CHARLES DICKENS

TO

WILKIE COLLINS

Edited by

Laurence Hutton

WILLIAM WILKIE COLLINS was a man of five or six and twenty when he first met Charles Dickens, in 1851. He had spent two years in study in Italy; four years as an articled clerk to a city firm in the tea trade; he had been a student of law in Lincoln's Inn; he had written a biography of his father, William Collins, R. A., who was a painter of some repute; he had published his first novel, Antonina, and he had determined to devote himself thenceforth to a career of literature.

Charles Dickens at this period was nearly forty years of age. He had given to the world the immortal Pickwick, Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickleby, The Old Curiosity Shop, Barnaby Rudge, The American Notes, Martin Chuzzlewit, The Chimes, The Cricket on the Hearth, Dombey and Son, The Haunted Man, and David Copperfield; and he had but recently commenced the publication of the weekly journal called Household Words. He was the intimate of Thackeray, from whom he was then not yet estranged, of Carlyle, Leigh Hunt, Macaulay, Sydney Smith, Wilkie, Jerrold, Landor, Rogers, Longfellow, Washington Irving, Jeffrey, Turner, "Rugby" Arnold, Leech, Lemon, and their peers; and he was the recognized head of his guild in England. The friendship and recognition of such a man were of inestimable value to the younger writer; and the intimacy then begun, and cemented by the marriage of the daughter of Dickens to the brother of Collins ten years later, continued unbroken until Dickens died in 1870.

The correspondence between them was frequent and familiar. Some portions of it are to be found in The Letters of Charles Dickens, edited by his sister-in-law and his eldest daughter and first published in 1880 as a supplement to Forster's Life; but a large number of letters from Dickens to Collins were discovered after the death of Collins by his friend and literary executor, Mr. A. P. Watt, who obtained from Miss Hogarth, the only remaining executer of Dickens, permission to publish them. From these letters Miss Hogarth selected the following specimens as being quite as characteristic and fully as interesting as any she gave to the public in her own volume, and they have been printed here under her own supervision.

They not only show their writer as he was willing to show himself to the man whom he loved, but they give an excellent idea of his methods of collaboration with the man whom he had selected from all others as an active partner in certain of his creative works.

Why it is not possible to print herewith Collins's replies, Dickens himself fully explained in the following letter, which was written to Macready on the 1st of March, 1855, and which has already been printed by Miss Hogarth and Miss Dickens:

"Daily seeing improper uses made of confidential letters in the addressing of them to a public audience that has no business with them, I made, not long ago, a great fire in my field at Gad's Hill and burnt every letter I possessed. And now I destroy every letter I receive not on absolute business, and my mind is so far at ease."

That Macready should not have acted upon this hint and have destroyed this particular letter, with all the others which his friend at Gad's Hill had ever written to him, is proof enough of Macready's opinion of Dicken's charms as an epistolary correspondent. The reading world would have lost much if the biographers of Dickens, and the hundreds of men and women who were fortunate enough to have been his friends, had not appreciated the public as well as the private value of everything he put on paper, even in his private notes; and it is greatly to be regretted that he did not write letters to himself--like his own Mr. Toots--and preserve them all.

On the 10th of February 1851, Dickens sent a note to Mr. W. H. Wills, his associate in conducting Household Words, asking him to take the part of a servant in the comedy of Not so Bad as we Seem, written by Bulwer for the Guild of Literature and Art, and played for the first time at Devonshire House in the month of May of the same year by a company of very clever and very distinguished amateurs. " 'Mrs. Harris,' I says to her, 'be not alarmed; not reg'lar play-actors, hammertoors.' 'Thank 'Evens,' says Mrs. Harris, and bustiges into a flood of tears!"

Although Mr. Wills was actively interested in these entertainments, he does not seem ever to have appeared upon the stage; and Dickens was forced to seek a substitute, as the following letter will show. It was evidently given by its recipient, Augustus Egg, to its subject, and it was carefully cherished as long as Collins lived:

Devonshire Terrace,

Saturday Night, Eighth March, 1851.

MY DEAR EGG,-- I think you told me that Mr. Wilkie Collins would be glad to play any part in Bulwer's Comedy, and I think I told you that I considered him a very desirable recruit. There is a Valet, called (as I remember) Smart--a small part, but, what there is of it, decidedly good; he opens the play--which I should be delighted to assign to him, and in which he would have an opportunity of dressing your humble servant, frothing some chocolate with an obsolete milling-machine that must be revived for the purpose, arranging the room, and dispatching other similar "business," dear to actors. Will you undertake to ask him if I shall cast him in this part? If yes, I will call him to the reading on Wednesday; have the pleasure of leaving my card for him (say where), and beg him to favor us with his company at dinner on Wednesday evening. I knew his father well, and should be very glad to know him.

Write me a word in answer, and believe me ever,

Faithfully yours, CHARLES DICKENS

The first letter from Dickens to Collins which has been preserved was dated two months later, and is here subjoined. The Duke was the Duke of Devonshire, who entertained the party at supper after the first performance, and Mr. Ward was E. M. Ward, R. A., an early friend of Collins, who painted a portrait of Dickens in 1854.

No. 16, Wellington Street North, Strand,

Monday, Twelfth May, 1851

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- My only hesitation on the matter is this: I apprehend that the Duke in his great generosity intends to give a sort of supper to the whole party. I infer this from his so particularly desiring to know their number. Now, I have already given him the list; and he is so delicate that he would not even ask Landseer without first asking me. Under these circumstances, I feel the introduction of a stranger like Mr. Ward's brother--Mr. Ward and his wife being already on the list--a kind of difficulty; but I do not like to refuse compliance with any wish of my faithful and attached valet, whom I greatly esteem. I therefore merely mention this and send him the order.

I have been here all day, and am covered with Sawdust.

Faithfully yours always,

CHARLES DICKENS.

W. WILKIE COLLINS, Esquire.

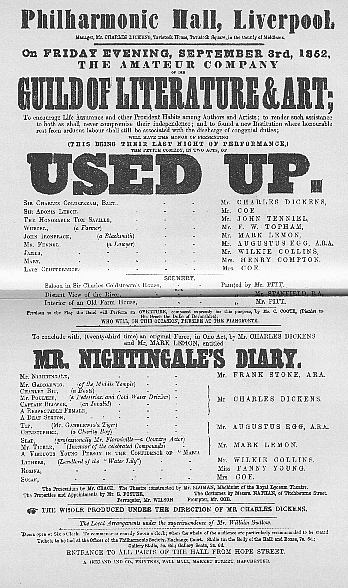

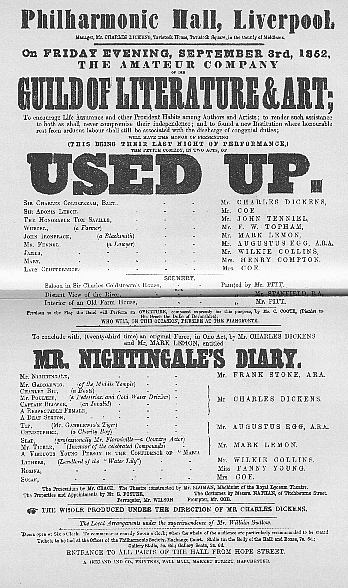

So much has been written and said by men like Forster and Hans Christian Andersen, as well as by Dickens, about the famous theatrical representations in which Dickens was so prominent, that no additional word, even from an eye-witness, can be of any interest here. But the editor of the present papers, who was taken, when almost a child, by a thoughtful father to see one of these performances, will never forget the impression made upon him by the acting of the protagonist on that occasion. The Bill of the Play--which is here reproduced in fac-simile--

contains many great names, which meant nothing then to the small boy who waited so patiently that night for Dickens to appear, and Dickens himself meant only David Copperfield. That small boy had never heard of Mr. John Tenniel, of Mr. Mark Lemon, of Mr. Augustus Egg, A. R. A., of Mr. Frank Stone, of Mr. Peter Cunningham, or of Mr. Wilkie Collins; but he had read and reread David Copperfield, and he looked upon it as a purely autobiographical and most delightful piece of work. He knew Steerforth and Traddles better than he knew many of his own school-mates; he hated Uriah Heep and the Murdstones more than he ever hated anybody else; he loved Dora and Agnes better than he ever expected, then, to love any woman but his own mother; he had gone sobbing to his little bed when he heard of David's mother's death, how "she was glad to lay her poor head on her stupid, cross, old Peggotty's arm; and she died like a child that had gone to sleep." Peggotty, with her cheeks and arms so hard and red that it was a wonder the birds didn't peck her in preference to apples, was more real to him than the Ann Hughes of his own nursery, whom no bird would he disposed to peck under any consideration: and although he had just made the grand tour for the first time, his only interest in the cathedral of St. Paul in London lay in the fact that it was pictured, with a pink dome, on the sliding lid of Peggotty's work-box. To see this grown-up David Copperfield in the flesh, doing all sorts of ridiculous things in the farce of Mr. Nightingale's Diary; to feel that, perhaps, he had a letter at that very moment in his pocket from the real Micawber; and that the actual Agnes was in the wings waiting to go home with him when the play was over, was to this particular little boy the greatest treat of his young life. And he has never ceased to thank the considerate father for the blessed memory of that wonderful night in Liverpool so many years ago.

That there existed a strong feeling of good-fellowship between Dickens and Collins from the very beginning of their acquaintance is indicated by the affectionate tone of the numerous letters which passed between them.

Lithers was the name of a character taken by Collins in one of the farcical afterpieces played by the company of amateurs, and Lord Wilmot was Dickens's part in Not so Bad as we Seem. Dickens was at work upon Bleak House when he wrote to Collins from Boulogne, in June, 1853; and when that story was finished in October, they started out, together with Augustus Egg, upon an excursion through parts of Switzerland and Italy; Egg being the Colonel alluded to as invited to "assist in scattering the family dinner" in April, 1854. The National Sparkler was one of the many names given to Dickens by himself. Basil, a Story of Modern Life, published in 1852, was Collins's first marked success as a writer of fiction, and Dickens alludes to it more than once in his letters to its author.

The occasional foot-notes signed "W. W. C." are in the handwriting of Collins. The parentheses in square brackets have been, on all occasions, added by the Editor.

Tavistock House,

Twenty-third December, 1852.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- I am suddenly laid by the heels in consequence of Wills having gone blind without any notice--I hope and believe from mere temporary inflammation. This obliges me to be at the office all day to-day, and to resume my attendance there to-morrow. But if you will come there to-morrow afternoon--say at about three o'clock--I think we may forage pleasantly for a dinner in the City, and then go and look at Christmas Eve in Whitechapel, which is always a curious thing.

The end of this letter (cut off for an autograph-hunter) simply mentioned the receipt of an odd letter from a namesake of mine inquiring for my address.--W. W. C.

Tavistock House,

Tuesday, January Eighteenth, 1853.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- If you should be disposed to revel in the glories of the eccentric British Drayma, on Saturday evening, I am the man to join in so great a movement. My money is to be heard of at the Bar of the Household Words at five o'clock on that afternoon.

Gin Punch is also to be heard of at the Family Arms, Tavistock, on Sunday next at five, when the National Sparkler will be prepared to give Lithers a bellyful if he means anything but Bounce.

I have been thinking of the Italian project, and reducing the time to two months--from the 20th October to the 20th December--see the way to a trip that shall really not exclude any foremost place, and be reasonable too. Details when we meet.

Ever faithfully, C. D.

Chateau des Moulineaux,

Rue Beaurepaire, Boulogne,

Friday, Twenty-fourth June, 1853.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- I hope you are as well as I am, and have as completely shaken off all your ailings. And I hope, too, that you are disposed for a long visit here. We are established in a doll's country house of many rooms in a delightful garden. If you have anything to do, this is the place to do it in. And if you have nothing to do, this is also the place to do it in to perfection.

You shall have a Pavilion room in the garden, with a delicious view, where you may write no end of Basils. You shall get up your Italian as I raise the fallen fortunes (at present sorely depressed) of mine. You shall live, with a delicate English graft upon the best French manner, and learn to get up early in the morning again. In short, you shall be thoroughly prepared, during the whole summer season, for those great travels that are to come off anon.

Do turn your thoughts this way, coming by South Eastern Tidal Train (there is a separate list for that train, the time changing every day as the tide varies), you come in five hours. No passport wanted. Mrs. Dickens and her sister send their kind regards, and beg me to say how glad they will be to see you.

W. WILKIE COLLINS, Esquire

Our united remembrances to your mother and brother.

Boulogne, Thirtieth June, 1853.

Thursday.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- I am very sorry indeed to hear so bad an account of your illness, and had no idea it had been so severe. I can't help writing (though most unnecessarily I hope) to say that you can't get well too soon; and that I warrant the pure air, regular hours, and perfect repose of this place to bring you round triumphantly. You have only, when you are sufficiently restored, to defy the D--octor and all his works, to write me a line naming your day and hour. My friend Lord Wilmot will then be found at the Custom House.

Ward's account of me was the true one. I was thoroughly disabled--in a week--and doubt if you would have known me. But I recovered with surprising quickness, positively insisting on coming here, against all advice but [Dr.] Elliotson's--and got to work next day but one as if nothing had happened.

And what was the matter with me? Sir--I find this reads like Dr. Johnson directly--Sir, it was an old, afflicted

once the torment of my childhood, in which I took cold.

Signature cut off for autograph-hunters. --W. C.

Tavistock House, Friday Night,

Twenty-fourth February, 1854.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- Sitting reading to-night, it comes into my head to say that if you look into Montaigne's Journey into Italy (not much known now, I think, except to readers), you will find some passages that would be curious for extract. They are very well translated into a sounding kind of old English in Hazlitt's translation of Montaigne.

If you are disengaged next Saturday, March the 4th, and it should be a fine day, what do you say to making it the occasion for our Rochester trip?

Faithfully yours always, C. D.

W. WILKIE COLLINS, Esquire

Tavistock House, Monday,

Twenty-fourth April, 1854.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- I met the Colonel at the Water Colors on Saturday, and asked him if he would assist in scattering the family dinner next Sunday at half past 5, as usual. Will you join us, Sir?

Beaucourt's house above the Moulineaux, on the top of the hill--free and windy--not so bijou-ish, but larger rooms, and possessing a back gate and a field, secured by the undersigned contracting party from the middle of June to the middle of October. I hope you will write the third volume of "that" book there.

[Chauncey Hare] Townshend coming to town on the 12th of May. Pray Heaven he may not have another choral birthday, and another frolicultural* cauliflower.

Ever faithfully, C. D.

*I think the word is a bold one. It is intended for floricultural.--C. D.

Tavistock House,

Sixth June, 1854.

MY DEAR COLLINS:

Form of trip appointment, in compliance with Act of

Parliament. Victoria, cap. 7, sec. 304

--------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------

Day, Thursday.

--------------------------------------------------------------

Hour, Quarter past 11 A.M.

--------------------------------------------------------------

Place, Dover Terminus, London Bridge

--------------------------------------------------------------

Destination, Tunbridge Wells.

--------------------------------------------------------------

Description of Railway Qualification, Return Ticket

--------------------------------------------------------------

(Signed) Charles Dickens

Entd.

--------------------------------------------------------------

Tavistock House,

Seventh June, 1854.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- Mark has got something in his foot--which is not Gout, of course, though it has a family likeness to that disorder--which he thinks will disable him to-morrow. Under these circumstances, and as this inclement season of summer has set in with so much severity, I think it may be best to postpone our expedition. Will you take a stroll on Hampstead Heath, and dine here on Sunday instead? And if yes, will you be here at 2?

Ever faithfully, C. D.

On the 22d of July, 1854, Dickens wrote to Miss Hogarth as quoted in the Letters:

"Neither you nor Catherine [Mrs. Dickens] did justice to Collins's book [Hide and Seek]. I think it far away the cleverest novel I have ever seen written by a new hand. It is in some respects masterly. Valentine Blyth is as original, and as well done, as anything can be. The scene where he shows his pictures is full of an admirable humor. Old Mat is admirably done. In short, I call it a very remarkable book, and have been very much surprised by its great merit."

Miss Hogarth is unable to explain the allusion to the "Cowell facts," in the letter of December 17, 1854. The "Mark" referred to in this and subsequent letters was Mark Lemon, editor of Punch.

Tavistock House,

Sunday, Seventeenth December, 1854

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- Many thanks for your note. As I rode home in the hansom, that Gravesend night, one or two doubts arose in my mind respecting the Cowell facts and before breakfast on the following morning I wrote to Mark, begging him to say nothing to Jerrold from me until I should have satisfied my mind. I am so sorry at heart for the working-people when they get into trouble, and have their wretched arena chalked out for them with such extraordinary complacency by small political economists, that I have a natural impulse upon me, almost always, to come to the rescue--even of people I detest, if I believe them to have been true to these poor men.

I am away to Reading to read the Carol, and to Sherborne, and, after Christmas Day, to Bradford, in Yorkshire. The thirtieth will conclude my public appearances for the present season, and then I hope we shall have some Christmas diversions here. I have got the children's play into shape, so far as the Text goes (it is an adaptation of Fortunio), but it has not been "on the stage" yet. Mark is going to do the Dragon--with a practicable head and tail.

Ever yours, C. D.

On the 6th of January, 1855, at Tavistock House, Dickens, Collins, and Lemon played in The Fairy Extravaganza of Fortunio and his Seven Gifted Sons, by Mr. Planché, the rest of the cast comprising the Dickens children and some of their juvenile friends. "They are all agog now," Dickens wrote a few days before, "about a great fairy play which is to come off here next Monday. The house is full of spangles, gas, Jews, theatrical tailors, and pantomime carpenters."

Tavistock House,

Christmas Eve, 1854.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- Here is a Part in Fortunio--dozen words--but great Pantomime opportunities--which requires a first-rate old stager to devour Property Loaves. Will you join the joke and do it? Gobbler, one of the seven gifted servants, is the Being "to let." There is an eligible opportunity of making up dreadfully greedy.

I am going to read the piece to the children next Tuesday, at half past 2. We shall rehearse it at the same hour every day in the following week--dress rehearsal on Saturday night, the 6th; night of performance, Monday, the 8th.

I am just come back from Reading and Sherborne, and go to Bradford on Wednesday morning, returning next day.

If you should chance to be disengaged to-day, here we are--Pork, with sage and inions, at half past 5.

Ever faithfully, C. D.

W. WILKIE COLLINS, Esquire

Tavistock House,

Sunday, Fourth March, 1855.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- I have to report another failure on the part of our friend "Williams" last night. He so confounded an enlightened British audience at the Standard Theatre on the subject of Antony and Cleopatra that I clearly saw them wondering, towards the end of the Fourth Act, when the play was going to begin.

A man much heavier than Mark (in the actual scale, I mean), and about twenty years older, played Cæsar. When he came on with a map of London--pretending it was a scroll and making believe to read it--and said, "He calls me Boy"--a howl of derision arose from the audience which you probably heard in the Dark, without knowing what occasioned it. All the smaller characters, having their speeches much upon their minds, came in and let them off without the slightest reference to cues. And Miss Glyn, in some entirely new conception of her art, "read" her part like a Patter song--several lines on end with the rapidity of Charles Mathews, and then one very long word. It was very brightly and creditably got up, but (as I have said) "Williams" did not carry the audience, and I don't think the Sixty Pounds a week will be got back by the Manager.

You will have the goodness to picture me to yourself--alone--in profound solitude--in an abyss of despair--ensconced in a small Managerial Private Box in the very centre of the House--frightfully sleepy (I had a dirty steak in the City first, and I think they must have put Laudanum into the Harvey's sauce), and played at, point-blank, by the entire strength of the company. The horrors in which I constantly woke up, and found myself detected, you will imagine. The gentle Glyn, on being called for, heaved her snowy bosom straight at me, and the box-keeper informed me that the Manager who brought her on would "have the honor of stepping round directly." I sneaked away in the most craven and dastardly manner, and made an utterly false representation that I was coming back again.

If you will give me one glass of hot gin-and-water on Thursday or Friday evening, I will come up about 8 ( )* o'clock with a cigar in my pocket and inspect the Hospital. I am afraid this relaxing weather will tell a little faintly on your medicine, but I hope you will soon begin to see land beyond the Hunterian Ocean.

I have been writing and planning and making notes over an immense number of little bits of paper--and I never can write legibly under such circumstances.

Always cordially yours, C. D.

W. WILKIE COLLINS, Esquire

*( ) Intended for "eight."--C. D.

Sister Rose, a story in four parts, by Collins, was printed in Household Words, in April and May, 1855. Mr. Pigott is Mr. Edward Pigott, an intimate friend of Collins, and the present "Licenser of Plays" in the Lord Chamberlain's office. He was in the cast of The Frozen Deep, produced by Dickens and Collins two years later.

Tavistock House,

Monday, Nineteenth March, 1855.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- I have read the two first portions of Sister Rose with the very greatest pleasure. An excellent story, charmingly written, and shewing everywhere an amount of pains and study in respect of the art of doing such things that I see mighty seldom.

If I be right in supposing that the brother and sister are concealing the husband's mother, then will you look at the closing scene of the second part again, and consider whether you cannot make the indication of that circumstance a little more obscure--or, at all events, a little less emphatic; as by Rose's only asking her brother once for leave to tell her husband, or some slight alteration of that kind? The best way I know of strengthening the interest and hitting this point would be the introduction or mention, in the first instance, of some one other person who might (in the reader's divided thoughts) be the concealed person, and of whom the husband might have a latent dislike or jealousy--as a friend of the brother's. But this might involve too great a change.

If, on the other hand, it be not the mother who is visited, then it is clear that you have altogether succeeded as it stands, and have entirely misled me.

How are you getting on? Shall you be up to a day at Ashford to-morrow week? I shall be able to frank you down and up the Railway on the solemn occasion. Mark (whose face is at present enormous) is going, and Wills will tell us the story of the Bo'sen, whose artful chaff, in that sparkling dialogue, played the Devil with T. Cooke.

Talking of which feat, I wish you could have seen your servant last Wednesday beleaguer the Literary Fund. They got so bothered and bewildered that I expected to see them all fade away under the table; and the outsiders laughed so irreverently whenever I poked up the chairman that it was quite a facetious business. Virtually, I consider the thing done. You may believe that I am not about to let go, and the effect has far and far exceeded my expectations already. Mark is full of the subject and will tell you all about it. . . .

What is Mr. Pigott's address? I want to leave a card for him.

Ever faithfully, C. D.

Tavistock House,

Saturday, Twenty-fourth March, 1855.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- I am charmed to hear of the great improvement, and really hope now that you are beginning to see land.

The train (an express one) leaves London Bridge Station on Tuesday at half past 11 in the forenoon. Fire and comfort are ordered to be in readiness at the Inn at Ashford. We shall have to return at half past 2 in the morning--getting to town before 5--but the interval between the Reading and the Mails will be spent by what would be called in a popular musical entertainment "the flick o' our ain firesides"--which reminds me to observe that I am dead sick of the Scottish tongue in all its moods and tenses.

You have guessed right! The best of it was that she [Mrs. Gaskell] wrote to Wills, saying she must particularly stipulate not to have her proofs touched, "even by Mr. Dickens." That immortal creature had gone over the proofs [North and South] with great pains--had of course taken out the stiflings--hard-plungings, lungeings, and other convulsions--and had also taken out her weakenings and damagings of her own effects. "Very well," said the gifted Man, "she shall have her own way. But after it's published shew her this Proof, and ask her to consider whether her story would have been the better or the worse for it."

When you see Millais, tell him that if he would like a quotation for his fireman picture there is a very suitable and appropriate one to be got from Gay's Trivia. . . .

Ever yours,

CHARLES DICKENS.

I dined with an old General yesterday, who went perfectly mad at dinner about the Times--exudations taking place from his mouth while he denied all its statements, that were partly foam, and partly turbot with white sauce. He persisted, likewise, in speaking of that Journal as "Him."

Tavistock House,

Wednesday, Fourth April, 1855.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- I have read the article in the Leader on Napoleon's reception in England with great pleasure and entire concurrence. I think it is forcible and just, and yet states the real case with great moderation. Not knowing of it, I had been speaking to its author on that very subject in the Pit of the Olympic on Saturday night.

And, by-the-bye, as the Devil would have it (for I assume that he is always up to something, and that everything is his fault--I being, as you know, evangelical), I mislaid your letter with Mr. Pigott's address in it, and "didn't like" to ask him for it. Do, like an amiable, corroded hermit, send me that piece of information again.

I hope the medical authorities will not--as I may say--cut your nose off to be revenged on your face. You might want it at some future time. It is but natural that the Doctor should be irritated by so much opposition--still, isn't the offending feature in some sort a man and a brother?

The Pantomine was amazingly good, and it really was a comfortable thing to see all conventional dignity so outrageously set at naught. It was astonishingly well done, and extremely funny. Not a man in it who wasn't quite as good as the Humbugs who pass their lives in doing nothing else. I observed at the Fund Dinner that the actors are in the same condition about it as they were when we played. Idiots!

May the Spring advance with rosy foot, and the voice of the Turtle be shortly heard in the land.

Ever faithfully, C. D.

Tavistock House,

Sunday, Fifteenth April, 1855.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- Hurrah!

I shall be charmed to see you once more in a Normal state, and propose Friday next for our meeting at the Garrick, at a quarter before 5. We will then proceed to the Ship and Turtle.

I fell foul of Wills yesterday, for that in "dealing with" the second part of your story [Sister Rose] he had not (in two places) "indoctrinated" the Printer with the change of name. He explained to me that on the whole, and calmly regarding all the facts from a politico-economical point of view, it was a more triumphant thing to have two mistakes than none--and, indeed, that, philosophically considered, this was rather the object and province of a periodical.

Faithfully always, C. D.

Collins was at this time a constant contributor to Household Words, and his After Dark (1856) and Dead Secret (1857) originally appeared in that periodical. The great success of Fortunio inspired Mr. Crummles, the Manager--a name given by Dickens to himself--to attempt the production of a more serious play, and led to the writing by Collins of The Light-house, a drama which was afterwards seen upon the public boards of the London Olympic. On May 20 Dickens wrote to Clarkson Stanfield:

"I have a little lark in contemplation, if you will help it to fly. Collins has done a melodrama (a regular old style melodrama), in which there is a very good notion. I am going to act in it, as an experiment, in the children's theatre here [Tavistock House]. I, Mark, Collins, Egg, and my daughter Mary, the whole dram. pers. . . . Now there is only one scene in the piece, and that, my tarry lad, is the inside of a light-house. Will you come and paint it?"

Nothing has been recorded concerning the acting of the author; but Carlyle, who was present as a first-nighter, compared Dickens's wild picturesqueness in the old light-house keeper to the famous figure in Nicholas Poussin's bacchanalian dance in the National Gallery. Mr. Stanfield's original sketch for the scene of the Eddystone Light-house, which hung in the hall at Gad's Hill until Dickens died, was afterwards sold for a thousand guineas.

The ticket referred to in the letter of June 24, 1855, was a card of admission to a meeting of "The Administrative Reform League," held in Drury Lane Theatre, at which Dickens made an effective speech. Colonel Waugh was at that time living in Campden House, Church Street, Kensington, a fine old mansion since destroyed by fire. It contained a private theatre, in which the Company of Amateurs gave several performances.

Tavistock House,

Friday, Eleventh May, 1855.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- I will read the play referring to the Light-house with great pleasure if you will send it to me--of course will at any time, with cordial readiness and unaffected interest, do any such thing. . . .

I hope to make Folkestone the country quarters for this Autumn. At the end of October I have an idea of removing the caravan to Paris for six months. I wish you would come over too, and take a Bedroom hard by us. It strikes me that a good deal might be done for Household Words on that side of the water.

But we shall have plenty of leisure to talk about this at Folkestone.

I have seen nothing of ---- since he disarranged the whole metropolitan supply of gas. I have a general idea that he must have been upside down ever since, in some corner--like the groom to whom the sultan's daughter was to have been sacrificed. He was indeed Great and Grand. I went about the streets all next day, laughing like a Pantomime mask. I never did see anything so ridiculous.

The restless condition in which I wander up and down my room with the first page of my new book [Little Dorrit] before me defies all description. I feel as if nothing would do me the least good but setting up a Balloon. It might be inflated in the garden in front--but I am afraid of its scarcely clearing those little houses.

Ever faithfully, C. D.

Tavistock House,

Thursday, Twenty-first May, 1855.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- Lemon assures me that the Parts and Prompt book are to arrive to-day. Why they have not been here two days I cannot for the life of me make out. In case they do come, there is a good deal in the way of clearing the ground that you and I may do before the first Rehearsal. Therefore, will you come and dine at 6 to-morrow (Friday) and give the evening to it?

Faithfully ever, C. D.

Tavistock House,

Saturday Morning, June Ninth, 1855.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- I have had a communication from Stanfield since we parted last night, to the effect that he must have the Stage entirely to himself and his men on Thursday Night. I therefore write round to all the company, to remind them that Monday is virtually our last Rehearsal, and that we shall probably have to do your Play twice on that precious occasion.

Ever heartily yours, C. D.

Tavistock House,

Sunday, Twenty-fourth June, 1855.

MY DEAR COLLINS.-- I am delighted that I have this one ticket to spare out of six that I got for Home. If you will be at the principal door in Brydges Street a little before a quarter to 7, and will there meet my people as they come up, and go in with them, you will find your place secured. The Secretary writes me that it is necessary to be early, to avoid calling attention to this fact, as other places are not secured.

I am rather flustered about the thing just now, not knowing their ways, or what kind of audience they are, or how they go on at all. But I'll try them, and the best can do no more.

I have broached a move Kensingtonwards, for changing their arrangements altogether--dropping the Farce--putting their piece second--and playing The Light-house (Original cast and Scenery) first. I don't know whether anything may come of it, but I thought it well to make a discreet point that way. This for the present entirely between ourselves.

Will you tell your brother, with my regards, that I write to Townshend by to-morrow morning's mail? I am not quite sure where he is.

Ever yours, C. D.

Tavistock House,

Sunday, Eighth July, 1855.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- I don't know whether you may have heard from [Benjamin] Webster, or whether the impression I derived from Mark's manner on Friday may be altogether correct. But it strongly occurred to me that Webster was going to decline the Play, and that he really has worried himself into a fear of playing Aaron.

Now, when I got this into my head--which was during the Rehearsal--I considered two things--firstly, how we could best put about the success of the piece more widely and extensively even than it has yet reached, and, secondly, how you could be best assured against a bad production of it hereafter, or no production of it. I thought I saw, immediately, that the point would be to have this representation noticed in the Newspapers. So I waited until the Rehearsal was over and we had profoundly astonished the family, and then asked Colonel Waugh what he thought of sending some cards for Tuesday to the papers. He highly approved, and yesterday morning directed Mitchell to send to all the morning papers, and to some of the weekly ones--a dozen in the whole.

I dined at Lord John's [Russell] yesterday (where Meyerbeer was, and said to me after dinner, "Ah, mon ami illustre! Que c'est noble de vous entendre parler d'haute voix morale, à la table d'un Ministre!"--for I gave them a little bit of truth about Sunday, that was like bringing a Sebastopol battery among the polite company)--I say, after this long parenthesis, I dined at Lord John's, and found great interest and talk about the Play, and about what everybody who had been here had said of it. And I was confirmed in my decision that the thing for you was the Invitation to the papers. Hence I write to tell you what I have done.

I dine at home at half past 5, if you are disengaged, and shall be at home all the evening.

Ever faithfully, C. D.

For the Christmas number of Household Words in 1855 Dickens and Collins wrote, together, The Holly Tree, Dickens contributing Myself, Boots, and The Bill according to the bibliography contained in Forster's Life.

Hotel des Bains, Boulogne,

Sunday, Fourteenth October, 1855.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- Behold me in our old quarters, which are as comfortable as usual. Crossed yesterday. Fine overhead, but heaving and surging sea. The Plorn [a nickname given to his youngest son, Edward Bulwer Lytton Dickens] wonderfully sick, but wonderfully good--making no complaint whatever--feeling the unreasonableness and hopelessness of the Ocean. . . .

The Ostler [in The Holly Tree] shall be yours, and I think the sketch involves an extremely good and startling idea. I am not, however, sure but that it trails off in the sudden disappearance of the woman without any result or explanation, and that some such thing may not be wanted for the purpose--unless her never being heard of any more could be so very strikingly described as to supply the place of other culmination to the story. Will you consider that point again?

I purpose being in town on the 13th of November. It is our Audit Day. Perhaps you will dine at the office at half past 5?

Kindest regards from all.

Ever faithfully yours,

CHARLES DICKENS.

W. WILKIE COLLINS, Esquire

Paris, 49 Avenue des Champs Elysées,

Wednesday, Twelfth December, 1855.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- . . . I leave here for town on Saturday, but shall have to start for Peterborough on Monday morning. If you are free on Wednesday (when I shall return from that reading), and will meet me at the Household Words office at half past 5, I shall be happy to start on any Haroun Alraschid expedition.

Think of my going down to Sheffield on Friday, to read there--in the bitter winter--with journey back to Paris before me.

I thought your Christmas Story [The Ostler] immensely improved in the working out. The botheration of that No. has been prodigious. The general matter was so disappointing, and so impossible to be fitted together or got into the frame, that after I had done the Guest and the Bill, and thought myself free for a little Dorrit again, I had to go back once more (feeling the thing too weak), and do the Boots. Look at said Boots; because I think it's an odd idea, and gets something of the effect of a Fairy Story out of the most unlikely materials. . . .

Every Frenchman who can write a begging letter writes one, and leaves it for this apartment. He first of all buys any literary composition printed in quarto on tea-paper with a limp cover, scrawls upon it "Hommage à Charles Dickens, l'illustre Romancier"--encloses the whole in a dirty envelope, reeking with tobacco smoke--and prowls, assassin-like, for days, in a big cloak and an enormous cachenez like a counterpane, about the scraper of an outer door.

Ever faithfully, C. D.

Reply as to Wednesday, in note to Tavistock House for receipt there on Sunday.

49 Champs Elysées,

Thirtieth January, 1856, Wednesday.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- I hope you are "out of the wood, and holloaing."

I purpose coming to town either on Monday or Tuesday night, and returning (if convenient to you), on the following Sunday or Monday. I will write to you as soon as I arrive, and arrange for our devoting an early evening (I should like Wednesday next) to letting our united observation with extended view "survey mankind from China to Peru." On second thoughts, shall we appoint Wednesday now? Unless I hear from you to the contrary, I will expect you at Household Words at 5 that day.

Ever faithfully (working hard), C. D.

49 Champs Elysées, Paris,

Tuesday, Twelfth February, 1856.

MY DEAR COLLINS.-- I am delighted to receive your letter--which is just come to hand--and heartily congratulate you upon it. I have no doubt you will soon appear. I would recommend you, unless the Boulogne Boat serves to a marvel, to come by the Calais route--the day mail. Because in the winter there are no special trains on that Boulogne line in France, and waiting at Boulogne is a bore. The Pavilion is all ready, and is a wonder. Upon my word, it is the snuggest oddity I ever saw--the lookout from it the most wonderful in the world. . . .

We had a pleasant trip, and the best dinner at the "Bang" [Hôtel des Bains], Boulogne, I ever sat down to.

So, looking out for your next letter "advising self" of your coming,

Ever faithfully, C. D.

49 Champs Elysées, Paris.

Sunday, Twenty--fourth February, 1856.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- The Post still coming in to-day without any intelligence from you, I am getting quite uneasy. From day to day I have hoped to hear of your recovery, and have forborne to write, lest I should unintentionally make the time seem longer to you. But I am now so very anxious to know how you are that I cannot hold my hand any longer. So pray let me know by return. And if you should unhappily be too unwell to write yourself, pray get your brother to represent you.

I cannot tell you how unfortunate I feel this to be, or how disconsolately I look at the uninhabited Pavilion.

Ever faithfully, C. D.

Dickens spent the winter of 1855-56, or the greater part of it, in Paris. On the 26th of March he wrote to Macready: "You will find us in the queerest of little rooms all alone, except that the son of Collins, the painter (who writes a good deal in Household Words) dines with us every day." Here they planned The Wreck of the Golden Mary, which appeared in Household Words the following Christmas, and here they conceived the idea of The Frozen Deep, a drama written by Collins for performance at Tavistock House.

The version of As You Like It which amused Dickens and Macready so much was by Georges Sand, who is, unquestionably, the "she" mentioned by Dickens as knowing "just nothing at all about it." It is strange that the fact that Madame Dudevant introduces Shakespeare as one of the characters in his own comedy did not strike Dickens as worthy of remark.

The Poole mentioned in the letter of April 13th, and later throughout the correspondence, was John Poole. the dramatist, whom Dickens helped in many ways, and who, at Dickens's urgent request, was placed on the Civil List as a pensioner in 1850. M. Forgues was at that time (1856) editor of the Revue des Deux Mondes, for whom Dickens, at Collins's request, wrote a fragment of autobiography.

Champs Elysées,

Sunday, April Thirteenth, 1856.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- We checked you off at the various points of your journey all day, but never dreamed of the half gale. You must have had an abominable passage with that convivial club. My soul sickens at the thought of it; and the smell seized hold of the bridge of my nose exactly half-way up, and won't let it go again.

Your portress duly appeared with the small account and your note. I paid her immediately, of course, and she departed rejoicing. The Pavilion looks very desolate, and nobody has taken it as yet. Macready left us at 7 yesterday morning, and I afterwards took a long country walk to get into train for work. It was a noble spring day, and the air most delightful. But I found the evening sufficiently dull, and indeed we all miss you very much. . . .

Macready went on Friday to the Rehearsal of Comme il vous plaira [As You Like It], which was produced last night. His account of it was absolutely stunning. The speech of the Seven Ages delivered as a light comedy joke; Jacques at the Court of the Reigning Duke instead of the banished one, and winding up the thing by marrying Celia! Everything as wide of Shakespeare as possible, and confirming my previous impression that she knew just nothing at all about it. She was to have been here on Friday evening, but had "la migraine" (of which I think you have heard before); but Regnier said, as to the piece, "La pièce. Il n'y a point de pièce," tapped his forehead with great violence, and threw whatever liquid came out into the air, as an offering to the offended gods. Girardin said, "Qu'il l'avait trouvé à la répétition très intéressante, très intéressante, très intéressante!"--and said nothing more the whole evening. I dine at another of his prodigious banquets to-morrow.

I am very anxious to know what your Doctor says. If he should fail to set you up by the 3d or 4th of May for me I shall consider him a Humbug. It occurs to me to mention that if you don't get settled in May, the Hogarths will then leave Tavistock House to me and Charley, and you know how easily and amply it can accommodate you. Pray don't forget that it is available for your quarters. There will be two or three large airy bedrooms with nobody to occupy them, and the range of the whole sheeted house besides. The Pavilion of the Moulineaux I shall, of course, reserve for your summer occupation and work. Talking of which latter, I am reminded to say that the Scotch Housekeeper is secured.

You know exactly where I am sitting, what I am seeing, what I am hearing, what is going on around me in every way. I have not a scrap of news, except that Poole, at the Français, complained bitterly to Macready of your humble servant's neglect, which, considering that he would unquestionably be in some remote English workhouse but for me, I think characteristic. Macready's reply to him appears to have been: "Er--really--er--no Poole:--er-- must excuse me--host--um--friend--er-- great affection--um-- cannot permit--er-- must therefore distinctly beg. . . ."

All unite in kindest regard and best wishes for your speedily coming all right again.

Ever faithfully,

CHARLES DICKENS.

I enclose a letter from Forgues. The book of the Light-house accompanies it, which I will bring with me.

P.P.S.-- According to a highly illegible note I have from Forgues, it would seem that I ought to send you the book with some idea of your sending it back to me to send to him. The little Lemons therefore shall bring the book with them.

When Dickens was in Paris he found that the feuilleton of the Moniteur contained daily a French version of Chuzzlewit, and he wrote to Forster on the 6th of January, 1856, "I have already told you that I have received a proposal from a responsible bookselling house here [Paris] for a complete edition, authorized by myself, of a French translation of all my books;" and on the 17th of April he wrote to the same correspondent, "On Monday I am going to dine with all my translators at Hachette's, the bookseller who has made the bargain for the entire edition."

Champs Elysées,

Tuesday, Twenty-second April, 1856

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- I have been quite taken aback by your account of your alarming seizure; and have only become reassured again, firstly, by the good-fortune of your having left here and got so near your doctor; secondly, by your hopefulness of now making head in the right direction. On the 3d or 4th I purpose being in town, and I need not say that I shall forthwith come to look after my old Patient.

On Sunday, to my infinite amazement, Townshend appeared. He has changed his plans, and is staying in Paris a week, before going to Town for a couple of months. He dined here on Sunday, and placidly ate and drank in the most vigorous manner, and mildly laid out a terrific perspective of projects for carrying me off to the Theatre every night. But in the morning he found himself with dawnings of Bronchitis, and is now luxuriously laid up in lavender at his Hotel--confining himself entirely to precious stones, chicken, and fragrant wines qualified with iced waters.

Last Friday I took Mrs. Dickens, Georgina, and Mary and Katey, to dine at the Trois frères. We then, sir, went off to the Français to see Comme il vous plaira--which is a kind of Theatrical Representation that I think might be got up, with great completeness, by the Patients in the asylum for Idiots. Dreariness is no word for it, vacancy is no word for it, gammon is no word for it, there is no word for it. Nobody has anything to do but to sit upon as many gray stones as he can. When Jacques had sat upon seventy-seven stones and forty-two roots of trees (which was at the end of the second act), we came away. He had by that time been made violent love to by Celia, had shewn himself in every phase of his existence to be utterly unknown to Shakespeare, had made the speech about the Seven Ages out of its right place, and apropos of nothing on earth, and had in all respects conducted himself like a brutalized, benighted, and besotted Beast.

A wonderful dinner at Girardin's last Monday, with only one new (but appropriate) feature in it. When we went into the drawing-room after the banquet, which had terminated in a flower-pot out of a ballet being set before every guest, piled to the brim with the ruddiest fresh strawberries, he asked me if I would come into another room (a chamber of no account--rather like the last Scene in Gustavus) and smoke a cigar. On my replying yes, he opened, with a key attached to his watch-chain, a species of mahogany cave, which appeared to me to extend under the Champs Elysées, and in which were piled about four hundred thousand inestimable and unattainable cigars, in bundles or bales of about a thousand each.

Yesterday I dined at the bookseller's with the body of Translators engaged on my new Edition--one of them, a lady, young and pretty. (I hope, by-the-bye, judging from the questions which they asked me and which I asked them, that it will be really well done.) Among them was an extremely amiable old Savant, who occasionally expressed himself in a foreign tongue which I supposed to be Russian (I thought he had something to do with the congress perhaps), but which my host told me, when I came away, was English! We wallowed in an odd sort of dinner which would have been splashy if it hadn't been too sticky. Salmon appeared late in the evening, and unforeseen creatures of the lobster species strayed in after the pudding. It was very hospitable and good-natured though, and we all got on in the friendliest way. Please to imagine me for three mortal hours incessantly holding forth to the translators, and, among other things, addressing them in a neat and appropriate (French) speech. I came home quite light-headed.

On Saturday night I paid three francs at the door of that place where we saw the wrestling, and went in, at 11 o'clock, to a Ball. Much the same as our own National Argyle Rooms. Some pretty faces, but all of two classes--wicked and coldly calculating, or haggard and wretched in their worn beauty. Among the latter was a woman of thirty or so, in an Indian shawl, who never stirred from a seat in a corner all the time I was there. Handsome, regardless, brooding, and yet with some nobler qualities in her forehead. I mean to walk about to-night and look for her. I didn't speak to her there, but I have a fancy that I should like to know more about her. Never shall, I suppose.

Franconi's I have been to again, of course. Nowhere else. I finished "that" No. as soon as Macready went away, and have done something for Household Words next week, called IProposals for a National Jest Book, that I take rather kindly to. The first blank page of Little Dorrit, No. 8, now eyes me on this desk with a pressing curiosity. It will get nothing out of me to-day, I distinctly perceive.

That swearing of the Academy Carpenters is the best thing of its kind I ever heard of. I suppose the oath to be administered by little Knight. It's my belief that the stout Porter, now no more, wouldn't have taken it. Our cook's going. Says she "ain't strong enough for BooLone." I don't know what there is particularly trying in that climate. The nice little Nurse, who goes into all manner of shops without knowing one word of French, took some lace to be mended the other day, and the Shopkeeper, impressed with the idea that she had come to sell it, would give her money; with which she returned weeping, believing it (until explanation ensued) to be the price of shame.

All send kindest regard.

Ever faithfully, C. D.

Ship Hotel, Dover,

Thirtieth April, 1856.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- Wills brought me your letter this morning, and I am very much interested in knowing what o'clock it is by the Watch with the brass tail to it. You know I am not in the habit of making professions, but I have so strong an interest in you and so true a regard for you that nothing can come amiss in the way of information as to your well-doing.

How I wish you were well now! For here I am in two of the most charming rooms (a third, a bedroom you could have occupied, close by), overlooking the sea in the gayest way. And here I shall be, for a change, till Saturday. And here we might have been, drinking confusion to Baronetcies, and resolving never to pluck a leaf from the Toady Tree, till this very small world shall have rolled us off! Never mind. All to come--in the fulness of the Arctic Seasons.

I take, as the people say in the comedies of eighty years ago, "hugely" to the idea you have suggested to Wills. But you mustn't do anything until you feel it a pleasure; from which sensation (and the disappearance of the East Wind until next winter) I shall date your coming round the corner with a great velocity.

On Saturday morning I shall be in town about 11, and will come on to Howland Street about 1. Many thanks for your bulletin academical, which I have despatched straightway to Ary Scheffer.

They were all blooming in Paris yesterday morning. I took the Plorn out in a cabrio--let the day before, and his observations on life in general were wonderful.

Ever yours, C. D.

On the 13th of July Dickens wrote to Collins from Boulogne as follows, concerning The Diary of Anne Rodway, by the latter, published in Household Words during that month: "I cannot tell you what a high opinion I have of Anne Rodway. . . . I read the first part at the office with strong admiration, and read the second on the railway coming back here. . . . My behavior before my fellow-passengers was weak in the extreme, for I cried as much as you could possibly desire. . . . I think it excellent, feel a personal pride and pleasure in it, which is a delightful sensation, and I know no one else who could have done it."

Boulogne,

Tuesday, Twenty-ninth July, 1856.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- I write you at once, in answer to yours received this morning, because there is a slight change in my London plans, necessitated by Townshend's intention of coming to the Pavilion here on the 5th or 6th, and hoping to have me pretty much at his disposal for a week or so.

Therefore, if Wills should purpose returning to London on Friday or on Saturday, I shall come up with him, and return here on the 4th or 5th of August. Will you hold yourself disengaged for next Sunday until you hear from me? I think I am very likely to be on the loose that day.

(Having done this morning, I am only waiting here for Wills, whom I don't like to despoil of his trip by going across now.)

On the 15th we shall, of course, delightedly expect you, and you will find your room in apple-pie order. I am charmed to hear you have discovered so good a notion for the play [The Frozen Deep]. Immense excitement is always in action here on the subject, and I don't think Mary and Katey will feel quite safe until you are shut up in the Pavilion on pen and ink.

I like that view of the picture controversy (what a World it is!) very much, and shall be glad and much assisted if you will tell me, by return, when you can have the copy ready, and about how long it will be. My reason is this: to facilitate poor Wills's getting a holiday. . . .

We are getting more than usual in advance; and if you can satisfy me on these points while I have Wills beside me, I can keep a No. open, and lead it off with that paper.

The château continues to be the best known, and the Cook is really special.

All send their kindest regard, and their welcome for the 15th on beforehand.

Ever faithfully, C. D.

The Frozen Deep was produced on the anniversary of the birth of the younger Charles Dickens, Twelfth night, 1857. Dickens, writing concerning it on the 17th of January, said "We have just been acting a new play of great merit, done in what I may call (modestly speaking of the getting up and not of the acting) an unprecedented way. I believe that anything so complete has never been seen. We had an act at the North Pole, where the slightest and greatest things the eye beheld were equally taken from the books of the polar voyagers. . . . It has been the talk of all London for these three weeks."

Mrs. W. H. Wills was a member of the dramatic company, and Mr. J. W. Francesco Berger undertook the musical part of the plays. Richard Wardour was the character assumed by Dickens.

Tavistock House,

Twelfth September, 1856.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- An admirable idea. It seems to me to supply and include everything the play wanted. But it is so very strong that I doubt whether the man can (without an anti-climax) be shewn to be rescued and alive until the last act. The struggle, the following him away, the great suspicion, and the suspended interest, in the second. The relief and joy of the discovery in the third.

Here, again, Mark's part seems to me to be suggested. An honest, bluff man, previously admiring and liking me--conceiving the terrible suspicion--watching its growth in his own mind--and gradually falling from me in the very generosity and manhood of his nature--would be engaging in itself, would be what he would do remarkably well; would give me capital things to do with him (and you know we go very well together), and would greatly strengthen the suspended interest aforesaid.

I throw this out with all deference, of course, to your internal view and preconception of the matter. Turn it how you will, the strength of the situation is prodigious; and if we don't bring the house down with it, I'm a--Tory (an illegible word which I mean for T-O-R-Y).

Hoping to see you to-night,

Ever cordially, C. D.

Tavistock House, Saturday Night,

Thirteenth September, 1856.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- Another idea I have been waiting to impart. I dare say you have anticipated it. Now, Mrs. Wills's second sight is clear as to the illustration of it, and greatly helps that suspended interest. Thus: "You ask me what I see of those lost Voyagers. I see the lamb in the grasp of the lion--your bonnie bird alone with the hawk. What do I see? I see you and all around you crying, Blood! The stain of his blood is upon you!" (C. D.)

Which would be right to a certain extent, and absolutely wrong as to the marrow of it.

Ever yours, C. D.

Tavistock House,

Thursday, Ninth October, 1856.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- I should like to shew you some cuts I have made in the second act (subject to authorial sanction, of course). They are mostly verbal, and all bring the Play closer together.

Also, I should like to know whether it is likely that you will want to alter anything in these first two acts. If not, here are Charley, Mark, and I, all ready to write, and we may get a fair copy out of hand. From said fair copy all my people will write out their own parts.

I dine at home to-day, but not to-morrow. On Saturday, and Sunday likewise, I dine at home. We must perpetually "put ourselves in communication with the view of dealing with it"--as Wills says--the moment you have done. How do you get on? And will you come at 6 to-day--or when?

I am more sure than ever of the effect.

Ever faithfully, C. D.

Tavistock House,

Fifteenth October, 1856.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- Will you read Turning the Tables (in my old Prompt-book) enclosed, and let me know whether you dare to play Edgar de Courcy? There is very good business in it with Humphreys (Mark). My great difficulty is Patty Larkins.

Send me back the book when you answer.

Ever faithfully, C. D.

P.P.S.-- Here is Animal Magnetism to read, too. Will you get another copy for yourself at some theatrical shop? We play it in two acts.

Tavistock House,

Sunday Night, Twenty-sixth October, 1856.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- Will you tell Pigott of the Rehearsal arrangements when that Ancient Mariner turns up?

Will you dine at our H. W. [Household Words] Audit dinner, on Tuesday, the 4th of November, at half past 5?

Will you come and see the ladies, in the rough, next Thursday at half past 7?

Though mayhap you may come here before, for you will be glad to know that Stanfield arrived from Hollyhead at Midnight last night, and sent a Dispatch down here the first thing this morning, proposing to fall to, to-morrow. I have appointed him to be here at from 3 to half past to-morrow (Monday) afternoon to hear the Play; to dine at half past 5, and to go into the Theatre after dinner and settle his whole plans for the Carpenters. If you can come at the first of these times, or the second, or the third, it will be well. I have had an interview with the Authors, and printed them. I begin with the Merry Berger to-morrow night. I have found a very good farce (with character parts for all) in lieu of Turning the Tables. On the whole, have not been idle.

Ever faithfully, C. D.

Took twenty miles to-day, and got up all Richard's words [Richard Wardour], to the great terror of Finchley, Neasdon, Willesden, and the adjacent country.

Tavistock House,

Saturday Evening, First November, 1856.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- Forster came here yesterday afternoon to ask me if he might read the Play, and I lent it to him. This afternoon I got the enclosed from him (which please to read at this point). You know that I don't agree with him as to the Nurse. . . . But I think his suggestion that the going away of the women might be suggested at the close of the First act as a preparation for the last an excellent one. Will you think of it? By an alteration that we could make in a quarter of an hour it might be done; and, moreover--this suggestion upon a suggestion arises in my mind--it might be made the Nurse's position in the Play that her blood-red Second Sight is the first occasion of their going away at all. (Forster does not clearly understand the circumstances of their going; but never mind that).

His notion that Clara tells too much has been strong in my mind since I first got that act in Rehearsal. But, doubtful whether it might not unconsciously arise in me from a paternal interest in my own part, I had, as yet, said nothing about it--the rather as I had not yet seen the Second act on the stage.

Standfield wants to cancel the chair altogether, and to substitute a piece of rock on the ground, composing with the Cavern. That, I take it, is clearly an improvement. He has a happy idea of painting the ship which is to take them back, ready for sailing, on the sea.

Nothing could induce [William] Telbin yesterday to explain what he was going to do before Stanfield; and nothing would induce Stanfield to explain what he was going to do before Telbin. But they had every inch and curve and line in that bow accurately measured by the carpenters, and each requested to have a drawing of the whole made to scale. Then each said that he would make his model in card-board, and see what I "thought of it." I have no doubt the thing will be as well done as it can be.

Will you dine with us at 5 on Monday before Rehearsal? We can then talk over Forster's points. If you are disengaged on Wednesday, shall we breathe some fresh air in dilution of Tuesday's "alcohol," and walk through the fallen leaves in Cobham Park? I can then explain how I think you can get your division of the Christmas No. [Wreck of the Golden Mary] very originally and naturally. It came into my head to-day.

Ever faithfully, C. D.

P.S.-- I re-open this to say that I find from Wills that next Tuesday being the Audit Day at all is his mistake. It is Tuesday week. Therefore, if Tuesday is a fine day, shall we go out then?

Tavistock House

Friday, Fourteenth November, 1856.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- I could not send you the books before I went out this morning for a 12-miler, the collection being curiously spare in pick-up cases, and it being a work of time to find them.

Will you exchange proofs of the Captain [first part of The Wreck of the Golden Mary] with me? The proofs you have have markings of mine upon them which will be useful to me in correcting. You can bring me those when you come to-night.

Ever faithfully, C. D.

Tavistock House

Tuesday Evening, Sixteenth December, 1856.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- I send round to ascertain that you are all right. Not that I have any misgiving on the subject, for when I shook hands with you last night you were as cool and comfortable as an unlucky Dog could be.

All progressing satisfactorily. Telbin painting on the Stage. Carpenters knocking down the Drawing-room.

We are obliged to do Animal Magnetism on Thursday evening at 8. If you are strong enough to come, I know you will; if you are not, I know you won't.

Ever cordially, C. D.

Tavistock House,

Saturday, Tenth January, 1857.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- On second thoughts I am afraid of wasting the spirits of the company by calling the Dance at 6 on Monday. Therefore I abandon that intention. I hope we may get it right by speaking to one another in the Dressing-room.

On Play Days (only two more--how they fly!) Mark and I dine at 3, off steak and stout, at the Cock, in Fleet Street. If you should be disposed to join us, then and there you'll find us.

Ever cordially, C. D.

The MS. of The Frozen Deep was sold at auction in London in the summer of 1890 for three hundred guineas. Collins had added four pages of Introduction and a copy of the printed bill of the performance which was given in Manchester in August, 1857, for the benefit of the family of Douglas Jerrold, who had lately passed away. In the Manchester cast were Egg, Lemon, Shirley Brooks, Charles and Wilkie Collins, and Charles Dickens. In this Introduction Collins said: "Mr. Dickens himself played the principal part, and played it with a truth, vigor, and pathos never to be forgotten by those who were fortunate enough to witness it. . . . At Manchester this play was twice performed; on the second evening before three thousand people. This was, I think, the finest of all its representations. The extraordinary intelligence and enthusiasm of the great audience stimulated us all to do our best. Dickens surpassed himself. He literally electrified the audience." Collins rewrote the play and read it in Boston in the spring of 1874 as "a Special Farewell" to America, prefacing it with a short speech, in which he said that he understood it had already been produced at a Boston theatre (although then never printed) without his knowledge, and, of course, without his consent.

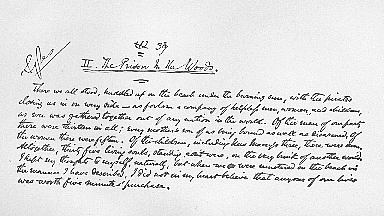

Dicken's took possession of Gad's Hill Place in the month of June, 1857. In September he visited the north of England with Collins, where Collins sprained one of his ankles severely, and where and when they concocted and began The Lazy Tour of Two Idle Apprentices--contributed jointly to Household Words in October. After their return they wrote, together, for the Christmas number of the same periodical, The Perils of Certain English Prisoners, and Their Treasure in Women, Children, Silver, and Jewels, the manuscript of which was sold in 1890 for two hundred pounds. It is one of the few pieces of the Dickens MSS. not bequeathed by Forster to the English nation. Of this Dickens wrote Chapters I. and III.; Collins, Chapter II., a fragment of which is here reproduced in fac-simile,

while the copy of each is crowded with many notes and corrections by both hands. The original sketch for the story was written by Collins, and contains hints and suggestions by the head of the literary copartnership, who also wrote the title-page, to which Collins added a few explanatory notes. On the 6th of February, 1858, Dickens sent the following note:

MY DEAR WILKIE,-- Thinking it may one day be interesting to you--say when you are weak in both feet, and when I and Doncaster are quiet, and the great race is over--to possess this little memorial of our joint Christmas work, I have put it together for you, and now send it on its coming home from the Binder. Faithfully yours,

CHARLES DICKENS.

Tavistock House,

Monday, Nineteenth January, 1857.

MY DEAR COLLINS.-- Will you come and dine here next Sunday at 5?

There is no one coming but a poor little Scotchman, domiciled in America--a musical composer and singer--who brought me a letter yesterday from New York, and quite moved me by his simple tale of loneliness. He is ----, softened by trouble, with all the starch out of his collar, and all the money out of his Bank.

O reaction, reaction!

Ever faithfully, C. D.

Tavistock House,

Fourteenth February, 1857.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- Will you come and dine at the office on Thursday at half past 5? We will then discuss the Brighton or other trip possibilities. I am tugging at my Oar too--should like a change--find the Galley a little heavy--must stick to it--am generally in a collinsion state.

Ever faithfully, C. D.

Tavistock House,

Wednesday, Fourth March, 1857.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- I cannot tell you what pleasure I had in the receipt of your letter yesterday evening, or how much good it did me in the depression consequent upon an exciting and exhausting day's work. I immediately arose (like the desponding Princes in the Arabian Nights, when the old woman--Procuress evidently, and probably of French extraction--comes to whisper about the Princesses they love) and washed my face and went out; and my face has been shining ever since.

Ellis [proprietor of the Bedford Hotel at Brighton] responds to my letter that rooms shall be ready! There is a train at 12 which appears to me to be the train for the distinguished visitors. If you will call for me in a cab at about 20 minutes past 11, my hand will be on the latch of the door.

I have got a book to take down with me of which I have not read a line, but which I have been saving up to get a pull at it in the nature of a draught--The Dead Secret--by a Fellow Student.

Plornish has broken ground with a Joke which I consider equal to Sydney Smith.

Ever faithfully,

CHARLES DICKENS.

Tavistock House,

Monday Evening, Eleventh May, 1857.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- I am very sorry that we shall not have you to-morrow. Think you would get on better if you were to come, after all.

Yes, sir; thank God, I have finished! [Little Dorrit]. On Sunday last I wrote the two little words of three letters each.

Any mad proposal you please will find a wildly insane response in

Yours ever, C. D.

We shall have to arrange about Tuesday at Gad's Hill. You remember the engagement?

Tavistock House,

Friday Evening Twenty-second May, 1857.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- Hooray!!

From our lofty heights let us look down on the toiling masses with mild complacency--with gentle pity--with dove-eyed benignity.

To-morrow I am bound to Forster; on Sunday to solemn Chief Justice's, in remote fastnesses beyond Norwood; on Monday to Geographical Societies dining to cheer on Lady Franklin's Expedition; on Tuesday to Procter's; on Wednesday, sir--on Wednesday--if the mind can devise anything sufficiently in the style of sybarite Rome in the days of its culminating voluptuousness, I am your man.

Shall we appoint to meet at the Household Words office at half past 5? I have an appointment with Russel [W. H.] at 3 that afternoon, which may, but which I don't think will, detain me a few minutes after my time. In that unlikely case, wait for me at the office?

If you can think of any tremendous way of passing the night, in the mean time, do. I don't care what it is. I give (for that night only) restraint to the Winds!

I am very much excited by what you tell me of Mr. F's aunt.* I already look upon her as mine. Will you bring her with you?

Wills tells me that he thinks the principles of story-writing are scarcely understood in this age and Empire.

Ever faithfully, C. D.

[*A picture by an artist named Gale, of that character in Little Dorrit, and bought by Charles Dickens through Collins.]

No. 16, Wellington Street, North, Strand,

First June (Monday), 1857.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- In consequence of bedevilments at Gad's Hill, arising from the luggage wandering over the face of the earth, I shall have to pass to-morrow behind a hedge, attired in leaves from my own fig-tree. Will you therefore consider out appointment to stand for next day--Wednesday?

When last heard of the family itself (including the birds and the goldfinch on his perch) had been swept away from the stupefied John by a crowd of Whitsun holiday-makers, and had gone (without tickets) somewhere down into Sussex. A desperate calmness has fallen upon me. I don't care.

Faithfully ever, C. D.

H. W. Office,

Sixteenth June, 1857.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- What an unlucky fellow you are! What a foot you have for putting into anything!

I write this to Harley Place, having been unable to write yesterday. I must be in town on Thursday, and will come up to you. I will try to come at about 12.

Mrs. Wills's lameness makes a new Esther the first thing wanted. You once said you knew a lady who could and would have done it. Is that lady producible?

Ever faithfully, C. D.

Tavistock House,

Friday Night, Twenty-sixth June, 1857.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- I am so sensible of that First Act's requiring--for the old hands--so much care in a less feverish atmosphere than the Theatre, that I must propose Rehearsals of the Ladies here (our house is stripped, and has plenty of room), on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday. The hour must rest principally with Mrs. Dickinson, but I should like it best in the evening--say it 8. However, my time is the Play's. There is a great deal at stake, and it must be well done. Will you see Mrs. Dickinson between this and Monday's rehearsal, and consult her convenience on the point?

I shall be at the Gallery during the greater part of to-morrow, and shall dine at the Garrick at 6, before going to the Concert.

Ever faithfully, C. D.

Tavistock House,

Sunday Morning, Second August, 1857.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- I write this on my way back to Gad's Hill from Manchester.

As our sum is not made up, and as I had urgent Deputation and so forth from Manchester Magnates at the reading on Friday night, I have arranged to act the Frozen Deep in the Free Trade Hall, on Friday and Saturday nights, the 21st and 22d. It is an immense place, and we shall be obliged to have actresses--though I have written to our friend, Mrs. Dickinson, to say that I don't fear her, if she likes to play with them. (I am already trying to get the best who have been on the stage.)

Whether Charley can play his part or not, I will tell him to let you know directly.

I had a letter from the Olympic the other day, begging me to go to a rehearsal. I have appointed next Friday, if agreeable and convenient. In haste,

Ever faithfully, C. D.

Garrick Club

Monday Evening, Seventeenth August, 1857.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- Fred Evans's grandmother being evidently on the point of Death, no Evans is available (as I learn on coming to town to-night) for Manchester. This leaves to be supplied Easel and Bateson. I immediately think of your brother Charles and Luard. If it had been a purely managerial and not a personal case, I should have proposed to Luard to do one of the parts and to your brother to do the other. But I think it right that Charles Collins should first select for himself. Now, will you, before you come to the Rehearsal to-morrow, arrange with him whether he will play one--which one--or both; and if he leaves one, will you call on Luard as you come down and offer that one to him?

I write at Express pace, but you will understand all I mean.

Ever faithfully, C. D.

Tavistock House

Saturday, Twenty-ninth August, 1857.

MY DEAR COLLINS,-- Partly in the grim despair and restlessness of this subsidence from excitement, and partly for the sake of Household Words, I want to cast about whether you and I can go anywhere--take any tour--see anything--whereon we could write something together. Have you an idea tending to any place in the world? Will you rattle your head and see if there is any pebble in it which we could wander away and play at marbles with? We want something for Household Words, and I want to escape from myself. For, when I do start up and stare myself seedily in the face, as happens to be my case at present, my blankness is inconceivable--indescribable--my misery amazing.

I shall be in town on Monday. Shall we talk then? Shall we talk at Gad's Hill? What shall we do? As I close this I am on my way back by train.

Ever faithfully, C. D.

Dickens devoted himself for many months during the year 1858 to public readings in the provinces of Great Britain.

Tavistock House,

Tavistock Square, London, W. C.,

Tuesday night, Twenty-fifth May, 1858.

MY DEAR WILKIE,-- A thousand thanks for your kind letter. I always feel your friendship very much, and prize it in proportion to the true affection I have for you.

Your letter comes to me only to-night. Can you come round to me in the morning (Wednesday) before 12? I can then tell you all in lieu of writing. It is rather a long story--over, I hope, now.