gentlemen to luncheon with charming cordiality. Indeed, her genuine bonhomie after her affected indifference was rather comic. Everybody was content. Champagne flowed. The lady, with her good mother-wit, kept conversation going till the lawyer was nearly missing his next appointment. He hurried away; and Sir Charles only lingered, out of good-breeding, to bid Miss Somerset good-by. In the course of leave-taking he said he was sorry he left her with people about her of whom he had a bad opinion. "Those women have no more feeling for you than stones. When you lay in convulsions, your housekeeper looked on as philosophically as if you had been two kittens at play--you and Polly."

"I saw her."

"Indeed! You appeared hardly in a condition to see anything."

"I did, though, and heard the old wretch tell the young monkey to water my lilac dress. That was to get it for her Polly. She knew I'd never wear it afterward."

"Then why don't you turn her off?"

"Who'd take such a useless old hag, if I turned her off?"

"You carry a charity a long way."

"I carry everything. What's the use doing things by halves, good or bad?"

"Well, but that Polly! She is young enough to get her living elsewhere; and she is extremely disrespectful to you."

"That she is. If I wasn't a lady, I'd have given her a good hiding this very day for her cheek!"

"Then why not turn her off this very day for her cheek?"

"Well, I'll tell you, since you and I are parted forever. No, I don't like."

"Oh, come! No secrets between friends."

"Well, then, the old hag is--my mother."

"What?"

"And the young jade--is my sister."

"Good Heavens!"

"And the page--is my little brother."

"Ha, ha, ha!"

"What, you are not angry?"

"Angry? no. Ha, ha, ha!"

"See what a hornets' nest you have escaped from. My dear friend, those two women rob me through thick and thin. They steal my handkerchiefs, and my gloves, and my very linen. They drink my wine like fishes. They'd take the hair off my head, if it wasn't fast by the roots--for a wonder."

"Why not give them a ten-pound note and send them home?"

"They'd pocket the note, and blacken me in our village. That was why I had them up here. First time I went home, after running about with that little scamp, Vandeleur--do you know him?"

"I have not the honor."

"Then your luck beats mine. One thing, he is going to the dogs as fast as he can. Some day he'll come begging to me for a fiver. You mark my words now."

"Well, but you were saying--"

"Yes, I went off about Van. Polly says I've a mind like running water. Well, then, when I went home the first time--after Van, mother and Polly raised a virtuous howl. 'All right,' said I--for, of course, I know how much virtue there is under their skins. Virtue of the lower orders! Tell that to gentlefolks that don't know them. I do. I've been one of 'em--'I know all about that,' says I. 'You want to share the plunder, that is the sense of your virtuous cry.' So I had 'em up here; and then there was no more virtuous howling, but a deal of virtuous thieving, and modest drinking, and pure-minded selling of my street-door to the highest male bidder. And they will corrupt the boy; and if they do, I'll cuts their black hearts out with my riding-whip. But I suppose I must keep them on; they are my own flesh and blood; and if I was to be ill and dying, they'd do all they knew to keep me alive--for their own sakes. I'm their milch cow, these country innocents."

Sir Charles groaned aloud, and said, "My poor girl, you deserve a better fate than this. Marry some honest fellow, and cut the whole thing."

"I'll see about it. You try it first, and let us see how you like it."

And so they parted gayly.

In the hall, Polly intercepted him, all smiles. He looked at her, smiled in his sleeve, and gave her a handsome present. "If you please, sir," said she, "an old gentleman called for you."

"When?"

"About an hour ago. Leastways, he asked if Sir Charles Bassett was there. I said yes, but you wouldn't see no one."

"Who could it be? Why, surely you never told anybody I was to be here to-day?"

"La, no, sir! how could I?" said Polly, with a face of brass.

Sir Charles thought this very odd, and felt a little uneasy about it. All to Portman Square he puzzled over it; and at last he was driven to the conclusion that Miss Somerset had been weak enough to tell some person, male or female, of the coming interview, and so somebody had called there--doubtless to ask him a favor.

At five o'clock he reached Portman Square, and was about to enter, as a matter of course; but the footman stopped him. "I beg pardon, Sir Charles," said the man, looking pale and agitated; "but I have strict orders. My young lady is very ill."

"Ill! Let me go to her this instant."

"I daren't, Sir Charles, I daren't. I know you are a gentleman; pray don't lose me my place. You would never get to see her. We none of us know the rights, but there's something up. Sorry to say it, Sir Charles, but we have strict orders not to admit you. Haven't you the admiral's letter, sir?"

"No; what letter?"

"He has been after you, sir; and when he came back he sent Roger off to your house with a letter."

A cold chill began to run down Sir Charles Bassett. He hailed a passing hansom, and drove to his own house to get the admiral's letter; and as he went he asked himself, with chill misgivings, what on earth had happened.

What had happened shall be told the reader precisely but briefly. .

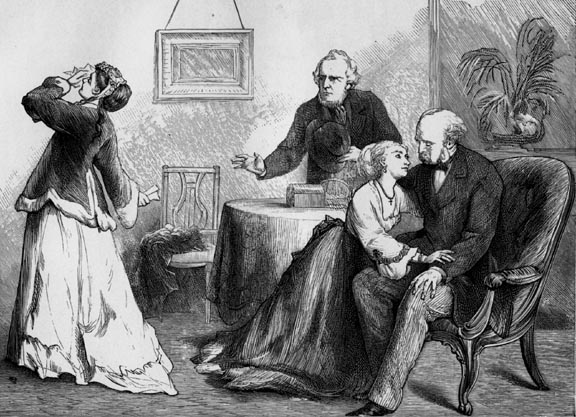

In the first place, Bella had opened the anonymous letter and read its contents, to which the reader is referred.

There are people who pretend to despise anonymous letters. Pure delusion! they know they ought to, and so fancy they do; but they don't. The absence of a signature gives weight, if the letter is ably written and seems true.

As for poor Bella Bruce, a dove's bosom is no more fit to rebuff a poisoned arrow than she was to combat that foulest and direst of all a miscreant's weapons, an anonymous letter. She, in her goodness and innocence, never dreamed that any person she did not know could possibly tell a lie to wound her. The letter fell on her like a cruel revelation from heaven.

The blow was so savage that, at first, it stunned her.

She sat pale and stupefied; but beneath the stupor were the rising throbs of coming agonies.

After that horrible stupor her anguish grew and grew, till it found vent in a miserable cry, rising, and rising, and rising, in agony.

"Mamma! mamma! mamma!"

Yes; her mother had been dead these three years, and her father sat in the next room; yet, in her anguish, she cried to her mother--a cry the which, if your mother had heard, she would have expected Bella's to come to her even from the grave.

Admiral Bruce heard this fearful cry--the living calling on the dead--and burst through the folding-doors in a moment, white as a ghost.

He found his daughter writhing on the sofa, ghastly, and grinding in her hand the cursed paper that had poisoned her young life.

"My child! my child!"

"Oh, papa! see! see!" And she tried to open the letter for him, but her hands trembled so she could not.

He kneeled down by her side, the stout old warrior, and read the letter, while she clung to him, moaning now, and quivering all over from head to foot.

"Why, there's no signature! The writer is a coward and, perhaps, a liar. Stop! he offers a test. I'll put him to it this minute."

He laid the moaning girl on the sofa, ordered his servants to admit nobody into the house, and drove at once to Mayfair.

He called at Miss Somerset's house, saw Polly, and questioned her.

He drove home again, and came into the drawing-room looking as he had been seen to look when fighting his ship; but his daughter had never seen him so. "My girl," said he, solemnly, "there's nothing for you to do but to be brave, and hide your grief as well as you can, for the man is unworthy of your love. That coward spoke the truth. He is there at this moment."

"Oh, papa! papa! let me die! The world is too wicked for me. Let me die!"

"Die for an unworthy object? For shame! Go to your own room, my girl, and pray to your God to help you, since your mother has left us. Oh, how I miss her now! Go and pray, and let no one else know what we suffer. Be your father's daughter. Fight and pray."

Poor Bella had no longer to complain that she was not commanded. She kissed him, and burst into a great passion of weeping; but he led her to the door, and she tottered to her own room, a blighted girl.

The sight of her was harrowing. Under its influence the admiral dashed off a letter to Sir Charles, calling him a villain, and inviting him to go to France and let an indignant father write scoundrel on his carcass.

But when he had written this his good sense and dignity prevailed over his fury; he burned the letter, and wrote another. This he sent by hand to Sir Charles's house, and ordered his servants--but that the reader knows.

Sir Charles found the admiral's letter in his letter-rack. It ran thus:

"SIR--We have learned your connection with a lady named Somerset, and I have ascertained that you went from my daughter to her house this very day.

"Miss Bruce and myself withdraw from all connection with you, and I must request you to attempt no communication with her of any kind. Such an attempt would be an additional insult.

"I am, sir, your obedient servant,

"JOHN URQUHART BRUCE."

At first Sir Charles Bassett was stunned by this blow. Then his mind resisted the admiral's severity, and he was indignant at being dismissed for so common an offense. This gave way to deep grief and shame at the thought of Bella and her lost esteem. But soon all other feelings merged for a time in fury at the heartless traitor who had destroyed his happiness, and had dashed the cup of innocent love from his very lips. Boiling over with mortification and rage, he drove at once to that traitor's house. Polly opened the door. He rushed past her, and burst into the dining-room, breathless, and white with passion.

He found Miss Somerset studying the deed by which he had made her independent for life. She started at his strange appearance, and instinctively put both hands flat upon the deed.

"You vile wretch!" cried Sir Charles. "You heartless monster! Enjoy your work." And he flung her the admiral's letter. But he did not wait while she read it; he heaped reproaches on her; and, for the first time in her life, she did not reply in kind.

"Are you mad?" she faltered. "What have I done?"

"You have told Admiral Bruce."

"That's false."

"You told him I was to be here to-day."

"Charles, I never did. Believe me."

"You did. Nobody knew it but you. He was here to-day at the very hour."

"May I never get up alive off this chair if I told a soul. Yes, our Polly. I'll ring for her."

"No, you will not. She is your sister. Do you think I'll take the word of such reptiles against the plain fact? You have parted my love and me--parted us on the very day I had made you independent for life. An innocent love was waiting to bless me, and an honest love was in your power, thanks to me, your kind, forgiving friend and benefactor. I have heaped kindness on you from the first moment I had the misfortune to know you. I connived at your infidelities--"

"Charles! Don't say that. I never was."

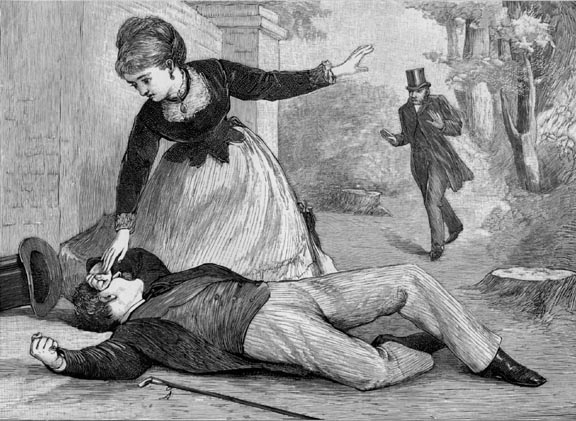

"I indulged your most expensive whims, and, instead of leaving you with a curse, as all the rest did that ever knew you, and as you deserve, I bought your consent to lead a respectable life, and be blessed with a virtuous love. You took the bribe, but robbed me of the blessing--viper! You have destroyed me, body and soul--monster! perhaps blighted her happiness as well; you she-devils hate an angel worse than Heaven hates you. But you shall suffer with us; not your heart, for you have none, but your pocket. You have broken faith with me, and sent all my happiness to hell; I'll send your deed to hell after it!" With this, he flung himself upon the deed, and was going to throw it into the fire. Now up to that moment she had been overpowered by this man's fury, whom she had never seen the least angry before; but when he laid hands on her property it acted like an electric shock. "No! no!" she screamed, and sprang at him like a wildcat.

Then ensued a violent and unseemly struggle all about the room; chairs were upset, and vases broken to pieces; and the man and woman dragged each other to and fro, one fighting for her property, as if it was her life, and the other for revenge.

Sir Charles, excited by fury, was stronger than himself, and at last shook off one of her hands for a moment, and threw the deed into the fire. She tried to break from him and save it, but he held her like iron.

Yet not for long. While he was holding her back, and she straining every nerve to get to the fire, he began to show sudden symptoms of distress. He gasped loudly, and cried, "Oh! oh! I'm choking!" and then his clutch relaxed. She tore herself from it, and, plunging forward, rescued the smoking parchment.

At that moment she heard a great stagger behind her, and a pitiful moan, and Sir Charles fell heavily, striking his head against the edge of the sofa. She looked round--as she knelt, and saw him, black in the face, rolling his eyeballs fearfully, while his teeth gnashed awfully, and a little jet of foam flew through his lips.

Then she shrieked with terror, and the blackened deed fell from her hands. At this moment Polly rushed into the room. She saw the fearful sight, and echoed her sister's scream. But they were neither of them women to lose their heads and beat the air with their hands. They got to him, and both of them fought hard with the unconscious sufferer, whose body, in a fresh convulsion, now bounded away from the sofa, and bade fair to batter itself against the ground.

They did all they could to hold him with one arm apiece, and to release his swelling throat with the other. Their nimble fingers whipped off his neck-tie in a moment; but the distended windpipe pressed so against the shirt-button they could not undo it. Then they seized the collar, and, pulling against each other, wrenched the shirt open so powerfully that the button flew into the air, and tinkled against a mirror a long way off.

A few more struggles, somewhat less violent, and then the face, from purple, began to whiten, the eyeballs fixed; the pulse went down; the man lay still.

"Oh, my God!" cried Rhoda Somerset. "He is dying! To the nearest doctor! There's one three doors off. No bonnet! It's life and death this moment. Fly!"

Polly obeyed, and Doctor Andrews was actually in the room within five minutes.

He looked grave, and kneeled down by the patient, and felt his pulse anxiously.

Miss Somerset sat down, and, being from the country, though she did not look it, began to weep bitterly, and rock herself in rustic fashion.

The doctor questioned her kindly, and she told him, between her sobs, how Sir Charles had been taken.

The doctor, however, instead of being alarmed by those frightful symptoms she related, took a more cheerful view directly. "Then do not alarm yourself unnecessarily," he said. "It was only an epileptic fit."

"Only!" sobbed Miss Somerset. "Oh, if you had seen him! And he lies like death."

"Yes," said Dr. Andrews; "a severe epileptic fit is really a terrible thing to look at; but it is not dangerous in proportion. Is he used to have them?"

"Oh, no, doctor--never had one before."

Here she was mistaken, I think.

"You must keep him quiet; and give him a moderate stimulant as soon as he can swallow comfortably; the quietest room in the house; and don't let him be hungry, night or day. Have food by his bedside, and watch him for a day or two. I'll come again this evening."

The doctor went to his dinner--tranquil.

Not so those he left. Miss Somerset resigned her own luxurious bedroom, and had the patient laid, just as he was, upon her bed. She sent the page out to her groom and ordered two loads of straw to be laid before the door; and she watched by the sufferer, with brandy and water by her side.

Sir Charles now might have seemed to be in a peaceful slumber, but for his eyes. They were open, and showed more white, and less pupil, than usual.

However, in time he began to sigh and move, and even mutter; and, gradually, some little color came back to his pale cheeks.

Then Miss Somerset had the good sense to draw back out of his sight, and order Polly to take her place by his side. Polly did so, and, some time afterward, at a fresh order, put a teaspoonful of brandy to his lips, which were still pale and even bluish.

The doctor returned, and brought his assistant. They put the patient to bed.

"His life is in no danger," said he. "I wish I was as sure about his reason."

At one o'clock in the morning, as Polly was snoring by the patient's bedside, a hand was laid on her shoulder. It was Rhoda.

"Go to bed, Polly: you are no use here."

"You'd be sleepy if you worked as hard as I do."

"Very likely," said Rhoda, with a gentleness that struck Polly as very singular. "Good-night."

Rhoda spent the night watching, and thinking harder than she had ever thought before.

Next morning, early, Polly came into the sick-room. There sat her sister watching the patient, out of sight.

"La, Rhoda! Have you sat there all night?"

"Yes. Don't speak so loud. Come here. You've set your heart on this lilac silk. I'll give it to you for your black merino."

"Not you, my lady; you are not so fond of mereeny, nor of me neither."

"I'm not a liar like you," said the other, becoming herself for a moment, "and what I say I'll do. You put out your merino for me in the dressing-room."

"All right," said Polly, joyfully.

"And bring me two buckets of water instead of one. I have never closed my eyes."

"Poor soul! and now you be going to sluice yourself all the same. Whatever you can see in cold water, to run after it so, I can't think. If I was to flood myself like you, it would soon float me to my long home."

"How do you know? You never gave it a trial. Come, no more chat. Give me my bath: and then you may wash yourself in a tea-cup if you like--only don't wash my spoons in the same water, for mercy's sake!"

Thus affectionately stimulated in her duties, Polly brought cold water galore, and laid out her new merino dress. In this sober suit, with plain linen collar and cuffs, the Somerset dressed herself, and resumed her watching by the bedside. She kept more than ever out of sight, for the patient was now beginning to mutter incoherently, yet in a way that showed his clouded faculties were dwelling on the calamity which had befallen him.

About noon the bell was rung sharply, and, on Polly entering, Rhoda called her to the window and showed her two female figures plodding down the street. "Look," said she. "Those are the only women I envy. Sisters of Charity. Run you after them, and take a good look at those beastly ugly caps: then come and tell me how to make one."

"Here's a go!" said Polly; but executed the commission promptly.

It needed no fashionable milliner to turn a yard of linen into one of those ugly caps, which are beautiful banners of Christian charity and womanly tenderness to the sick and suffering. The monster cap was made in an hour, and Miss Somerset put it on, and a thick veil, and then she no longer thought it necessary to sit out of the patient's sight.

The consequence was that, in the middle of his ramblings, he broke off and looked at her. The sister puzzled him. At last he called to her in French.

She made no reply.

"Je suis à l'hôpital, n'est ce pas bonne soeur?"

"I am English," said she, softly.

"ENGLISH!" said Sir Charles. "Then tell me, how did I come here? Where am I?"

"You had a fit, and the doctor ordered you to be kept quiet; and I am here to nurse you."

"A fit! Ay, I remember. That vile woman!"

"Don't think of her: give your mind to getting well: remember, there is somebody who would break her heart if you--"

"Oh, my poor Bella! my sweet, timid, modest, loving Bella!" He was so weakened that he cried like a child.

Miss Somerset rose, and laid her forehead sadly upon the window-sill.

"Why do I cry for her, like a great baby?" muttered Sir Charles. "She wouldn't cry for me. She has cast me off in a moment."

"Not she. It is her father's doing. Have a little patience. The whole thing shall be explained to them; and then she will soon soften the old man. 'It is not as if you were really to blame."

"No more I was. It is all that vile woman."

"Oh, don't! She is so sorry; she has taken it all to heart. She had once shammed a fit, on the very place; and when you had a real fit there--on the very spot--oh, it was so fearful--and lay like one dead, she saw God's finger, and it touched her hard heart. Don't say anything more against her just now. She is trying so hard to be good. And, besides, it is all a mistake: she never told that old admiral; she never breathed a word out of her own house. Her own people have betrayed her and you. She has made me promise two things: to find out who told the admiral, and--"

"Well?"

"The second thing I have to do-- Well, that is a secret between me and that unhappy woman. She is bad enough, but not so heartless as you think."

Sir Charles shook his head incredulously, but said no more; and soon after fell asleep.

In the evening he woke, and found the Sister watching.

She now turned her head away from him, and asked him quietly to describe Miss Bella Bruce to her.

He described her in minute and glowing terms. "But oh, Sister," said he, "it is not her beauty only, but the beauty of her mind. So gentle, so modest, so timid, so docile. She would never have had the heart to turn me off. But she will obey her father. She looked forward to obey me, sweet dove."

"Did she say so?"

"Yes, that is her dream of happiness, to obey."

The Sister still questioned him with averted head, and he told her what had passed between Bella and him the last time he saw her, and all their innocent plans of married happiness. He told her, with the tear in his eye, and she listened, with the tear in hers. "And then," said he, laying his hand on her shoulder, "is it not hard? I just went to Mayfair, not to please myself, but to do an act of justice--of more than justice; and then, for that, to have her door shut in my face. Only two hours between the height of happiness and the depth of misery."

The Sister said nothing, but she hid her face in her hands, and thought.

The next morning, by her order, Polly came into the room, and said, "You are to go home. The carriage is at the door." With this she retired, and Sir Charles's valet entered the room soon after to help him dress.

"Where am I, James?"

"Miss Somerset's house, Sir Charles."

"Then get me out of it directly."

"Yes, Sir Charles. The carriage is at the door."

"Who told you to come, James?"

"Miss Somerset, Sir Charles."

"That is odd."

"Yes, Sir Charles."

When he got home he found a sofa placed by a fire, with wraps and pillows; his cigar case laid out, and a bottle of salts, and also a small glass of old cognac, in case of faintness.

"Which of you had the gumption to do all this?"

"Miss Somerset, Sir Charles."

"What, has she been here?"

"Yes, Sir Charles."

"Curse her!"

"Yes, Sir Charles."

"LOVE LIES BLEEDING."

BELLA BRUCE was drinking the bitterest cup a young virgin soul can taste. Illusion gone--the wicked world revealed as it is, how unlike what she thought it was--love crushed in her, and not crushed out of her, as it might if she had been either proud or vain.

Frail men and women should see what a passionate but virtuous woman can suffer, when a revelation, of which they think but little, comes and blasts her young heart, and bids her dry up in a moment the deep well of her affection, since it flows for an unworthy object, and flows in vain. I tell you that the fair head severed from the chaste body is nothing to her compared with this. The fair body, pierced with heathen arrows, was nothing to her in the days of old compared with this.

In a word--for nowadays we can but amplify, and so enfeeble, what some old dead master of language, immortal though obscure, has said in words of granite--here

No fainting--no vehement weeping; but oh, such deep desolation; such weariness of life; such a pitiable restlessness. Appetite gone; the taste of food almost lost; sleep unwilling to come; and oh, the torture of waking--for at that horrible moment all rushed back at once, the joy that had been, the misery that was, the blank that was to come.